By Bill Dawson

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

“Deny” means “to state that one refuses to admit the truth or existence of,” according to the New Oxford American Dictionary. When it comes to climate science and the process of manmade climate change that it documents and projects, both “deny” and “denier” are often politically charged words, hurled like grenades by climate-action advocates at their adversaries.

But political rhetoric aside, it’s impossible to, well, deny that, based on his own strong words, “deny” is simply a correct and dispassionate description for Donald Trump’s longstanding attitude toward the validity of climate science and the reality of manmade climate change. Those same words, repeated numerous times via Twitter, are reflected in various policy proposals and promises he made during his presidential campaign and republished soon after the election.

Trump has referred to pollution-caused global warming, for instance, as “bullshit” and a “hoax.” He has referred to “global warming hoaxsters.” He has alleged that “faulty science and manipulated data” are behind the nearly unanimous conclusion by scientists around the world that humans’ use of fossil fuels is dangerously warming and disrupting the climate.

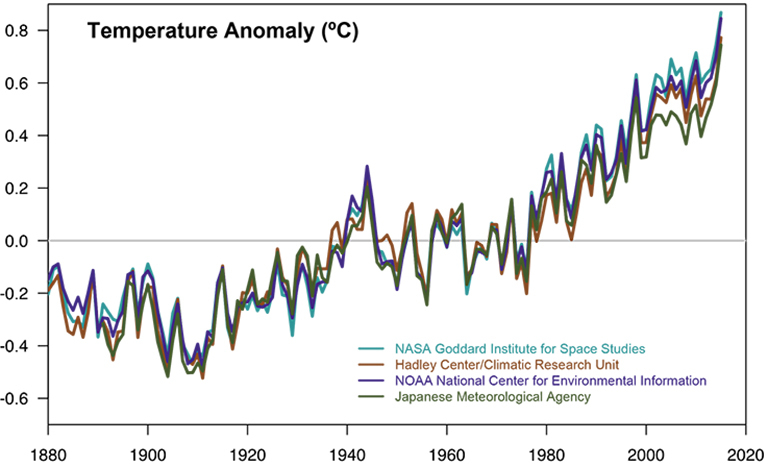

Mike Pence, Trump’s running mate, will become vice president after making compatibly similar declarations: He said global warming is a “myth” (dictionary definition: “a widely held but false belief or idea”) and claimed that the earth has gotten cooler since the mid-20th century. Independent research teams from different nations (see chart below) present evidence showing the opposite has happened. The world’s leading climate-science body says average warming since 1950 is beyond doubt (“unequivocal”) and it’s “extremely likely” to have resulted mainly from human activities.

This chart displays temperature data from four science institutions that operate independently: NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Climatic Data Center, the U.K.’s Met Office Hadley Centre/Climatic Research Unit and the Japanese Meteorological Agency. “All show rapid warming in the past few decades and that the last decade has been the warmest on record,” according to NASA, which published the chart.

Leading the Trump-Pence administration’s transition team for the Environmental Protection Agency – and reportedly a candidate to head the EPA – is Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank. Ebell’s career there is in close sync with Trump and Pence and their proposals. Over many years, Ebell (who has no professional training in science) has challenged the validity of climate science, criticized assertions that climate change poses serious threats, and opposed pollution-reducing action to limit global warming.

Only time, of course, will tell how things turn out with regard to the Trump-Pence campaign’s stated goals regarding climate and related energy issues. But Trump’s, Pence’s and Ebell’s past records – bolstered by promises on a post-election website —unavoidably suggest the new administration will mean business when it comes to achieving them. Those goals include:

- Canceling U.S. participation in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, which took effect this month. Under the accord, 195 nations – rich and poor alike – pledged voluntary and periodically strengthened emission reductions in a common global effort to prevent the most catastrophic impacts of climate change. (Geopolitical context from Mashable’s Andrew Freedman: Trump will be “the only leader of a major industrialized country to deny the existence of human-caused global warming.”)

