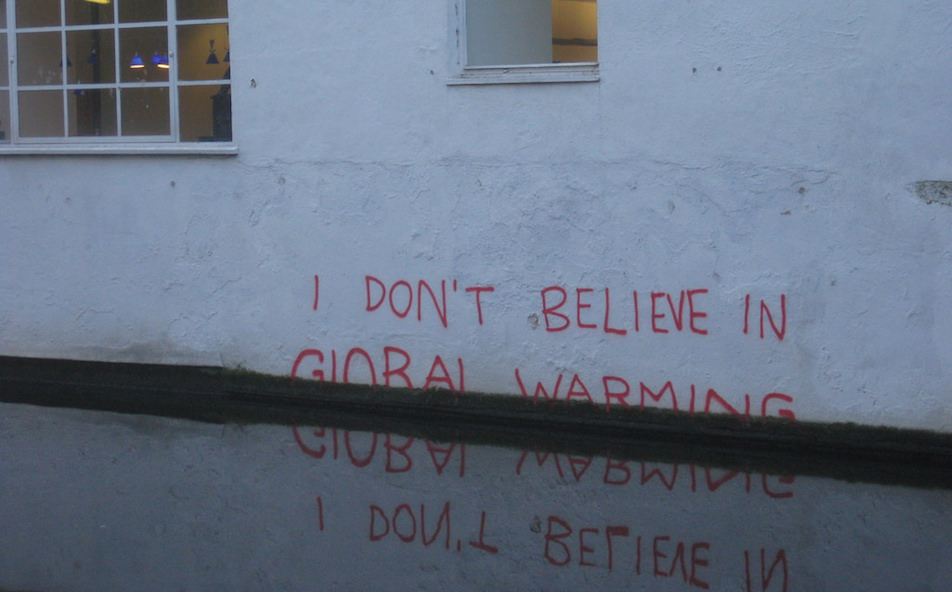

An art installation beside London’s Regent’s Canal by the British street artist Banksy offers his comment on climate-change denial, focusing on the sea-level rise that scientists say global warming is causing.

By Joseph A. Davis

Texas Climate News

Donald J. Trump’s surprise election to the presidency of the United States is a fact. It’s also a fact that he denies manmade climate change and wants to boost climate-disrupting fossil fuels. Now what?

In the energy and climate arena, the consequences will be huuuu… – er, enormous – even if they are still incompletely known. Some green pundits predict planetary disaster. Predicting anything, when it comes to Trump, can be a fool’s errand. But some writers – at least the ones who write horoscopes and Chinese fortune cookies — offer predictions that will come true no matter what.

Sure, the presidential foot will be lifted from the climate-action pedal and applied to the brake. But if we are already going too fast on a slippery road toward catastrophic climate change, it may not make much difference.

Example: President Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) and the Texas-led lawsuits against it. This showpiece regulatory effort to move electric power plants away from burning coal has inspired passionate opposition from a Koch-funded coalition of largely GOP states. But many states, even states in court opposing the CPP, are actually well on their way to the lower emissions of climate-warming carbon dioxide (the principal human-produced greenhouse gas) that it seeks. If Trump (or a court) were to tear up the CPP, the trend away from coal in the U.S. electric-utility fuel mix would likely continue. The main reasons: the low price of natural gas and falling price of clean renewables.

Trump’s campaign has promised to kill the CPP. But technically, it may not be possible to do this in the first 100 days of his administration, as bragged. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, when the executive rescinds a final rule, that is officially a rulemaking — which takes time, years sometimes. Eventually, one way or another, if he wants to, and if he goes through some time-consuming hurdles, and if nobody stops him in court, Trump could indeed kill the CPP.

Killing coal

But it is not the CPP that is taking away the Appalachian coal jobs Trump has promised to restore. It is the low price of natural gas, automation, de-unionization, and the movement of the market to Wyoming, where coal is cheaper to mine and lower in sulfur. Even as president, Trump is pretty powerless to raise the price of gas, which is increasingly replacing coal in the generation of electricity. Ironically, his fire-sale drill-baby-drill philosophy is only likely to hurt coal miners by driving the price of gas further downward.

