Downtown Denton, Texas, February 2021. Andy Jacobsohn / Deep Indigo Collective for Texas Climate News

The catastrophic cold blast that enveloped Texas and neighboring states in February 2021 was unprecedented in its sheer longevity in some spots, a new study confirms. By several other measures, though, it wasn’t the worst cold Texas has ever seen.

“Even in the context of a warming climate, cold events such as this should be considered when assessing risk and hazard mitigation planning. The magnitude of impacts associated with this event suggests a lack of preparedness that needs to be addressed,” wrote the authors, led by Colorado assistant state climatologist Becky Bolinger, the Colorado assistant state climatologist, in the journal Weather and Climate Extremes. She is also a faculty member at Colorado State University.

The cold, snow, and ice of mid-February 2021 now rank as the nation’s most expensive winter weather disaster on record. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has pegged the cost at $24 billion, or more than twice the inflation-adjusted damage wreaked by the March 1993 “Storm of the Century,” which dumped snow from Florida to Maine.

NOAA attributes 262 deaths nationwide to last year’s winter storm, just behind the 270 killed in the Storm of the Century. State officials set the Texas toll at 246, the majority from hypothermia and frostbite. An analysis from BuzzFeed News examining excess deaths – the increase above typical seasonal death rates, a standard index used for events such as Hurricane Maria – estimated that the cold wave may have led to more than 750 fatalities in Texas alone.

The new paper includes a grim recap of the February 2021 storm’s varied impacts across the south central states. Beyond the now-notorious crippling of the Texas power grid, there were water supply issues extending east to Tennessee and Mississippi; citrus and vegetable losses that topped $375 million in Texas alone; and widespread cattle and poultry deaths.

