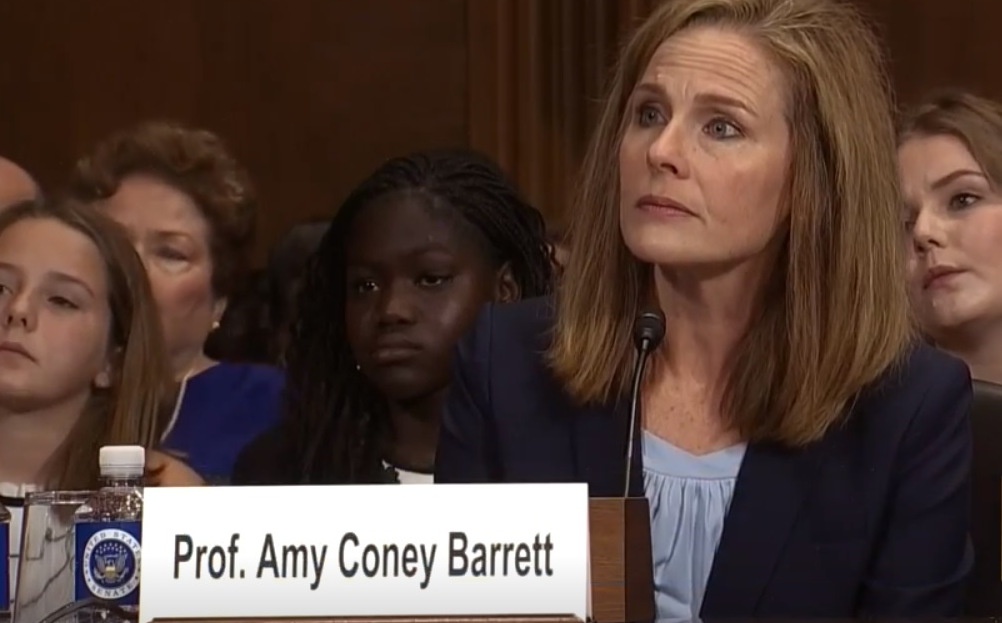

Amy Coney Barrett, testifying during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing for her nomination to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in 2017

The respected news service E&E News, which covers energy and environmental policy issues in Washington, bluntly posed an obvious question that emerged Wednesday when senators questioned Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett about climate change:

“Barrett’s Climate Answers Raise Question: Is She A Denier?”

Based on her answers, no one can say for sure if Barrett is “a denier” – one of the ever-dwindling group who deny or dismiss or downplay what scientists have sweepingly and unequivocally concluded – that pollution from humanity’s use of fossil fuels is dangerously heating the earth’s atmosphere and already is exacerbating and multiplying extreme weather events.

It was clear, however, that Barrett wanted to avoid making anything remotely resembling a definitive statement about her view of climate science and the accelerating threats of climate change. And she sought at least to give the impression that she knows little about the subject.

Yet another thing that Barrett made very clear – whether or not she was doing it consciously or had planned it beforehand – was her willingness to use talking points that opponents of action to fight climate change, some of them deniers of climate science, have long deployed.

One of those talking points, which some Republican politicians, including Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, have seemed increasingly fond of in recent years, is “I’m not a scientist.” It’s basically a shorthand way of saying, sometimes with an implied shrug and a certain tone of modesty, that they just aren’t qualified to comment one way or another on a question about climate science. (Critics often note that the same politicians who use “I’m not a scientist” to dodge climate-change questions are typically willing to speak and act on tough policy decisions involving other fields of science.)

Asked Tuesday in her confirmation hearing if she had an opinion on climate change, Barrett replied: “I’m certainly not a scientist. I mean, I’ve read things about climate change. I would not say I have firm views on it.”

Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University and the author of “The Science and Politics of Global Warming,” a textbook published by Cambridge University Press, sent this comment, responding to a request by Texas Climate News, about Barrett’s “not a scientist” remark:

Saying “I don’t know” certainly is a strategy to avoid either denying or accepting the science, either of which would make people mad. I’m sure she was expecting a question like this and made a decision that this was the best way to respond. Who knows what she actually believes.

Dessler and more than two dozen other scientists and experts at Texas universities offered to brief Abbott on the basics of climate science last year after the governor wouldn’t say whether he thinks climate change is making the state’s weather disasters, like Hurricane Harvey, more deadly. (Leading scientists, including the Texas state climatologist at A&M, have published studies concluding climate change has indeed worsened the effects of Harvey and other recent extreme weather events in Texas.)

