By Randy Lee Loftis

Texas Climate News

Two Republicans from Texas and Oklahoma – where oil and gas rule politics – may be about to apply their state governments’ approaches to climate change to the whole country.

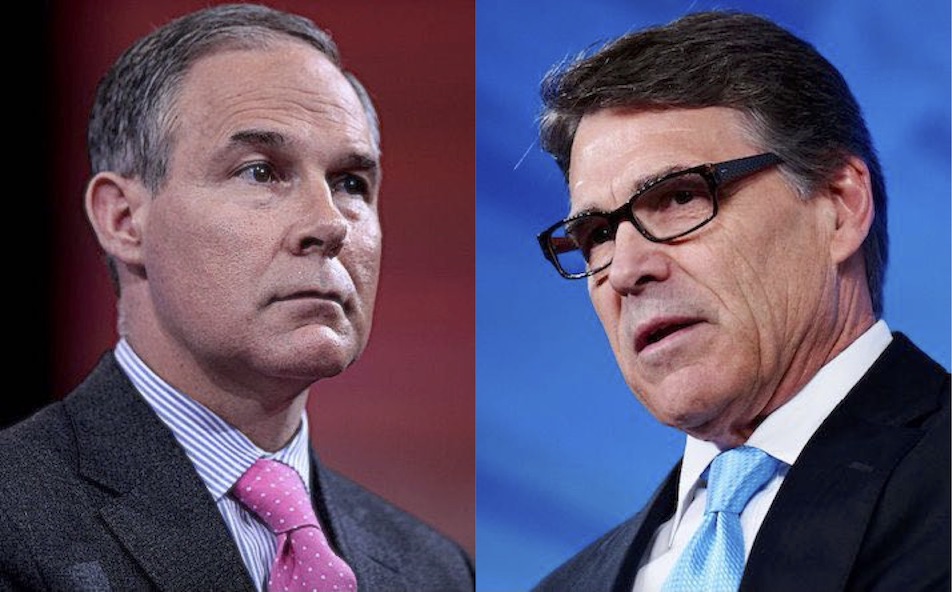

The shifts they bring might be rapid and radical if former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, nominated by Donald Trump to be energy secretary, and Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, nominated to be Environmental Protection Agency administrator, do in Washington as they did in Austin and Oklahoma City.

Trump has mocked climate science, pledged to kill the Obama administration’s climate-protection regulations, and vowed to boost the coal industry, a leading emitter of climate-disrupting pollution. Texas and Oklahoma have both insisted, in court arguments and in public statements, that the federal government is trampling the law and the Constitution by regulating emissions of climate-warming carbon dioxide. Pruitt teamed with his Texas counterparts and other states in a pending lawsuit to block proposed CO2 limits on coal-burning power plants.

More important than specific policy fights are the underlying views on climate science that they represent. Scrapping President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan would be a short-term political victory, but abandoning or censoring climate monitoring and research – in which the United States carries much of the world’s workload – could have deeper implications.

We’ve seen something like this before. Like Perry, Ronald Reagan’s first energy secretary, former South Carolina Gov. James B. Edwards, promised to eliminate rules and perhaps his own department. And like Perry, he had no energy-science background. Edwards never shook the know-nothing label. “Dentist Edwards to Quit Energy,” the Washington Post reported when he resigned after 16 months.

Reagan’s first EPA administrator, Colorado’s Anne Gorsuch Burford, was, like Pruitt, a Western Republican lawyer and ferocious opponent of the agency she would head. Her 22 chaotic months saw her slash the budget by 22 percent and abandon basic enforcement. She quit when the Reagan White House cut her adrift during a toxic-waste cleanup scandal.

Democrats controlled the House then. Today, with both chambers of Congress in Republican hands, little in the public record of Oklahoma’s and Texas’ official attitudes toward climate science gives climate advocates or scientists much comfort.

Ridiculing climate science

Leading politicians from each state (all Republicans) have ridiculed the idea of climate change resulting from human activities – which nearly all climate scientists and science organizations have called a clear and present danger, based on thousands of peer-reviewed studies over decades – as overblown or fabricated. So far, none has faced any election-day backlash for doing so.

U.S. Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma titled his 2012 book The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future. Two years later, he won his fourth six-year term. In February 2015, Inhofe brought a snowball from outside the Capitol into the Senate chamber to try to prove that global annual average temperatures aren’t rising.