A week below freezing

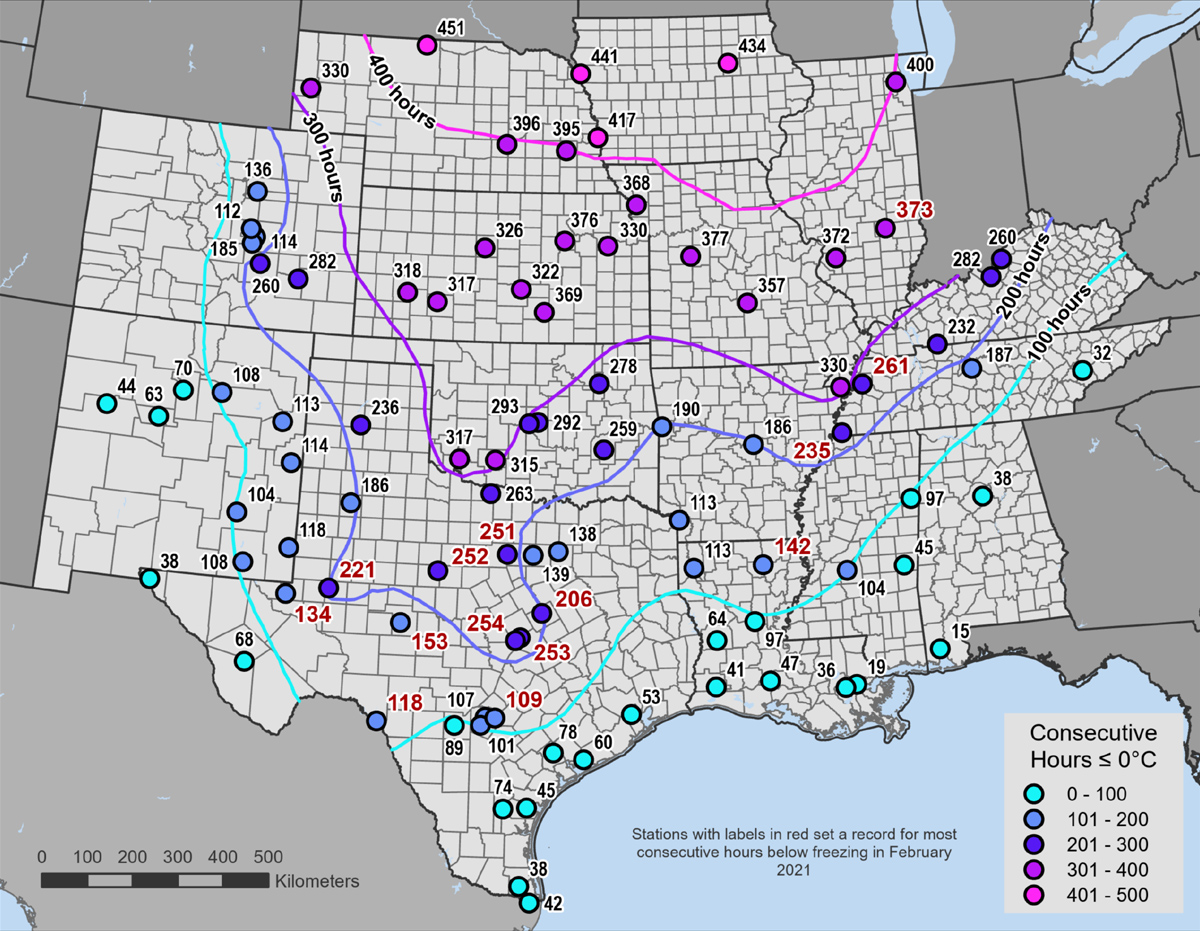

Adding quantitative heft to the lived experience of millions of Texans, the new study brings home a standout aspect of the February 2021 cold wave: its duration. Many towns and cities were stuck at or below freezing for a solid week or longer.

Among the Texas locations that set records in data going back to 1948 for their longest stretches at or below 32 degrees Fahrenheit were Waco (8 days), Midland (9 days), and Abilene and Mineral Wells (10 days each).

Virtually every place in Texas was below freezing for at least a day or two during the February 2021 cold wave, and several locations notched more than 240 consecutive hours (10 days) at or below 32 degrees F (0 Celsius). Bolinger et al., “An assessment of the extremes and impacts of the February 2021 South-Central U.S. Arctic outbreak, and how climate services can help,” Weather and Climate Extremes 36, June 2022

The effects of both heat and cold on people as well as infrastructure tend to spike when an extreme spell lasts for more than a day or two. “I think the extended duration was crucial to the power supply problems,” said Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon of Texas A&M University, also an author of the new study.

“We were already several days into the cold wave when the coldest air finally got here. Equipment that might not have frozen from a few hours of very cold weather had to deal with several days of it. Then the outages would have been much shorter if it hadn’t been cold and cloudy during the day.”

When taking into account the full spectrum of cold variables, including nighttime lows, several prior Texas cold waves are on par with the most recent event, such as those in February 1899, December 1983 and December 1989.

“The meteorological extremes of this event, while remarkable, do have precedent in the historical record,” observed Bolinger and colleagues.

Juggling two types of temperature threats

Multiple analysts have pointed to failures in energy policy that laid fertile ground for the 2021 calamity. Chief among the culprits is the need to prepare for both hot and cold extremes as climate change unfolds. The new study doesn’t wade deeply into the ongoing scientific debate on whether Arctic warming might be triggering any major change in midlatitude cold blasts, but it maintains there’s no reason to assume that extreme winter events found in the historical record can’t recur.

According to climate scientist Andrew Dessler of Texas A&M, “Texas policy makers need to do both: harden the grid for increasingly frequent hot events and continued occasional cold events.”

|

Hot weather worries

It’s not even summer yet, but May’s uncommonly warm weather and soaring power demand have brought reminders that extreme heat, increasingly boosted by climate-disrupting pollution, can threaten Texas’ grid reliability.

On Friday, May 13, grid managers urged Texans to reduce their electricity use – setting thermostats at 78, for instance — when more than six generating units went offline.

Trying to dispel worries four days later, grid-managing and utility-regulating officials announced on Tuesday, May 17, that they’re confident electricity supplies in the state will exceed record-breaking demand expected this summer.

