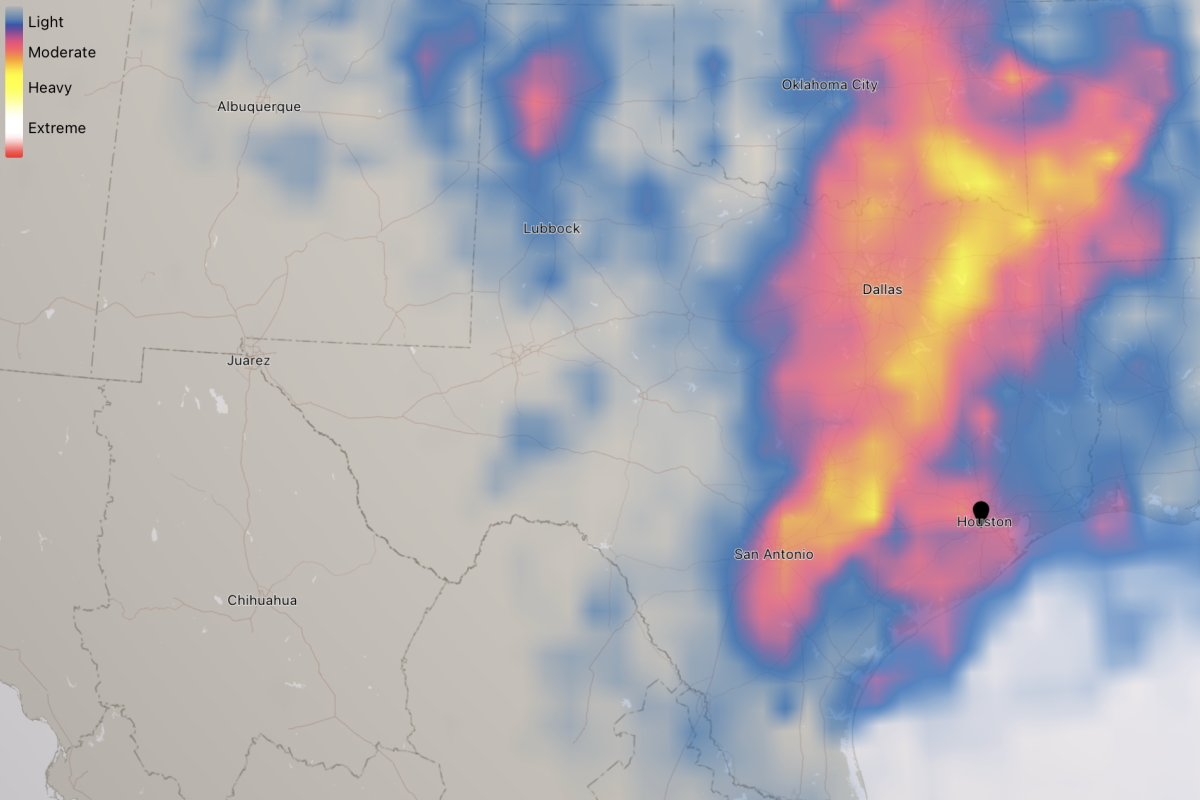

Stormy weather over Texas, May 18, 2021. iPad screen capture, Dark Sky app

With this article we introduce Texas Climate News Digest – a new feature that we’ll be publishing occasionally. Each Digest article will present a summary selection of recent news with a common theme or a close connection, enhanced with explanatory context and links for further reading.

We’ll tap a fluctuating variety of sources including news reports from reliable outlets, scientific studies, announcements by government agencies and others, and our own reporting.

So much is happening in the realm of climate change, energy and interrelated subjects, we know it’s hard to keep up with even the most prominent reports. Texas Climate News Digest is designed to help. Many installments will deal mainly with Texas, others will mainly focus beyond.

This inaugural Texas Climate News Digest presents an overview of recent developments involving heat, drought and megadrought, rainfall, new “climate normals,” heat waves and power outages.

In considering the climate disruption unfolding as fossil-fuel pollution heats up the planet, it’s good to recall that scientists emphasize the difference between weather and climate.

In considering the climate disruption unfolding as fossil-fuel pollution heats up the planet, it’s good to recall that scientists emphasize the difference between weather and climate.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration puts it this way: “Weather reflects short-term conditions of the atmosphere while climate is the average daily weather for an extended period of time at a certain location.” The agency then adds, with a touch of wit: “Climate is what you expect, weather is what you get.”