Pruitt and Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin have attacked Obama’s Clean Power Plan and a federal rule to reduce oil- and gas-field leaks of methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more powerful that CO2. In 2015, Fallin prohibited state agencies from implementing the Clean Power Plan, cornerstone of Obama’s climate agenda.

On climate science itself, neither Pruitt nor Fallin has said much publicly – Pruitt will have the chance to do so during Senate confirmation hearings – but it’s probably fair to infer their opinions based on their sustained, high-volume attacks on climate action.

Fallin has ducked when questioned directly. She once said a serious Oklahoma drought might just be a natural fluctuation instead of climate change, and she suggested prayer as the response. Climate-action advocates jumped on those comments to say she’s a climate-science denier, but attributing any one drought or storm to climate change is scientifically challenging, though no longer impossible. And to call for prayer in a disaster is just Bible Belt Politics 101.

Pruitt also has been called a climate-science denier, based largely on this statement in a National Review column in May 2016 that he wrote with Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange:

Healthy debate is the lifeblood of American democracy, and global warming has inspired one of the major policy debates of our time. That debate is far from settled. Scientists continue to disagree about the degree and extent of global warming and its connection to the actions of mankind. That debate should be encouraged — in classrooms, public forums, and the halls of Congress. It should not be silenced with threats of prosecution. Dissent is not a crime.

Pruitt was referring to efforts by Democratic state attorneys general to subpoena ExxonMobil’s records on climate science to see if the oil giant defrauded investors by hiding what it knew about climate-change risks. Although Pruitt mischaracterized the vast extent of the scientific consensus, as climate-science denial goes, his statement was tame.

But Pruitt also signed a letter with 12 Republican counterparts, including Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, that threatened retaliation against clean-energy firms that, the politicians claimed, exaggerated global warming risks. Pruitt seemed even more bellicose when he tweeted out the Washington Times’ story on the letter last June 17:

Down in Texas, Rep. Lamar Smith of San Antonio, the House science committee chairman, has become that chamber’s main voice against climate action. He has suggested that federal scientists cooked the books to produce research findings that match White House politics; federal officials and scientists strongly dispute the charge. In November, Smith won his 16th two-year term.

Smith’s fellow Texan and predecessor as House science chairman, former Rep. Ralph Hall, claimed in 2011, based on no facts, that an unnamed someone – apparently the National Science Foundation, which funds federal research – bribed scientists to endorse global warming.

“And they each get $5,000 for every report like that they give out,” Hall, who served 16 terms, told National Journal. “That’s just my guess. I don’t have any proof of that. But I don’t believe ’em. I still want to listen to ’em and believe what I believe I ought to believe.”

Perry also has jumped onto the hoax-allegation train. In his 2010 book Fed Up!: Our Fight to Save America from Washington – the introduction to his failed 2012 presidential bid – he called human-induced climate change “one contrived phony mess.”

Perry, too, has accused climate scientists – most of whom work for agencies or universities and aren’t noted for their wealth – of backing global warming only because they’re corrupt. He repeated the claim, with no factual backup, in August 2011. The CBS News website headline was “Rick Perry suggests global warming is a hoax”:

The Texas governor was appearing at a New Hampshire breakfast event with business leaders Wednesday morning when he said “there are a substantial number of scientists who have manipulated data so that they will have dollars rolling into their projects.”

Perry said scientists are coming forward almost daily to question “the original idea that man-made global warming is what is causing the climate to change.” He said the climate is changing but that it has been changing “ever since the earth was formed.”

Perry added that “the issue of global warming has been politicized,” and argued that America should not spend billions of dollars addressing “a scientific theory that has not been proven, and from my perspective is more and more being put into question.”

Perry’s policy mix

As Texas’ longest-serving governor, from December 2000 until January 2015, Perry turned state policies toward the political right compared to predecessor George W. Bush. National and international momentum for climate action grew during his tenure, and U.S. figures showed repeatedly – as they still do – that Texas’ CO2 emissions were by far the nation’s biggest.

With habitats ranging from barrier islands and cypress swamps to prairies, deserts and mountains, and with its fast-growing population, Texas also has perhaps the nation’s widest range of climate vulnerabilities. Neither Perry nor the Republican-controlled Legislature ever ordered state agencies to fight climate change, prepare for it or even study it.

