Elon Musk, new owner of Twitter, posed in 2011 at the Tesla Factory in Fremont, California. Musk, the world’s richest man, is CEO of Twitter, Tesla and SpaceX. Maurizio Pesce, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commones cropped

Katharine Hayhoe wasn’t planning to start a new list on Twitter, until last month. That’s when the Texas Tech professor and Nature Conservancy chief scientist was accused of being “little more than a priestess of a twisted religion.”

In response, Hayhoe – an eminent climate researcher and communicator who has more than 230,000 followers on Twitter – created a new Twitter list called Climate Cult Priestesses. It comprises tweets from Hayhoe and seven of her women colleagues.

The list’s tagline: “If that’s what they call us, we might as well own it!”

Drawing on everything from humor to outrage, Hayhoe and other climate scientists long active on Twitter are confronting a watershed moment. Since Twitter was taken over in October by the richest person on Earth, Elon Musk, at least two-thirds of the site’s staff has been fired or left voluntarily, and thousands of once-suspended accounts are being allowed back on the platform. (Donald Trump is among those invited back, though he hasn’t yet taken up the offer.)

On Dec. 9, three members of Twitter’s Trust and Safety Council resigned, asserting: “It is clear from research evidence that, contrary to claims from Elon Musk, the safety and wellbeing of Twitter users is on the decline.” On Dec. 12, it was reported that Twitter had dissolved the council.

The invective flung at Hayhoe exemplifies the trashing of climate scientists and climate science that appears to have ramped up since the Musk takeover, as outlined in a Guardian article on Dec. 2: “#ClimateScam: denialism claims flooding Twitter have scientists worried.”

The headline refers to the fact that at the time of the article’s publication, #ClimateScam appeared at the top of the search list when “climate” was typed into Twitter’s search engine, beating out #ClimateEmergency and #ClimateAction.