Another example: Trump has promised to “cancel” the Paris Agreement to control climate change. Of course, it is not in one single nation’s power to “cancel” an international agreement signed by 195 countries. All a single nation can do is to withdraw from the agreement, leaving other nations to do what they will. After Trump’s election, nations said they would push ahead. But U.S. withdrawal would still harm the agreement, and harm progress toward reducing greenhouse emissions.

Now that the United States has actually “ratified” the Paris Agreement, formally getting out of it becomes a bit harder and more time-consuming. Article 28 of the Agreement says that once a country ratifies it, it can not withdraw until three years after the Agreement has taken force (November 4, 2016), and that the withdrawal will not take effect until a year after that. That is almost four years from now – by which time Trump could conceivably be on his way out of office. (According to one recent news report, however, members of Trump’s transition team are looking for possible ways to get out of the Paris pact much more quickly.)

Those are technicalities. Right now, nations voluntarily set their own emissions-reduction goals under the Paris agreement and there is no mechanism to enforce them anyway. The U.S. under Trump could simply stop trying. If Trump stops trying, would the U.S. still meet its stated target of a 26-28 percent reduction in greenhouse emissions below 2005 levels by 2025? It might well, or might come close.

Still, the doomsayers may be right about the consequences of Trump’s election. Scientists say more climate action, not less, is needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s current, modest goal of limiting manmade warming to 2 degrees C above pre-industrial levels – much less the more ambitious 1.5-degree C goal that many experts say is needed to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. And if the U.S. dropped out, the loss of strong U.S. leadership could leave future talks aimed at revisions to strengthen the agreement rudderless, and put China in a leadership role by default.

With his hands on the levers of power, Trump could do many other things with just his executive authority that would impact energy industries and climate. Areas where he (or “independent” commissions he appoints) could act without any legislative changes include:

- Increasing coal leasing on federal lands

- Increasing onshore oil and gas leasing on federal lands

- Increasing offshore oil and gas leasing

- Full-ahead permitting of oil and gas pipelines

- Full-ahead permitting of oil, coal, and liquefied natural gas export terminals

- Loosening emission restrictions on oil, gas, and petrochemical facilities

- Not going forward with Obama’s planned rules for reducing emissions of methane, also a greenhouse pollutant, from the gas industry

Brass tacks

So far, Trump has not actually talked about these policy choices at all, or with any tangible specifics. He has merely vilified federal rules in a general way that draws raucous cheers at rallies and enthusiastic comments from fossil-fuel advocates. What comes now, in the months ahead, is a getting down to brass tacks, appointing people who will know how to do these things – things the oil, gas, coal and utility industries want. It’s likely that many or most of the people who will be appointees are currently being paid by those industries.

Even now, though, it is worth noting that implementing the entire fossil-industry agenda would not create many of the jobs Trump has promised.

Trump’s campaign often promised he would do things beyond a president’s power to do alone (for example, “cancel” an international agreement). Even though he will hold the most powerful government position in the most powerful nation in the world, he will have less power than he may think. President Obama learned this the hard way as he lost congressional cooperation. And even as Obama turned instead to use his considerable executive power, he found it limited by opponents challenging him in the courts.

What now? Disaster or deliverance? Trump’s very election is evidence that predictions about the course of the nation’s government are perilous and uncertain.

The 2018 midterm election could produce unforeseen results – either weakening or strengthening the GOP’s grip on Congress, where it will control both houses come January.

The outcome of the inevitable court cases challenging Trump’s executive actions is also uncertain, no matter who appoints or confirms new judges.

The regional politics of energy in the U.S. may likewise stall quick action, as fossil fuels continue to battle renewables, or coal battles natural gas.

Trump may have only four years in office, or as little as two years before the 2018 midterms, to deliver promised relief (jobs) to his electoral base. Otherwise, new political campaigns promising “change” may arise.

+++++

Joseph A. Davis is the Washington correspondent for Texas Climate News. An independent journalist, Davis has covered a wide range of events and issues related to the environment, energy, and natural resources in the nation’s capital for more than three decades.