There have been ample recent reminders of the interplay and relationship of weather, (including sometimes dangerous extreme events) and climate (both near-term and longer-term). The storms that buffeted eastern parts of Texas last week with torrential rains, intense winds and flash flooding prompted NOAA to alter its three-month climate outlook for the state.

On April 15, NOAA predicted that through July the drought and abnormally dry conditions then affecting two-thirds of Texas would persist or expand, with below-normal rainfall across most of the state, through July. Last week’s heavy rains prompted the agency last Thursday to update the outlook. Its forecast now predicts drought mainly in parts of West Texas through August, with normal precipitation levels over most of the state.

One thing that did stay essentially the same in the update: As they did in the April outlook, the NOAA forecasters still say chances are good for above-normal temperatures across Texas, now extending that prediction through August.

New “climate normals” recorded in Texas

Hotter weather and its challenges comprise one key element of longer-term climate-change forecasts for Texas in coming years and decades. The last National Climate Assessment, released in 2018, said the annual number of days when temperatures will exceed 100 degrees F in the state is projected to increase “markedly” in scenarios with both lower and higher emissions of greenhouse pollutants.

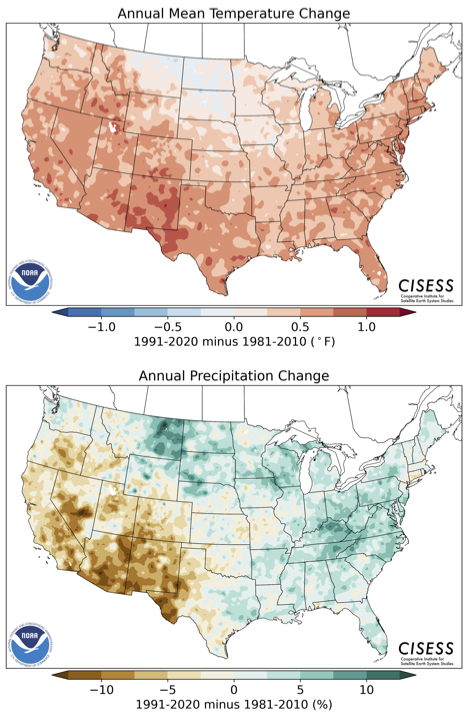

Early this month, NOAA released its latest “climate normals” report – an assessment that takes a considerably longer-range view than the three-month climate updates that are updated monthly. The new “normals” report showed that temperatures across all parts of Texas have continued to increase in recent decades, as they have across most of contiguous 48 states.

The “normals” reports, based on measurements from more than 9,000 reporting stations, are updated every 10 years. In this new version, readings from 1991-2020 were compared to those from 1981-2010.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

In Texas, the assessment revealed that mean temperatures changed by at least 0.75 F in almost all of the state, with increases of at least 1.0 F in some parts of the state, particularly West Texas. Precipitation decreases were recorded in about half of the state in the same study, especially in West Texas, with increased rainfall in about the other half.

The increased rainfall won’t necessarily always translate into decreased chances of drought as temperatures heat up, however, because scientists say climate change is increasingly bringing rains in intense bursts.

The 2018 National Climate Assessment explained the connection in a summary of what scientists generally expect in Texas:

“[T]he frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation are anticipated to continue to increase, particularly under higher [emission] scenarios and later in the century. The expected increase of precipitation intensity implies fewer soaking rains and more time to dry out between events, with an attendant increase in soil moisture stress. Studies that have attempted to simulate the consequences of future precipitation patterns consistently project less future soil moisture, with future conditions possibly drier than anything experienced by the region during at least the past 1,000 years.”

The dangers of overlapping blackouts and heat waves

February’s abnormally intense cold and the catastrophic collapse of Texas’ power grid underscored a couple of climate-change realities:

A planetary climate that’s generally heating up over spans of years and decades doesn’t mean there will be no more super-cold weather – in fact, climate changes resulting from global warming may contribute to some cold-weather extremes.

Also, with the electricity grid and other critical infrastructure vulnerable to extreme weather conditions, those extreme conditions can produce deadly results, and not just in situations that may more readily come to mind, like hurricanes. Besides billions of dollars in property damage, the February power outages reportedly caused nearly 200 deaths.

In Texas, where very hot weather extremes are more common than extremely cold conditions, a couple of new appraisals of the hazards of extreme heat have special relevance.

In a study published this month, researchers calculated that a heat wave coinciding with power blackouts would produce elevated risks of heat exhaustion and/or heat stroke, indoors and outside, for 2.8 million residents of the three cities they studied – Atlanta, Detroit and Phoenix.