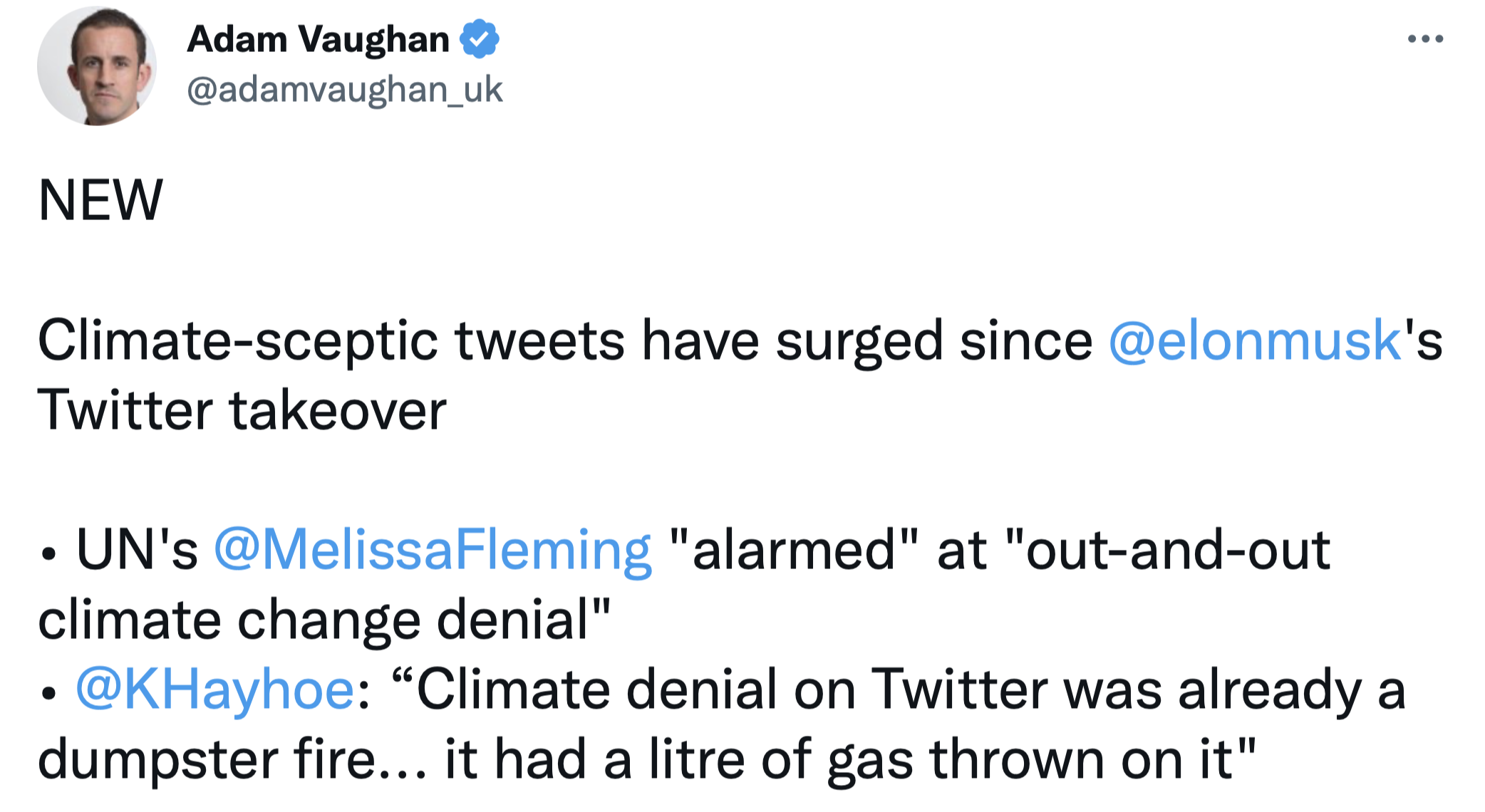

Adam Vaughan, environment editor of The (London) Times, tweeted on Nov. 29 about a new article in the newspaper.

A Dec. 8 analysis by the watchdog group Media Matters found that several prominent purveyors of climate-science dismissal and/or misinformation saw jumps in new followers since the Musk takeover. Some garnered up to 18 times their monthly average in new followers.

Others rooted in mainstream climate science noted drops in engagement for their own Twitter posts. “My 12-month average is 135 mentions per day,” reported Hayhoe on Nov. 23. “This number was maintained until a week ago, when it dropped like a rock (despite being the final days of #COP27 [this year’s United Nations climate summit]).”

From Nov. 20 to 23, Hayhoe saw less than 50 mentions a day.

“Twitter is a shadow of its former self when it comes to climate change,” Kim Cobb, a climate scientist who directs the Institute at Brown [University] for Environment and Society, told the Guardian. “As someone who followed lots of women scientists, and scientists of color, I’m noticing the absence of these treasured voices.…Maybe they’ve left Twitter, or maybe they’ve fallen silent, or maybe the network has deteriorated to the point that I’m just not seeing them being retweeted by mutuals.”

There’s no handy compass to help climate scientists as they navigate these roiling waters. Many of them have opened accounts on alternate platforms, and many are advertising those new accounts at the top of their Twitter feeds.

However, there isn’t yet a critical mass on these alternate sites anywhere close to the number of people that Twitter still reaches.

Ed Maibach is director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication. He made this announcement on Twitter on Dec. 7.

Weather and climate researcher Andrew Dessler, a professor at Texas A&M University, joined Twitter in 2013. He told Texas Climate News: “It doesn’t really matter to me if climate trolls or deniers show up on Twitter. I don’t engage with them. What matters is if the audience I do want to engage with leaves Twitter.

“Based on my admittedly anecdotal analytics, it does appear that some of my audience has left Twitter. I’ll stay here as long as there’s a reasonable audience for my thoughts.…Once that’s no longer the case, I’ll leave too.”

Geeta Persad is an assistant professor of climate science at the University of Texas at Austin who joined Twitter in 2017. The early career scientist recently used the platform to help publicize a commentary in the journal Nature on which she served as lead author, stressing the need to consider aerosols – airborne particles, including dust and soot – in climate assessments.

“Twitter has been a valuable tool for building community and visibility and for knowledge sharing in my scientific area,” Persad told TCN. “I’ve made a conscious effort over the last few years to increase my Twitter activity and build a Twitter following as part of my scientific outreach plans.

“I have seen a drop-off in the reach of my posts since the Twitter transition, and it’s disheartening to think that my investment in building a Twitter following might be wasted if the service goes under. For early career faculty, visibility and time are both incredibly important, and losing the investment in my Twitter visibility would be a blow.”

Disciplines adjacent to climate change, such as emergency management, also stand to lose in the erosion of Twitter. Before he left the company, developer advocate Jim Moffitt had been part of a team working on a new generation of APIs (application program interfaces). “These APIs are critical for real-time ‘listening’ to event-related tweets,” Moffitt told TCN.