A more sobering outlook was issued the next day, Wednesday, May 18. In a national report, the North American Electric Reliability Corp. said Texas faces “elevated” grid-reliability risk this summer because of extremely high temperatures and lingering drought.

– Bill Dawson

|

Dessler, whose scholarly work includes attention to the economics and policy aspects of climate change, points out that much colder states have robust power grids, so the Texas grid could (at least in theory) be adequately winterized to handle storms on par with 2021. “However, that will require the state government to regulate the natural gas producers and power producers, which is something they’ve not been willing to do,” he said.

Dessler added: “The way the Texas energy market is designed is also problematic. It is not designed to work well with cheap but intermittent renewable energy. So a wholesale redesign of the market is required.”

Because of its intense short-term cold, the 1989 storm was actually more extreme than 2021’s in terms of heating demand per person over 6-hour and 2-day intervals, according to research published by environmental engineer James Doss-Gollin of Rice University and colleagues last summer. What’s more, state population has nearly doubled since 1989.

“Given anticipated population growth, future storms may lead to even greater infrastructure failures if adaptive investments are not made,” the authors concluded.

In an email, Doss-Gollin added: “The impacts of the February 2021 cold snap were caused by inadequate preparedness by many agents and at many time scales. Better weatherization of the natural gas supply chain could have limited the sensitivity of gas supply to temperature; building codes that mandate more insulation for buildings could have reduced the sensitivity of electricity demand to temperature; clear communication about managing cold in the days before the cold snap (the forecasts were excellent) could have reduced the number of people who died of carbon monoxide poisoning or experienced burst pipes; and much more.”

Doss-Gollin noted that an assessment of resource adequacy developed by ERCOT, the grid-managing agency for most of Texas, for winter 2021-22 excluded the February 2021 event from its historical assumptions, “despite the overwhelming evidence that an event like this could occur again.” As he put it, “I’m not sure that we’ve learned our lesson.”

In recent months, Nielsen-Gammon has been in dialogue with the Texas Railroad Commission (which regulates oil and gas components of the power grid) about how to incorporate the risks of extreme temperatures in draft rulemaking on weather resiliency standards for natural gas facilities.

The communication is a response to a legislative directive that marked a rare departure from Texas lawmakers’ years-long disinclination to engage with climate change, or even to start planning for related weather extremes. Last year, however, lawmakers instructed state regulators to consult with Nielsen-Gammon, in his capacity as the Texas state climatologist, as they develop weatherization rules for electric generation, transmission and distribution facilities. That law, Senate Bill 3, was the Legislature’s principal action addressing the February 2021 blackouts.

A plea for climate services

One screaming message from the February 2021 disaster, according to Bolinger and colleagues, is the need to bolster information-providing “climate services.” As defined by the World Meteorological Organization, such services “equip decision makers in climate-sensitive sectors with better information to help society adapt to climate variability and change.”

Climate services can run the gamut from analyzing potential weather extremes to engaging with stakeholders and communicating with users and the public on potential risks. Of course, if users don’t respond to the services provided, it’s akin to an unnoticed tree falling in a frigid forest.

“The February 2021 event, which has highlighted both high exposure and vulnerability, is an example of how the failure to integrate climate services into planning results in a disaster,” warn the new study’s authors. “Advances in forecasting and risk communication are meaningless if there are no actions implemented to prepare for and respond to climate and weather extremes.

Bob Henson is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. A meteorologist and science writer based in Colorado, he is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change.”

John Nielsen-Gammon is a member of Texas Climate News’ Advisory Board. He serves on the Advisory Board solely in his capacity as regents professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University. Volunteer members of the Advisory Board have no authority over our editorial decisions.

Deep Indigo Collective’s self-description: “Deep Indigo Collective is a visual storytelling resource supporting news outlets reporting on the local impacts of environmental threats and the climate crisis. As a 501(c)(3) organization, Deep Indigo is proud to produce original visual journalism on behalf of our editorial partners across the United States.”