“A widespread blackout during an intense heat wave may be the deadliest climate-related event we can imagine,” Brian Stone Jr., a professor at Georgia Tech and the study’s lead author, told the New York Times, adding that such situations are “increasingly likely.”

The researchers also found that cooling centers in the three cities could handle no more than 2% of their populations, while circumstances when they can be needed are increasing.

“The potential for critical infrastructure failures during extreme weather events is rising,” they wrote. “Major electrical grid failure or ‘blackout’ events in the United States, those with a duration of at least 1 hour and impacting 50,000 or more utility customers, increased by more than 60% over the most recent 5-year reporting period.”

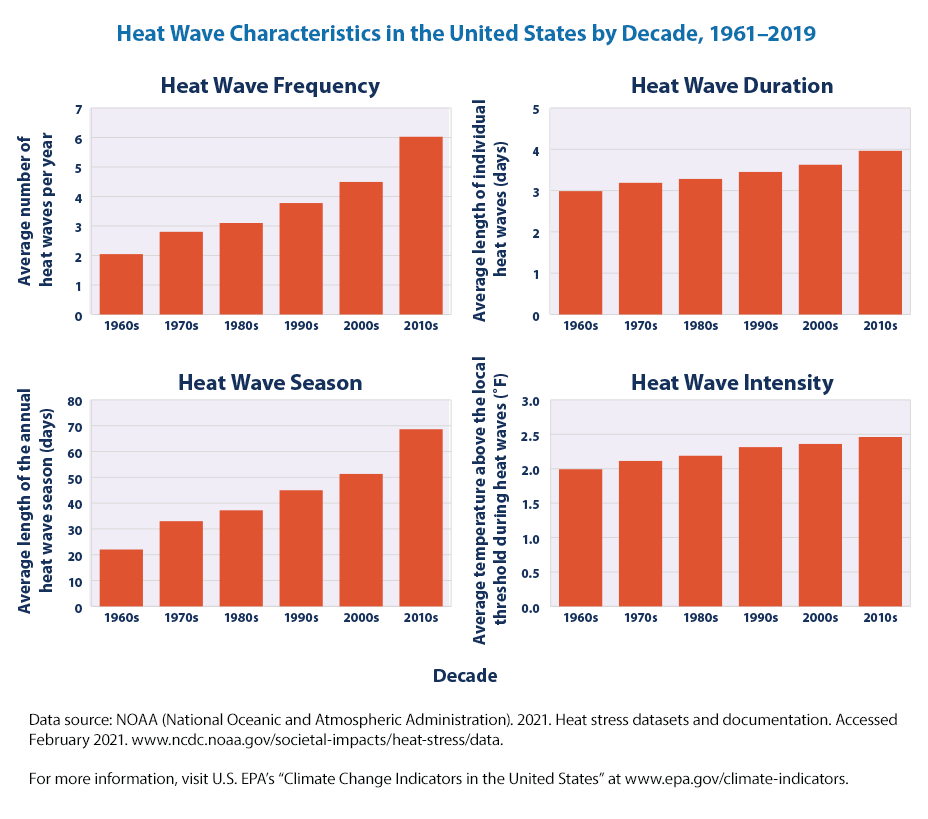

Environmental Protection Agency

The Environmental Protection Agency published updated statistics this month about climate-change risks, including heat waves – something it had been forbidden to do for the past four years by the Trump administration, which followed the former president’s lead in dismissing the seriousness of climate disruption.

The updated statistics showed that a from 1961-2019, heat waves in the U.S. have steadily increased each decade in terms of their frequency, intensity and duration, as well as in the average length of the “heat wave season” when the occur.

On May 6, ERCOT, the electric grid-managing agency for most of Texas that came under withering criticism over the February blackouts, forecast record power demand this summer. ERCOT said it expects there to be enough generation to meet that demand, but left open the possibility of shifting into “emergency operations” on the hottest days – using extra power sources – to keep up with consumption.

“The state grid manager in November had forecast it would have enough power generation to meet demand during the past winter — a forecast that would prove to be remarkably mistaken,” the Houston Chronicle noted.