For example, the U.S. Geological Survey’s Texas Water Dashboard uses a Twitter API-based panel to spotlight locations that are experiencing flooding or heavy rain. And a case study on Twitter’s Developer Platform shows how the #TexasFreeze of early 2021 played out on the platform.

“My main concern is whether the public APIs will continue to get support,” said Moffitt.

Where to now?

One of the most prominent of the burgeoning Twitter alternatives is Mastodon. As opposed to a single-site platform like Twitter, Mastodon is a collection of loosely federated providers, or servers, that vary enormously in size, scope and theme. Each Mastodon server has its own members and its own content-vetting practices, some more stringent than others. No matter which server you’re on, you can follow accounts from any other Mastodon server.

While the nonprofit, open-source roots of Mastodon are appealing to many Twitter refugees, some aspects of Mastodon, including its distributed nature and semi-esoteric lingo (e.g., referring to servers as “instances”) may add friction to the process as climate communicators work to preserve the reach they could lose if Twitter were to fully collapse.

Another fast-growing alternative is Post.news, still in beta stages but designed to echo the simplicity of Twitter, with an eye toward allowing some content to be “tipped” via micropayments. Post.news promises to “give the voice back to the sidelined majority; there are enough platforms for extremists, and we cannot relinquish the town square to them.”

The waiting list of 180,000 for Post.news in late November was more than ten times the number of users already active on the site. (Twitter told the Reuters news service in October that it had 238 million “monetizable daily active users” in the second quarter of 2022. Reuters also reported that a Twitter researcher had written in an internal document that the number of the most active users of the platform – “heavy tweeters” – had been in “absolute decline” since the pandemic’s start in early 2020.)

In a Twitter thread on Dec. 1, Elizabeth Sawin, director of the Multisolving Institute – a think tank that works on solutions to climate change and other knotty, overlapping issues – reported on her experience testing out several social media platforms since mid-November.

“The thing that strikes me,” Sawin said, “is how much lower the amount of information per vertical screen inch feels everywhere compared to Twitter.…Longer character limits, so posts are wordy, but not always more insightful.”

Sawin’s experience is in line with a New York Times op-ed by MSNBC news anchor and commentator Chris Hayes, “Why I Want Twitter to Live.” A self-proclaimed voracious user of the platform going back to 2008, Hayes praised how Twitter “allows me to synthesize vast amounts of information very, very quickly. Unlike message boards that are segmented by interest…Twitter is a place where all kinds of perspectives are instantly accessible and overlapping.”

At the same time, Hayes noted how Twitter has maximized the “never-ending, all-you-can-eat attentional buffet” of our wired world, and he bemoaned how “all of the worst fears [about Twitter’s future] have manifested” in the still-brief Musk era.

Hayes argued for creating a new, not-for-profit digital commons: “Because we’ve had it before, we know we can make a place to connect and learn and argue that no one person owns. We can create a collective digital life that doesn’t depend on mining every nanosecond of our attention for profit.”

Offering a stark contrast to Twitter’s recent trajectory is Project Mushroom, a Mastodon-based site being curated to put climate justice and equity front and center. Project Mushroom is an outgrowth of Currently, a national news service founded by journalist and climate scientist Eric Holthaus (long one of Twitter’s most prominent voices on climate change, with close to half a million followers).

Currently calls on a diverse lineup of local correspondents to connect weather news to climate trends and related social issues. Currently has made extensive use of Twitter along with its own website. In contrast, Project Mushroom is designed to bypass Twitter entirely.

As of mid-December, a Kickstarter campaign for Project Mushroom had drawn more than 1,700 backers in less than two months and raised almost three-quarters of its $200,000 goal in pledges.

As its Kickstarter manifesto puts it, “Project Mushroom will amplify and lift up diverse voices in justice & action. We are building a creator-first platform where users can easily find, discover and interact with each other on a safer, more inclusive platform.”

The plans for Project Mushroom include paid moderators, explicit community guidelines, an emphasis on creators from historically marginalized groups, and a range of newsletters and podcasts alongside individual creator sites.

The site is also building tools to help users find people they already follow elsewhere, and to easily invite their own followers from other platforms to meet them at Project Mushroom. Other tools along these lines include the Mastodon Twitter Crossposter, which connects Mastodon and Twitter accounts and allows for posts on one account to appear on the other (provided they adhere to length guidelines and the like).

Such tools will be crucial for any of the Twitter alternatives now sprouting, in what’s shaping up to be a period of unprecedented flux in how climate-related content gets shared among millions of people.

