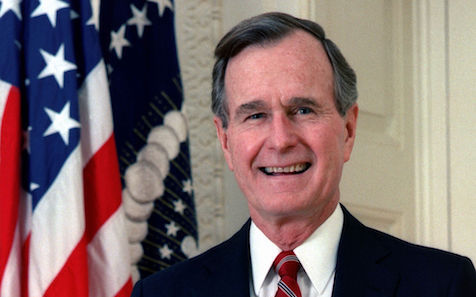

“We all know that human activities are changing the atmosphere in unexpected and in unprecedented ways.” – President George H.W. Bush in 1992

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

Everyone knows there’s a huge divide between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton on climate and related energy issues.

Well, everyone could know, if they wanted. The candidates’ stark differences on those issues (and stark is probably too weak a term here) were all but disregarded in the three presidential debates. But those differences are easy enough to learn about if anyone cares to do a little research online.

Clinton says manmade climate change is a real and growing threat. She wants to build on President Obama’s climate legacy, which includes initiatives such as the Clean Power Plan, aimed at slashing coal power plants’ greenhouse emissions. She wants to implement the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, under which nearly 200 nations pledged last December to transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources. She wants to make the U.S. “the clean energy superpower of the 21st century,” adding enough renewable energy to supply every home in 10 years.

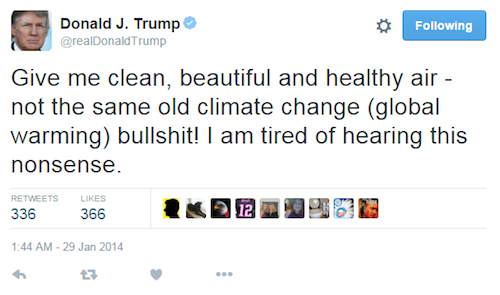

Trump has said manmade global warming, the pollution-driven phenomenon at the heart of climate change, is “an expensive hoax” and “bullshit” and was “created by and for the Chinese in order to make U.S. manufacturing non-competitive.” He wants the U.S. to withdraw from the Paris accord. He wants to “scrap” the Clean Power Plan. He says he will propose ending all federal spending on clean energy research and development and climate science. He would boost fossil fuels, approving the Keystone pipeline and boosting the U.S. coal industry.

If Trump is elected and follows through on those plans, it would, in the wording of one headline writer, be “the dismantling of Obama’s climate legacy.”

While that’s certainly true, it would also, in a way that’s far less widely recognized, mean the dismantling of the climate legacy of the second Texan to serve as president – Houston’s George H.W. Bush.

Even if Trump loses, however, his positions on climate change and related issues illustrate the Republican Party’s stunning trajectory over three decades from Bush’s positions and inclinations on those issues to Trump’s very different ones.

Bush took these actions as president, with ramifications that were fully felt only years later:

- He signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992 along with leaders of 196 other countries convened in Rio de Janeiro. The UNFCCC, as it’s known, aimed to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic [human-caused] interference with the climate system.” It is the international legal mechanism that directly led, though only after much delay and diplomatic effort and maneuvering, to the Paris agreement last year.

- He supported the then-young Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading scientific body on the subject, whose findings and projections have established the basis for pollution-reducing actions such as those pledged in the Paris accord. The IPCC, created in 1988, the last year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, with Reagan-Bush administration support, declared in its most recent major report in 2014 that warming of the atmosphere and ocean is “unequivocal” and it is “extremely likely” human influence has been the main cause since 1950. “The United States is strongly committed to the IPCC process of international cooperation on global climate change,” Bush said at a meeting of the IPCC in 1992, his last year as president. “We all know that human activities are changing the atmosphere in unexpected and in unprecedented ways.”

- He supported the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to phase out the use of chemicals depleting the protective ozone layer in the earth’s upper atmosphere, which protects humans and other life forms from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. The U.S. and other nations agreed to the Montreal treaty in 1987, when Ronald Reagan was president and Bush was vice president. The agreement went into effect in 1989, when Bush was in the White House. The 1990 Clean Air Act, championed and signed into law by Bush, implemented the Montreal pact in the U.S. Besides serving as a model for international environmental negotiations, the Montreal Protocol is the mechanism for another major climate-protection agreement last month. Reached in Kigali, Rwanda, this new agreement will phase out chemicals called HFCs that were substituted for ozone-depleted chemicals in refrigerators and air conditioners. HFCs have been found to have a warming effect on the atmosphere 1,600 greater than carbon dioxide, emitted in the use of fossil fuels and the principal human-produced greenhouse gas.

Federal records that were made public for the first time last December documented the seriousness with which both the George H.W. Bush and Reagan administrations viewed climate change. The records were posted online by the National Security Archive, a research program based at George Washington University in Washington, after they were obtained through a request under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act.

Some excerpts from the National Security Archive’s appraisal:

In connection with the Montreal Protocol (negotiated in 1987 and put into effect in 1989), both Reagan and Bush 41 showed a clear desire to tackle environmental concerns and to lead the global community in that effort, according to the documents. Protests by the Domestic Policy Council, led by Attorney General Edwin Meese, and other agency heads led Reagan to step in to ensure adoption of the final set of U.S. objectives for the treaty. Bush basically shared his predecessor’s views on entering office in January 1989.

Both presidents’ secretaries of state, George P. Shultz and James A. Baker III [of Houston], played key roles in blocking efforts by other Cabinet secretaries to frustrate implementation of more environmentally friendly policies. For example, memos for senior State Department officials in [the December] posting note that “global climate change is the most far reaching environmental issue of our time” and that notwithstanding the need for continued research, “We simply cannot wait – the costs of inaction will be too high.”

[…]

Recently declassified documents provide evidence that there was a keen appreciation by the Reagan and Bush I administrations of the need to address global environmental challenges, in particular those related to human-driven degradation of the atmosphere and global warming. Despite its overall ideological adherence to small government and free market economics, the Reagan administration did demonstrate significant U.S. leadership in tackling the risks posed by the production and use of ozone-depleting chemicals. Similarly, the George H. W. Bush administration entered office in 1989 with an eye towards building on this leadership to push for international conferences to address a wide range of environmental problems, including climate change. The Bush I administration would back off from this stance, however, in the face of growing business opposition to strong steps to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases, leaving it to the Clinton White House to revitalize U.S. leadership on these issues.

An announcement in August underscored what those released documents had revealed. Two key environmental officials of the Reagan-George H.W. Bush era – former Environmental Protection Agency chiefs William Ruckelshaus (Reagan) and William Reilly (Bush) – endorsed Hillary Clinton. They declared in a joint statement that Trump has displayed “a profound ignorance of science and of the public health issues embodied in our environmental laws.”

The two former EPA administrators leveled special criticism at Trump’s stance on climate change, calling it “the singular health and environmental threat to the world today.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founder and editor of Texas Climate News.