- Abandoning the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, whose planned pollution cuts constitute the main part of the initial U.S. pledge under the Paris accord. The Clean Power Plan, now on hold pending the outcome of litigation against it by Texas and others, directs all states to develop plans to reduce greenhouse emissions that occur in the generation electricity. It’s mainly aimed at reducing reliance on coal, the dirtiest of the fossil fuels in terms of climate pollution and other, traditionally regulated pollutants that damage people’s health and the environment.

- Reviewing all of the Obama administrations coal-related regulations and ending its moratorium on new coal leases on federal lands – both of these items are in line with Trump’s declared desire to revive the declining U.S. coal industry.

- Ending all federal spending on clean energy research and development and halting federal funding for climate science research.

- Taking additional steps to boost fossil fuels, such as approving the Keystone Pipeline that the Obama administration declined to approve.The presidential election was undoubtedly the election result with the most significant – and indeed, potentially world-historical – ramifications, but it took place against a backdrop of miscellaneous climate-related votes around the country. Taken together, they offer a mixed picture.

Defeat of a Texas climate-action proponent

Lamar Smith, who has represented Central Texas’ District 21 in Congress since 1986, beat back a spirited challenge from Democrat Tom Wakely, who ran largely on the basis of his support for action against climate change and criticism of Smith’s record as a prominent and influential opponent of it. Smith got 57 percent of the vote to Wakely’s 36 percent. It was the lowest percentage Smith has recorded since first winning the seat. He received 72 percent in 2014, and climate-action proponents, despite Wakely’s 21-point defeat, hailed the result as evidence of Smith’s weakened standing among voters.

Florida voters against solar limits

Voters in Florida – urged by a coalition of environmentalists, conservative Tea Partiers and solar manufacturers – turned down a ballot measure pushed by the state’s largest investor-owned utilities that would have limited the expansion of rooftop solar installations. The coalition chairman called the proposal “one of the most egregious and underhanded attempts at voter manipulation in this state’s history,” and the Miami Herald called the wording of the industry proposal “misleading.”

Washington state voters against a carbon tax

Washington prides itself on being a very green state, both in terms of vegetation and environmental attitudes, but voters turned down a measure to enact the nation’s first carbon tax, a concept with national support ranging from devoted environmentalists to ExxonMobil. The defeated measure would have taxed fossil-fuel use, reduced the state sales tax, given rebates to low-income residents and reduced a business tax. Some environmentalists and social-justice advocates opposed it, however. Already, proponents of a carbon tax are working on an alternative proposal, with proceeds largely invested in clean energy projects.

Coloradans enlarge an obstacle facing local fracking bans

Many climate-action advocates oppose the oil-and-gas drilling method called fracking, while others say the natural gas it produces can play an important role in fighting climate change as a cleaner “bridge fuel” between coal and renewables. A circuitous fight over local bans on the drilling method led in Colorado to a court ruling that they were unconstitutional. To make it harder for fracking opponents to amend the constitution to permit local bans, the oil-and-gas industry pushed an amendment to make constitutional amendments harder to pass. Voters approved the industry amendment. (The Colorado vote echoed similar developments in Texas. The Legislature in 2015 banned local fracking bans, spurred by Denton voters’ approval of such a prohibition in that North Texas city.)

A split outcome in two Senate races

Climate-action proponents were hoping for the election of candidates friendly to their cause in two closely contested Senate races – one in Nevada to choose the successor for retiring Senate minority leader Harry Reid and one in Pennsylvania, where Republican incumbent Pat Toomey sought reelection. In the Nevada race, Democrats held onto Reid’s seat when Catherine Cortez Masto, boosted by more than $1 million in ads purchased by environmental groups, defeated Republican Joe Heck. In Pennsylvania, Toomey defeated Democrat Katie McGinty, who had never sought elective office and whose career included high-ranking environmental policy positions in state and federal government as well as corporate jobs.

+++++

Bill Dawson, founder and editor of Texas Climate News, has written about the science and politics of climate change since the 1980s for publications including the Houston Chronicle, where he was the environment writer for 17 years.