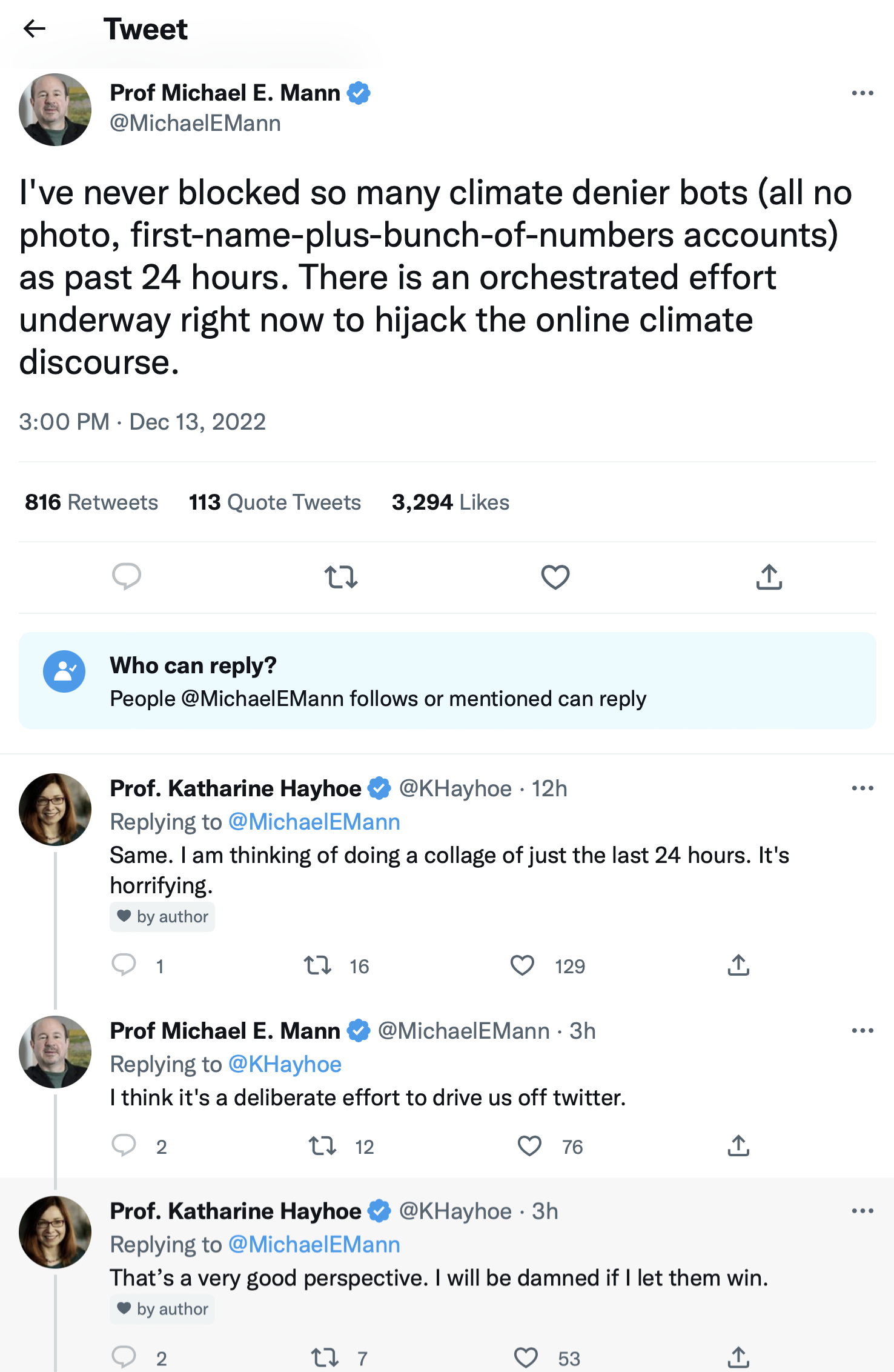

Update, December 14, 2022: Soon after this article’s publication, two of the world’s most famous climate scientists chatted on Twitter about their troubling experiences on the platform. As noted above, Katharine Hayhoe is chief scientist of the nonprofit Nature Conservancy and a professor at Texas Tech. Michael Mann is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Both are active in far-reaching efforts to communicate with the public about climate change.

Bob Henson, a meteorologist and science writer based in Colorado, is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. He is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change,” published by the American Meteorological Society.