“I’m not a scientist” was Abbott’s reply when a reporter asked him if he agrees with those findings. “Impossible for me to answer that question.”

But despite the governor’s self-professed ignorance regarding connections between climate change and Texas weather extremes, he didn’t accept the offer of an executive tutorial by Dessler and the other Texas scientists. He never responded, Dessler told TCN.

Another tactic of climate-action opponents – an old one now, which isn’t used nearly so often anymore – has been to emphasize the uncertainties in climate scientists’ findings and projections (varying levels of uncertainty are inherent in all scientific endeavor), portraying the public discourse about climate science as essentially a roaring debate, laden with controversy and contention.

As the scientific consensus about climate change – its reality, what is causing it and the serious threats it poses – has solidified and become hugely less debatable, climate-action foes have increasingly moved on to other arguments and rhetorical flourishes, stressing the costs and questioning the urgency of climate action instead of challenging the science itself, head-on.

Even so, Barrett seemed on Wednesday to be reviving the largely abandoned effort to frame climate change as basically a fierce, even toss-up, debate, fundamentally different from questions already resolved by science as to their basics.

Kamala Harris, a senator from California and the Democratic nominee for Vice President, asked Barrett in the hearing if she agrees that Covid-19 is an infectious disease, then asked if she accepts that smoking causes cancer. In both cases, Barrett quickly said yes, she accepts the scientific consensus – on Covid and on smoking.

Immediately following those questions and answers, Harris asked if Barrett thinks climate change is “happening and threatening the air we breathe and the water we drink.” It was an obvious attempt to see if Barrett accepts the scientific consensus on climate. As long ago as 2013, the world’s leading climate-science body said hundreds of researchers’ conclusion that climate change is happening and humans are “the dominant influence” was as solid as medical scientists’ conclusion that smoking causes cancer – that is, 95 percent certain.

But Barrett replied that whether climate change is “happening and threatening” is actually “a contentious matter of public debate.” She added, “I will not express a view on a matter of public policy, especially when that is politically controversial.”

TCN asked an authority on the climate issue’s scientific and political history – meteorologist and science writer Bob Henson – for his reaction to Barrett’s response to Harris’ question. Henson, author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change,” published by the American Meteorological Society, sent this comment:

One doesn’t need to get into public policy to acknowledge that human-produced greenhouse gases are warming the planet. That conclusion has been affirmed by every major scientific body on the planet. Conflating basic climate science with climate policy only serves to muddy the waters.

Amy Coney Barrett’s comment on climate change at her Senate confirmation hearing – “I will not express a view on public policy” – could just as easily apply to smoking or Covid, which also involve thorny public policy. Yet Barrett agreed that Covid is infectious and smoking causes cancer. The fact that human-produced greenhouse gases affect global climate is in the same league, and public figures ought to recognize this – especially those who could wield vast influence on climate policy through the Supreme Court.

Barrett’s own father, a longtime attorney at Shell, or his colleagues at that company could tell her that climate science is not at all “contentious” now among leaders of the oil and gas industry, whose products and processes generate mammoth amounts of the greenhouse gases disrupting the earth’s climate.

Shell is far from immune from criticism about the adequacy of its announced plans to address climate change, but its 2018 annual report is one example of its acceptance of climate science. In that document, the company expressed its strong endorsement of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, an emission-reducing pact that was based on the scientific consensus about climate change and that pledged a transition from fossil fuels to clean energy to avoid its most catastrophic consequences:

Shell has long recognized that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the use of fossil fuels are contributing to the warming of the climate system. In December 2015, 195 nations adopted the Paris Agreement. We welcomed the efforts made by governments to reach this global climate agreement, which entered into force in November 2016. We fully support the Paris Agreement’s goal to keep the rise in global average temperature this century to well below two degrees Celsius (2 degrees C) above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degree C. In pursuit of this goal, we also support the vision of a transition towards a net-zero emissions energy system.

If she takes a seat on the Supreme Court, Barrett is expected to have opportunities to rule – perhaps with momentous, history-making effect – on U.S. efforts to attack climate change and move toward a clean-energy economy, especially if Joe Biden becomes president and Democrats win control of the Senate.

Ironically, perhaps, a case that early this month the court agreed to hear involves an appeal by oil companies fighting a lawsuit by the city of Baltimore that seeks damages for climate-change impacts. The companies include Shell, ExxonMobil, BP and Chevron.

+++++

Bill Dawson, the founding editor of Texas Climate News, has covered climate science and policy issues as a journalist since 1988.