By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

This week’s catastrophic flooding in and around Houston – which claimed at least eight lives, officials reported – calls for climate context.

It’s way too early, of course, for any scientific analyses of the sort that researchers call “attribution studies” – attempts to calculate how much, if any, influence manmade climate change may have had on a particular weather event.

Scientists, however, are increasingly pointing in general terms to links between warming temperatures due to carbon pollution, more water vapor in the air, and extreme downpours.

“Near-record atmospheric moisture levels”

“Suffice it to say, this was a very significant flooding storm, and delivered on the near-record atmospheric moisture levels that had been building up over Houston during the last few days,” meteorologist and science journalist Eric Berger’s Space City Weather blog reported.

The latest Houston inundation, according to an item posted Monday, qualified as that region’s “worst flooding event in nearly 15 years, since Tropical Storm Allison [in 2001] deluged the upper Texas coast and dumped in excess of 30 inches of rain over parts of the city.”

That blog post didn’t address climate change regarding the latest flood disaster to strike Houston, but a prominent Texas climate expert did.

“The new abnormal”

The Texas state climatologist, John Nielsen-Gammon of Texas A&M University, told Vice News on Monday that an upward trend in heavy downpours over Texas and other parts of the south-central U.S. is “the new abnormal.”

Asked by TCN if he had done an attribution analysis regarding recent flooding downpours in Texas, Nielsen-Gammon directed our attention to a paper he delivered last October (and published recently) at a National Weather Service workshop on the state’s all-time rainiest month, May 2015, during which inundating rainfall proved disastrous in a number of Texas locations including Houston.

In his analysis, Nielsen-Gammon observed that “the direct thermodynamic [heat-related] effect of climate change is to increase the water-vapor carrying capacity of the atmosphere. All else being equal, a saturated atmosphere that is warmer will produce more precipitation.”

He added:

A good analogy is a water faucet. The direct thermodynamic effect is comparable to the size of the pipe, which controls how much water can be delivered to the faucet. The remaining dynamic and thermodynamic effects are comparable to the handle of the faucet, which may be closed, slightly open, or fully open. The net resulting precipitation depends on both the size of the pipe and the position of the handle. However, when the handle is wide open, the precipitation intensity is controlled only by the size of the pipe.

[…]

During May 2015, near-ideal intense precipitation conditions were present in various locations across Texas. On sixteen different days, some locations in Texas received at least six inches (152 mm) of rainfall. These events occurred within every climate division of the state, and included major flooding events north of Fort Worth, along the Blanco River in Wimberly and San Marcos, and in parts of Houston. Individual events such of these appear to have been made more likely due to climate change.

With the lack of a positive trend in monthly springtime precipitation, there is no direct observational evidence that the record-setting May 2015 statewide rainfall total in Texas had an anthropogenic [human-caused] component. One study has found a possible enhancement of the springtime Texas rainfall response to El Niño. Much more apparent is the likely contribution of anthropogenic climate change to individual intense rainfall events within the month of May. This contribution is analogous to the effect of a wider pipe on water delivered by a faucet.

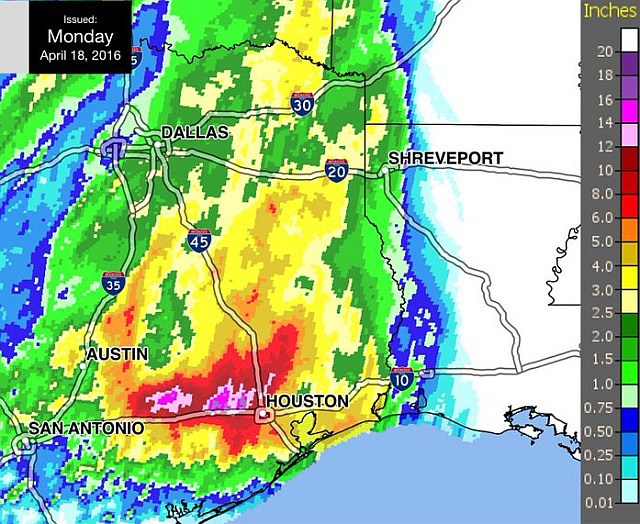

The Space City Weather blog interpreted this National Weather Service map representing total rainfall on Monday, April 18, 2016: “…[A] large swath of Texas from Lockhart nearly all the way to the center of Houston received in excess of 10 inches. Some isolated areas recorded nearly 20 inches of rain in less than a day.” [http://spacecityweather.com/after-the-worst-floods-since-allison-what-comes-next/#more-1175]

