By Ruth SoRelle

By Ruth SoRelle

Texas Climate News

Climate change evokes images of people swimming out of their flooded neighborhoods, cars bumper-to-bumper as drivers flee burning homes, merciless sun that dries up rivers and lakes. However, climate change is more than these very visible disasters. Of equal or greater danger is the silent, unseen damage that may occur in the gestating fetus – damage that can last a lifetime.

In a recent article in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an international group of researchers concluded that higher temperatures caused by climate change may result in up to 7,000 additional infants with congenital heart defects in Texas and seven other representative states over an 11-year period.

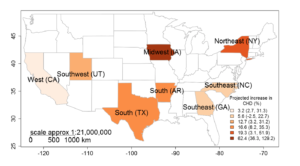

The researchers combined a multi-state database of birth defects with another of population. They integrated that with maps of temperatures across the nation and projected temperature increases from 2025-2035 to predict an increase in the numbers of infants born with serious heart defects.

In Texas and Arkansas (which the researchers defined as the South), for example, they foresee as much as a 34 percent increase in newborns with certain malformations such as tetralogy of fallot (a combination of four defects that affects the flow of blood) and as much as a 35 percent increase in another type involving a hole in the wall between the heart’s chambers.

In the Northeast they predict a 38.6 percent increase in atrial septal defect (a hole in the wall that divides the upper chambers of the heart). The Midwest is expected to have the highest increases of heat exposure to pregnant women, excessively hot days, heat-event frequency and heat event duration, when compared to the baseline period.

This study is a continuation of a 2018 study that first linked long duration of hot weather with heart defects, particularly in the southern and northeastern United States.

Scientists believe that when pregnant women are exposed to heat early in pregnancy, two problems can occur – fetal death or interference with the process in which cells generate new proteins, inducing severe fetal malformation. In the newer study, those problems appear associated with congenital heart defects.

Two Houston experts who were not involved with either study told Texas Climate News they agree that there is cause for concern.

One of them, Dr. Kjersti Aagaard, a maternal-fetal medicine expert and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, called the findings “very, very interesting, and, I think, meaningful clinically.”

The researchers “used pretty high-resolution climate projections and a robust means of measuring the rate and occurrence of congenital heart disease over a certain period. Then they project out how the burden of heart disease will potentially change as a result of the model of climate change,” she said.

Researchers projected different regional increases in congenital heart defects (CHD).

“The take-home message is that this is one of the first studies to really do a nice job of modeling climate change and human health and human disease that has a lasting effect on the disease burden in our population.

“That’s important. It brings home the point that we are not any more immune to the impact of climate disease than are other, far more vulnerable species that cannot live in a human-controlled environment. The second take-home point to me is that all of our models to estimate the cost of climate change do not take into account the increasing disease burden.

“How much is having a baby born with this severe congenital heart disease worth? A lot. I would pay a lot to prevent that from happening. I would pay a lot in my own life, and I would fight to change that trajectory as a whole.”

The researchers who conducted the study represent a consortium of international public health experts. They calculated the number of infants born with congenital heart disease from annual reports by the National Birth Defects Prevention Network and the number of live births during the baseline period (1995-2005) and the projection period (2025-2035) from the National Vital Statistic Reports and the U.S. Census Bureau.

The research team, led by Dr. Shao Lin, a professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Albany in New York, concluded that “pregnant women should be cautious of extreme heat exposure, especially during early pregnancy, and increases in the occurrences and severity of extreme heat events would increase the need for medical preparedness and care for congenital heart defects.”

For many women, such caution may be impossible, said Dr. Susan Pacheco, pediatrician and allergist/immunologist with McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

“In many instances, mothers may be unaware that they are pregnant at three to eight weeks. If you do not have access to air conditioning where you can stay cool, you are going to get exposed to those increasing temperatures, which are going to get even worse. Who is most vulnerable? It will be most dangerous in the more disadvantaged populations – minorities and the very poor. They are the ones most vulnerable, and they are the ones we are supposed to protect.”

+++++

Ruth SoRelle is a contributing editor for Texas Climate News. A veteran medical and science writer, she is an independent journalist based in Houston.