Weather is not climate, scientists remind us. lt’s wrong, then, to attribute the current record-setting Texas drought, which began in 2008 and has continued to grip much of the state this year, to human-caused climate change.

Weather is not climate, scientists remind us. lt’s wrong, then, to attribute the current record-setting Texas drought, which began in 2008 and has continued to grip much of the state this year, to human-caused climate change.

Still, climate scientists and others who convey their projections also have been warning, as the drought progressed, that global warming will likely bring such conditions to Texas more frequently in decades ahead.

On Aug. 22, for instance, Retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Richard Engel, director of the Climate Change and State Stability program of the National Intelligence Council, told the Southern Governors Association (whose most westerly state is Texas) that climate change will bring conditions including “intense droughts in the Southwest.”

Increasingly frequent droughts were projected for national regions including Texas in a major new federal report in June.

And earlier this year, writing in a new edition of The Impact of Global Warming on Texas, state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon of Texas A&M University had this to say:

Drought is expected to increase in general worldwide, because of the increase of temperatures and the trend toward concentration of rainfall into events of shorter duration. In Texas, temperatures are likely to rise, and future precipitation trends are difficult to call, so it is likely that drought frequency and severity will increase in Texas. If temperatures rise and precipitation decreases, as projected by climate models, Texas would begin seeing droughts in the middle of the 21st century that are as bad or worse as those in the beginning or middle of the 20th century.

Nielsen-Gammon issued a status report [pdf] on the 2009 drought conditions on Aug. 12. Among its conclusions:

- The current drought is probably the worst on record for nine counties in Central and South Texas – Bastrop, Bee, Caldwell, Duval, Jim Wells, Lee, Live Oak, San Patricio and Victoria.

- In a number of neighboring counties, the 2009 drought is more intense than most of the major droughts of the past 110 years.

- The 2009 drought is like droughts of 1925 and 1953, which also had “simultaneous extreme drought and heat,” and unlike most other South Texas droughts, which did not have the extreme heat.

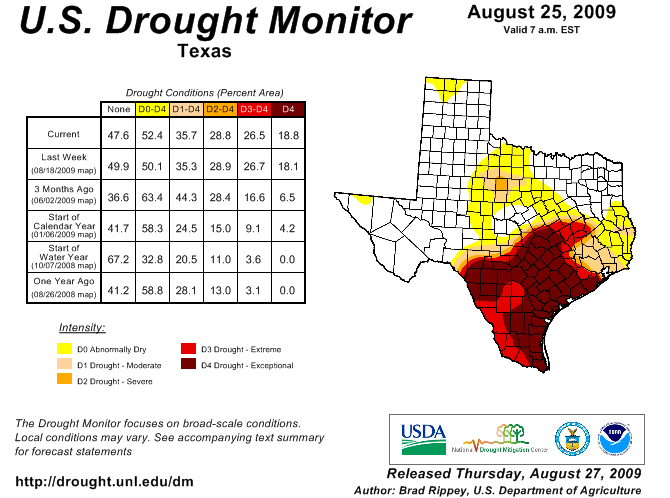

Last week, in its most recently issued update assessment, the U.S. Drought Monitor said about 52.4 percent of Texas was experiencing some degree of drought conditions, with 26.5 percent of the state in an “extreme” or “exceptional” drought – the two most severe categories. Some details from the report:

- “Historic drought continued to grip southern Texas where San Antonio closed in on its driest two-year period on record.”

- “San Antonio’s tally of 100-degree days continued to climb,” with 56 such days recorded through Aug. 25, eclipsing the city’s former annual record of 36 days in 1998.

- “By August 23, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that 46 percent of the rangeland and pastures in Texas were rated in very poor to poor condition.”

- Adverse effects on crops included corn (39 percent in very poor to poor condition), sorghum (39 percent), cotton (29 percent), and rice (21 percent).

- “Late-August water levels in the Colorado River basin near Austin were about 20 feet below the historic August average on Lake Buchanan and nearly 34 feet below average on Lake Travis.”

News accounts have provided a mosaic-like picture of the unfolding situation in recent weeks.

On Aug. 1, the Austin American-Statesman tersely reported a Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) meteorologist’s judgement that July was “the hottest month ever recorded” in the state capital. A week later, the same newspaper reported a “patchwork response to the drought” by cities in Central Texas:

The state requires all water suppliers to have a plan for lowering water use in case of drought. But determining just how severe the drought is, how much water use should be restricted and, finally, how to enforce watering restrictions is left up to the cities and utility districts.

In Austin, Lago Vista, Marble Falls, Manor, Wimberley and Lockhart, as well as Travis Water Control and Improvement District No. 17, which stretches along part of western Travis County, homeowners cannot water more than twice a week. In Buda, Kyle and San Marcos, watering is limited to once a week.

Other Central Texas cities are more permissive about water use. Burnet, Cedar Park, Georgetown, Round Rock and Bastrop encourage residents to conserve, but they have no mandatory outdoor watering restrictions.

On Aug. 14, six days later, the American-Statesman reported that LCRA was urging area residents to cut water use by 25 percent.

Last week, based on a request from the Brazos River Authority because of water levels in Lake Georgetown, additional Central Texas cities including Georgetownand Round Rock announced mandatory water-use restrictions, including limits on outdoor watering and a ban on charity car washes.

USA Today took note of the hot, dry conditions in Texas on Aug. 17 with an article and slide show on this year’s especially severe summer “wildfire season.” An excerpt:

There have been nearly 62,000 wildfires across the USA this year. No state has been hotter than Texas. A withering, two-year drought in central and southern Texas has sparked a wildfire season that has already destroyed the most structures in state history.

The fires have scorched more than 660,000 acres in Texas. Only Alaska has seen more acres burn this year — 2.8 million — but those are mostly in vast wildlife preserves, where officials allow the fires to burn, said Randy Eardley of the fire center.

The drought’s unfolding impact on Texas agriculture has been tracked, meanwhile, in reports by news outlets including Texas A&M’s AgriLife News and News 8 Austin, a cable news channel.

AgriLife News reported on July 20 that agricultural losses totaled $3.6 billion by that point and by year’s end could exceed the $4.1 billion loss sustained in 2006, according to agricultural economists at A&M.

Later reports from the news service provided details. For example, an Aug. 12 articlereported that Kleberg County, home of the legendary King Ranch in South Texas, had lost its entire cotton crop to drought for the first time in more than a century, while cotton in neighboring counties had not done much better.

On Aug. 25, an AgriLife News article reported that cattle had started dying on ranches west of Corpus Christi as a result of drought conditions – 3 to 5 percent of the herds of ranchers with whom a quoted extension agent had spoken.

News 8 Austin, meanwhile, has produced a string of stories on agricultural impacts, reporting a “bleak” outlook for corn crops in June, a hay shortage on Aug. 2, harm to grape growers on Aug. 9 and expectations of smaller pecans on Aug. 21.

Last Friday, News 8 reported that the Texas Farm Bureau’s Gene Hall was concerned that the total impact could approach $4.6 billion this year, depending on weather conditions through the remaining four months.

There could be a break in the drought, according to state climatologist Nielsen-Gammon.

In his Aug. 12 report, he noted that the National Weather Service has forecast El Niño conditions persisting through winter in the Pacific. Since that usually means above-normal rainfall across Central and South Texas, it would make it likely that the state’s drought will become “much less severe” in fall and winter, he wrote.

– Bill Dawson

[Disclosure: The new edition of The Impact of Global Warming on Texas, quoted in this article, was commissioned by the Houston Advanced Research Center, which publishes Texas Climate News.]