California Gov. Jerry Brown

With a recent rash of frightening wildfires, mounting agricultural losses, the entire state now mapped in the three worst dry-weather categories, and the governor warning that climate change will bring more of the same, California has understandably dominated the news media’s drought spotlight lately.

Just because California’s especially badly off, however, doesn’t mean things are so great in Texas, drought-wise.

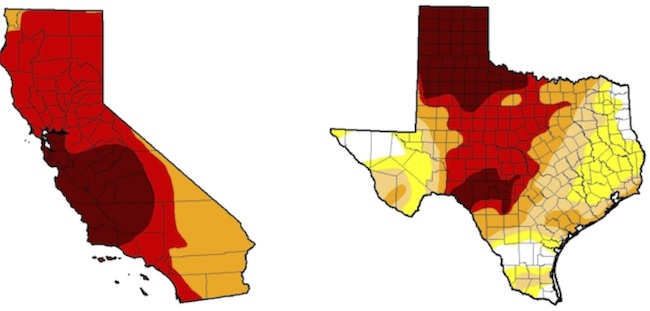

Fifty-six percent of the state is now in the three worst categories – severe, extreme and exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. That’s more than double the 21 percent at the start of the year. Twenty percent of Texas – mainly in the Panhandle – is now in exceptional drought, compared to less than 1 percent on Jan. 1.

Comparing California’s and Texas’ situations, in terms of the three worst categories, produces a (perhaps) surprising result. Although the California drought is getting more national attention right now, the total areas in the two states in severe, extreme or exceptional drought are not that different – 155,779 square miles in California and 146,551 square miles in Texas.

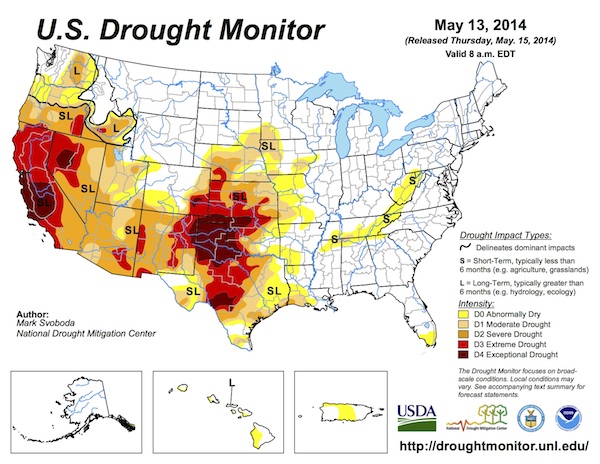

As the latest national Drought Monitor map illustrates, drought and abnormally dry conditions that don’t quality as drought are largely confined to a vast swath of the country that stretches from Texas and Plains states to its north, westward across the Southwest to California, then northward to Oregon, Idaho and Washington.

The latest Seasonal Drought Outlook issued by the National Weather Service for May 15 through Aug. 31 conveys hope for improvement in some of that area, though not in California (where drought is expected to “persist or intensify” across the whole state) and Texas (where that same expectation applies for most of the state).

In its latest Southern Plains Drought Outlook for the region including Texas, the Weather Service said the likelihood of an El Nino weather pattern was increasing, which “would have limited drought impacts through the summer but likely drought relief in the fall/winter for New Mexico and Texas.”

In both California and Texas, meanwhile, officials have been focusing on the idea of longer-term adaptation to drought conditions.

In California, that has been happening at the topmost level of state government, as Gov. Jerry Brown has used the occasion of his state’s drought to issue a series of warnings about what climate change portends.

The New York Times reported that Brown was continuing his focus on that theme this week:

Portraying California as the front line of climate change, Gov. Jerry Brown said Monday that the effects of man-made global warming were devastating the state, drawing a direct link between climate change and both the record-setting drought that has left the state parched and the early-season wildfires that broke out across California last week. He declared that people must find a way “to live with nature, not collide with it.”

Saying that California was at the “epicenter” of the impact of climate change, Mr. Brown said that states and nations in general were “not on a sustainable path” when it came to global warming and the harsh weather patterns and other problems it brings.

“We have to adapt because the climate is changing,” Mr. Brown said in a speech to scientists gathered in Sacramento for a conference on the drought’s impact on state agriculture. “Now there’s no doubt that the evidence has been strong for quite a while, and it is getting even stronger.”

There hasn’t been any adaptation talk linked to man-made climate change from Texas Gov. Rick Perry, of course. Perry, resolutely dismissive of the sweeping scientific consensus on the subject, is about as far from Brown as a fellow governor can get in his stance on the issue, having suggested in his ill-fated bid for the presidency two years ago that some climate scientists had been fudging their findings.

That doesn’t mean that government officials in Texas aren’t putting forward suggestions for adaptation strategies for a changing climate, especially for protracted drought – even if those ideas are not couched in terms like Brown’s, with explicitly cautionary links to climate change.

Wichita Falls, for example, which terms its current drought status “a Stage 5 Drought Catastrophe” on the municipal website, drew national media attention recently as the city that “may soon become the first in the country where half of the drinking water comes directly from wastewater.”

NPR reported earlier this month:

The plan to recycle the water became necessary after three years of extreme drought, which has also imposed some harsh restrictions on Wichita Falls residents, says Mayor Glenn Barham.

“No outside irrigation whatsoever with potable water,” he says. “Car washes are closed, for instance, one day a week. If you drain your pool to do maintenance, you’re not allowed to fill it.”

Barham says residents have cut water use by more than a third, but water supplies are still expected to run out in two years.

So the city has built a 13-mile pipeline that connects its wastewater plant directly to the plant where water is purified for drinking. That means the waste that residents flush down their toilets will be part of what’s cleaned up and sent back to them through the tap.

Austin, where city officials accept man-made climate change as a serious prospect and embody that acceptance in municipal policies – summarized in the desire “to make Austin the leading city in the nation in the fight against climate change” – is now considering its own wastewater re-use strategy, along with other potentially controversial ideas for dealing with water shortages.

The Austin American-Statesman reported Tuesday:

Austin is looking for more water sources as the drought persists and the lakes that Austin relies on for water continue to drop.

Some of the ideas that Austin Water Utility officials are considering, which they presented to a city committee Monday night, are likely to draw criticism from the public.

The ideas include lowering the level of Lake Austin and then pulling rainwater from it, an option previously floated by the Lower Colorado River Authority that made recreational users and homeowners along the lake unhappy.

Another controversial idea: putting reclaimed water, or treated effluent, into Lady Bird Lake. The city would allow some time for the effluent to mix in, then pump some water from Lady Bird Lake directly into a city plant located farther upstream, on Lake Austin, where water is treated and turned into drinking water.

Another potentially expensive idea would be pulling groundwater from aquifers east and northeast of Austin. Several organizations and businesses have already approached the city looking to do just that.

– Bill Dawson