Under Perry, the state was always willing to claim carbon-cutting credit for things, such as the growth of wind power, that were happening anyway for reasons unrelated to climate concerns. And like Oklahoma, Texas was open to making money by hosting carbon capture and storage – technology for keeping industrial CO2 emissions out of the atmosphere by isolating them underground – if the federal government ordered emissions cuts.

Perry also urged Washington to give renewable-energy technologies “long-term regulatory and tax certainty,” an apparent signal of support for continuing federal tax subsidies for wind power. But, just as he did with support for pro-wind policies at the state level, he was boosting a Texas industry, not seeking a solution to climate change. (Besides wind, Perry also backed state policies to help Texas coal, oil and natural gas industries. He also took steps to aid the state’s fledgling solar industry – for instance, by signing laws to create the state’s solar-investing Emerging Technology Fund and Enterprise Fund – but solar power advocates say he did not support major pro-solar measures that failed to win legislative approval when he was governor.)

Meanwhile, Perry backed lawsuits against federal action to reduce climate-warming carbon dioxide emissions at industrial facilities including oil refineries and chemical plants. He also supported the initial refusal by his appointees at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality even to process paperwork for federal CO2 permits. Texas was alone among the states in refusing to do that. It didn’t stop the federal program but meant the federal EPA handled the new permits required at Texas plants. Industry leaders ultimately persuaded legislators to compel the TCEQ to start processing them.

While climate change was becoming one of the world’s major issues, Perry’s Texas government didn’t even want to mention it. Two months after his climate-hoax assertion in New Hampshire, oceanographer John Anderson of Houston’s private Rice University publicly accused Texas’ chief environmental agency of trying to censor his scientific writing on climate change. The charge prompted national and international news coverage.

The dispute exploded into public view when Anderson disclosed to the Houston Chronicle that officials of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality wanted to remove all of his references to climate change and sea-level rise, a projected result of global warming, from a chapter he had written for a TCEQ-commissioned book about Galveston Bay.

Anderson had included statistics showing that an accelerating rate of sea-level rise was placing “considerable stress on the bay and its ecosystems,” he told the Chronicle. “I don’t think there is any question but that [the TCEQ’s] motive is to tone this thing down as it relates to global [climate] change. … It’s not about the science. It’s all politics.”

Regarding the censorship issue, the Rice professor told the U.K.-based Guardian newspaper: “I like to tell people we live in a state of denial in the state of Texas.”

The independent, nonprofit Houston Advanced Research Center (HARC), which was producing the book for the TCEQ and had asked Anderson to write the chapter in question, publicly joined him in accusing the agency of censorship. Anderson and three HARC employees working on the project refused to allow their names to be included in the book if the state agency published a censored version.

Eventually, Anderson, HARC and the TCEQ reached a compromise and the book was published with his chapter. Omitted, however, were global findings about sea-level rise that had been published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading scientific body on the subject. Anderson wanted to include the IPCC data, but the TCEQ insisted on omitting them. In their place, Anderson used measurements by the U.S. government’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which ironically indicated greater sea-level rise in Galveston Bay than the IPCC numbers documented in other locations.

The resolution of the dispute suggested that Anderson’s use of statistics about sea-level rise may not have upset TCEQ officials so much as his citation of the IPCC as an authoritative science body. At that time, Texas was trying to discredit the IPCC in its legal arguments against federal regulation of climate-disrupting pollution.

Long before Perry’s book or the Galveston Bay climate censorship controversy, however, anyone paying close attention already knew that Texas was officially positioned as disputing the reality of human-induced climate change – the core conclusion of the IPCC and other leading science organizations in the U.S. and around the world.

In 2008, Perry ordered three state agency heads – two political appointees and an elected Republican – to report on the potential effects on Texas if the EPA ever decided to regulate CO2 emissions. At the time, President George W. Bush’s EPA had launched a trial balloon seeking comment on a possible CO2 rule.

Unsurprisingly, the resulting state report, which Perry immediately endorsed, predicted economic catastrophe if CO2 became a regulated pollutant. That had long been a standard Texas talking point.

Texas scientists ignored

For Texas’ view of climate change itself, the Texas Advisory Panel on Federal Environmental Regulations could have turned to the state’s biggest, most prestigious group of climate scientists – the atmospheric sciences faculty at Texas A&M University. For years, the A&M scientists have endorsed the IPCC’s findings and have stood ready to advise Texas officials on the science of climate change if they only asked.

