Like many other largely conservative areas, the Texas Panhandle is a place where scientists’ almost universally held view that human activities are causing global warming and other climate disruptions can be a controversial topic.

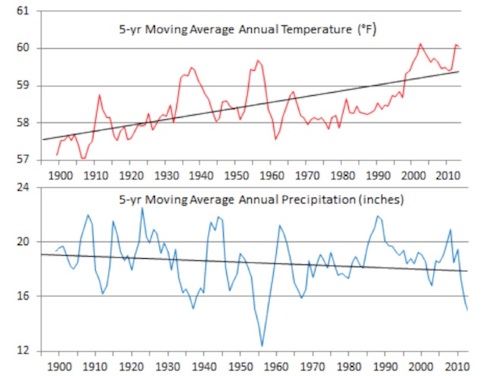

Well aware of the subject’s potential contentiousness in the Panhandle, a veteran soil scientist at West Texas A&M University steered clear of the question of causation in a report on climate trends, released Wednesday. It detailed his conclusions that a 39-county region including Amarillo, Lubbock and Midland has become “significantly” warmer, while precipitation has declined slightly, from 1895-2013.

The researcher, B.A. “Bob” Stewart, told Texas Climate News that he thinks his findings signal a continuing trend toward generally warmer and drier conditions in the Panhandle, which underscore the need for agriculture in the area to adapt.

Stewart said his findings are consistent with global patterns recorded by other scientists, but he believes it doesn’t matter for Panhandle farmers whether human beings’ activities emitting heat-trapping gases are responsible for a warming climate in their region.

“We could argue about whether you and I are causing it, but I decided to stay out of that,” he said. In the initial draft of his report, he said he included the term “global warming,” but then decided to omit it.

Stewart's analysis found that temperatures have generally risen and precipitation has generally declined in a 39-county region in the Texas Panhandle

“The message I’m trying to put across is, I’m not trying to say it’s fossil fuels,” Stewart said. “The facts are, our area is warmer, and the facts are, there’s no indication at this point that it’s going to cool down.”

Stewart has worked as an agricultural expert in the Amarillo area for nearly half a century – the past 20 years as director of the West Texas A&M’s Dryland Agriculture Institute in Canyon and for 25 years before that as director of the U.S. Agriculture Department’s Conservation and Production Laboratory in Bushland.

With that background, he knows as well as anyone that weather conditions vary in the region: Temperatures are generally lower in wet years and higher in dry years, and the state’s most notable super-dry periods since weather records began– the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s and the “drought of record” during the 1950s – were followed by cooler, wetter periods.

But even Stewart said he got “a big surprise” when his analysis of temperature and precipitation trends since the late 1800s was complete. Charting five-year moving averages of annual temperatures, “I found that it actually hotter now than it was during the Dust Bowl,” he told TCN.

Stewart's analysis of temperature and precipitation trends used data from the High Plains Division, shown in dark green – one of 10 climate divisions established in Texas by the National Weather Service.

Stewart’s analysis revealed that since about 1980, average temperatures have mostly gone up in the region, and precipitation has generally tracked downward. Because average temperatures have been higher in recent years than they were the 1930s or 1950s, declining precipitation in the High Plains – the “climate division” of the state that he studied – now is probably a result of greater warmth, he concluded.

Agriculture in the region needs to shift its focus from “changing the environment” to an approach that emphasizes adaptation to a changing environment, Stewart said:

“For 60 years, we’ve changed the environment on those irrigated acres. That’s been our focus. Now the Ogallala Aquifer is depleting pretty fast, especially in the southern part of our area, the Lubbock and Plainview area, so the higher temperature is going to make the irrigation less effective. We’re running out of opportunities to change the environment and we’re going to have to adapt to the environment.”

Agriculture will continue to have a place in the West Texas economy – likely with more production of forage for animal feed and less grain – and the region will experience relatively wetter and relatively drier years, he said.

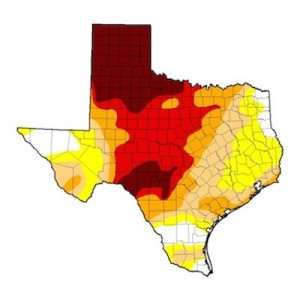

The latest assessment by the U.S. Drought Monitor, issued this week, found the Texas Panhandle is in "exceptional drought" conditions – the driest category, shown in the darkest shade of red. Virtually all of Texas was in one of the categories ranging from "abnormally dry" (yellow) to "exceptional drought."

But he added that many in the area think the current drought “will end and we’ll go back to the way we were. My concern is that these are downward trends – it’s getting hotter and drier – and I don’t think we’re going back to the same averages. I think this is becoming a drier area.”

That conclusion echoes findings for the eight-state Great Plains region, which includes Texas, in the federal government’s sweeping National Climate Assessment. The report, released last week, was produced by hundreds of government, university and private-sector scientists and technical experts.

For the Great Plains, the “key messages” included these points:

- Rising temperatures are leading to increased demand for water and energy. In parts of the region, this will constrain development, stress natural resources, and increase competition for water among communities, agriculture, energy production, and ecological needs.

- Changes to crop growth cycles due to warming winters and alterations in the timing and magnitude of rainfall events have already been observed; as these trends continue, they will require new agriculture and livestock management practices.

- Communities that are already the most vulnerable to weather and climate extremes will be stressed even further by more frequent extreme events occurring within an already highly variable climate system.

Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University, who was a lead author of one chapter and two appendices in the National Climate Assessment, issued this statement about that report in a university release:

Climate change is no longer a future issue. We are experiencing its impacts today. In the Great Plains, rising temperatures are already increasing demand for water. Future increases in temperature and shifts in precipitation patterns will constrain development, stress our natural resources, and increase competition for water among communities, agriculture, energy production, and ecological needs. For the U.S. as a whole, climate change will affect our lives through its impacts on our health, our water resources, our food, our natural environment and our economy.

+++++

[Disclosure: Katharine Hayhoe recently agreed to be a member of an advisory committee for Texas Climate News. The panel, to comprise scientists, journalists and others distinguished in their fields, is in the process of being assembled. The volunteer members will have no authority over TCN’s editorial decisions, which will continue to be made solely by our independent editors and writers. On occasion, we may report on TCN’s advisors, their work and their publicly stated views. If so, we will strive to do it impartially. We will disclose advisors’ membership on the committee when we report on them.]

– Bill Dawson

Image credits: Windmill – Leaflet / Wikimedia Commons; Stewart photo, temperature and precipitation chart – West Texas A&M University; Climate divisions map – U.S. Department of Agriculture; Drought map – U.S. Drought Monitor