Megadrought, West Texas and climate change

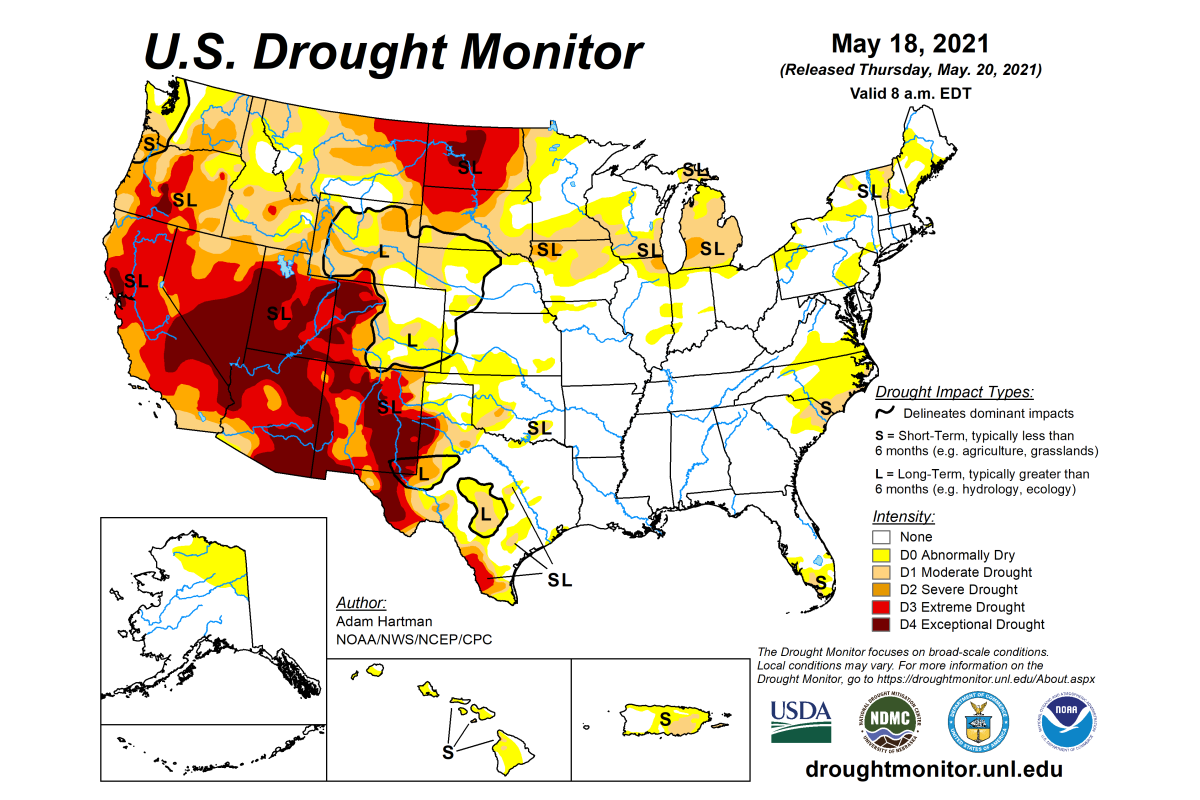

The multi-agency U.S. Drought Monitor’s most recent weekly appraisal of the 48 contiguous states, issued last Thursday, indicated slightly more than half of Texas (52 percent) was experiencing drought or abnormally dry conditions. That was down from 66 percent a week before and an even bigger improvement from the 91 percent recorded on Jan. 1. Rains last week and this week herald a continuing decline when this week’s update is issued.

Notably, however, drought (including the Monitor’s most severe category, “exceptional drought”) persists in the state’s trans-Pecos and Panhandle regions. That area marks the eastern extent of a huge swath of the southwestern U.S. that is in “exceptional drought” amid a much larger area experiencing less extreme drought conditions, prompting widespread concerns about problems that include water supplies and wildfires.

U.S. Drought Monitor

They aren’t concerns born of relatively short-lived weather fluctuations, as National Geographic reported earlier this month:

“The situation is unlikely to improve in the near future, scientists say, as 2021 shapes up to extend the ‘megadrought’ that researchers have found to be gripping the region mostly unabated since 2000.”

“Megadroughts,” in scientists’ terminology, are unusually severe dry spells, lasting at least 20 years. A study published last year in the journal Science assessed the 19-year period from 2000-18 in southwestern North America. Using hydrological modeling and 1,200 years of tree-ring-based reconstructions of soil moisture, the researchers concluded it was the region’s second-driest megadrought since the year 800 CE. Only a megadrought in the late 16th century was drier.

Natural climate variability accounted for about half of the current drought’s severity, they calculated, with nearly half (46%) caused by global warming caused by fossil-fuel pollution, they wrote. Manmade global warming has “push(ed) an otherwise moderate drought onto a trajectory comparable to the worst southwestern North America megadroughts since 800 CE.”

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.