“The faculty of the Department of Atmospheric Sciences of Texas A&M University has extensive knowledge about the Earth’s climate,” the professors said most recently in a unanimous statement on Nov. 14, 2014. “As employees of a state university, it is our responsibility to offer our expertise on scientific issues that are important to the citizens of Texas, including whether and why the climate is changing.”

They continued:

We all agree with the following three conclusions based on current evidence:

1. The Earth’s climate is warming, meaning that the temperatures of the lower atmosphere and ocean have been increasing over many decades. Average global surface air temperatures warmed by about 1.5 degrees between 1880 and 2012.

2. It is extremely likely that humans are responsible for more than half of the global warming between 1951 and 2012.

3. Under so-called “business-as-usual” emissions scenarios, additional global-average warming (relative to a 1986-2005 baseline) would likely be 2.5–7 degrees by the end of this century.

Continued rising temperatures risk serious challenges for human society and ecosystems. It is difficult to quantify such risks, except to say that the potential magnitude of impacts rises rapidly as temperatures approach the high end of the range quoted above.

Or the state officials could have consulted the American Geophysical Union, a 62,000-member, 98-year-old international scientific organization, which has many members in Texas and which stated in 2007 and again in 2013 that “human-induced climate change requires urgent action”:

Humanity is the major influence on the global climate change observed over the past 50 years. Rapid societal responses can significantly lessen negative outcomes. Human activities are changing Earth’s climate. … Human‐caused increases in greenhouse gases are responsible for most of the observed global average surface warming of roughly 0.8 degree C (1.5 degrees F) over the past 140 years. Because natural processes cannot quickly remove some of these gases (notably carbon dioxide) from the atmosphere, our past, present, and future emissions will influence the climate system for millennia. Extensive, independent observations confirm the reality of global warming. …

Actions that could diminish the threats posed by climate change to society and ecosystems include substantial emissions cuts to reduce the magnitude of climate change, as well as preparing for changes that are now unavoidable.

Another source for official Texas could have been the 13,000-member, 98-year-old American Meteorological Association, also with many Texans on its membership roster, which said most recently in 2012:

It is clear from extensive scientific evidence that the dominant cause of the rapid change in climate of the past half century is human-induced increases in the amount of atmospheric greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2), chlorofluorocarbons, methane, and nitrous oxide. The most important of these over the long term is CO2, whose concentration in the atmosphere is rising principally as a result of fossil-fuel combustion and deforestation.

Texas officials dismissed all such expertise. Out of 27 pages of text in their report, what follows is the entire treatment of climate science:

An examination of the science behind the global warming theory is beyond the scope of this report. However, recent climate research calls into question prevailing public perceptions of the cause and extent of global warming. In an “Open Letter to the Secretary-General of the United Nations,” one hundred prominent scientists presented a succinct summary of their concerns about going forward with regulation before the science is better understood: “In stark contrast to the often repeated assertion that the science of climate change is ‘settled,’ significant new peer-reviewed research has cast even more doubt on the hypothesis of dangerous human-caused global warming.” Any new regulation of CO2 emissions should be based on the best science possible.

The signatories of the letter cited by the Texas officials made their attitude toward mainstream science clear in its first sentence: “It is not possible to stop climate change, a natural phenomenon that has affected humanity through the ages.”

At the time of the state officials’ report, a massive body of research by scientists in various disciplines refuted the letter writers’ claim that doubt about man-made climate change was rapidly growing, and the letter made no ripples in the world’s science community. It did, however, find a home on websites overtly denying consensus conclusions by the vast majority of climate scientists around the world.

According to a footnote in the Texas report, the state got its copy of the letter on one of those websites, run by an organization called the Science and Public Policy Institute, whose six-person “personnel” list now includes four scientists – two climatologists, a meteorologist and a geographer.

The institute has also published materials that echo Oklahoma and Texas officials’ conspiracy-theory claims that mainstream climate scientists are perpetrating a massive hoax. One contributor to the organization’s website, for instance, asserted in 2009: “Globull [sic] Warming / Climate Change is the biggest scam of all time and is nothing more than a thinly veiled guise to prey on the fears of the ignorant to raise our taxes and erode our freedom and sovereignty!”

+++++

Randy Lee Loftis is senior editor of Texas Climate News. An independent journalist, Loftis was previously the environmental writer of The Dallas Morning News for 26 years.

Texas Climate News was published from 2008-15 by the Houston Advanced Research Center, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization. TCN’s independent journalists made all editorial decisions during that time without direction or influence by HARC or its funders.