While Nielsen-Gammon drew a comparison with plumbing fixtures, Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University, looked to cardiology for her analogy to explain the link between global warming and enormous rainfall events.

Asking a climate scientist whether a disaster like the one this week in Houston is “natural” or “climate change” is akin to a heart attack victim asking a physician if the unexpected event was “genetic” or “lifestyle,” Hayhoe wrote on her Facebook page.

She continued:

Spring is the wettest season of the year in Texas – even more so during an El Niño season, which we’re still in (though heading out of, rapidly). Both spring and fall in Texas are characterized by massive frontal systems sweeping across the state, pushing heavy rain and severe weather in front of them. The state has a “genetic” or natural risk for heavy rainfall and flood during these transition seasons. This risk is even greater for Houston, located as it is on the Gulf of Mexico, which provides a nearly endless source of moisture for such storms.

As a cardiologist would say, however, often our lifestyle choices – what we eat, and how much we do (or don’t) exercise – exacerbate our health risks. In the same way, our collective lifestyle choices as the human race – depending on fossil fuels for most of our energy, as we have over the past three centuries – exacerbate our risks of heavy precipitation.

The physics connecting a warming world to heavier precipitation has been well established since the 1800s. As the planet warms, more water evaporates from oceans, lakes, rivers and streams. When the “genetic risk” of a naturally-occurring storm comes along, as it usually does at this time of year, there is now on average more “lifestyle-enhanced” water vapor available for it to pick up and dump on us than there would have been 50 or 100 years ago.

This year, though, the situation is particularly dire. Over the last few decades, we’ve seen record-breaking years and months. But these typically occur one at a time, broken up by more “normal” conditions. Global temperature records aren’t usually smashed in long continuous strings; yet that’s exactly what we’ve seen recently. 2014 was the warmest year on record, quickly surpassed by 2015; every month in 2016 has been remarkably warmer than average, so far; and NASA Goddard [Institute for Space Studies’] Gavin Schmidt, one of the smartest and most knowledgeable climate scientists I know, estimates a greater than 99 percent chance of 2016 breaking records as well.

Heaviest downpours on the rise, including in Houston

Last year, Climate Central, a nonprofit research and reporting organization, published an analysis of 65 years of rainfall records at more than 3,000 rain-gauge stations across the 48 contiguous states from 1950-2014.

The chief finding: “Across most of the country, the heaviest downpours are happening more frequently, delivering a deluge in place of what would have been routine heavy rain,” with overall increases in such events in 40 of 48 states including Texas.

Houston had a 167 percent increase in heavy downpours – defined as days when “total precipitation exceeded the top 1 percent of all rain and snow days” – which was the seventh biggest increase of all cities analyzed.

Other Texas cities on Climate Central’s list of the 50 cities with the biggest increases in were Austin (67 percent increase) and El Paso (40 percent).

Climate Central’s researchers noted:

Climate scientists predict that the recent trends toward more heavy downpours will continue throughout this century. Climate models predict that if carbon emissions continue to increase as they have in recent decades, the types of downpours that used to happen once every 20 years could occur every 4 to 15 years by 2100. As the number of days with extreme precipitation increases, the risk for intense and damaging floods is also expected to increase throughout much of the country.

+++++

Nielsen-Gammon, serving solely in his capacity as regents professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M, and Hayhoe are members of TCN’s volunteer Advisory Board. Members have no authority over editorial decisions, which are made exclusively by our journalists.

Bill Dawson is the founder and editor of Texas Climate News.