A look at the carbon-neutrality plans of three universities and a community district shows signs of progress toward net-zero emissions, but also a long road before they reach that climate-action goal.

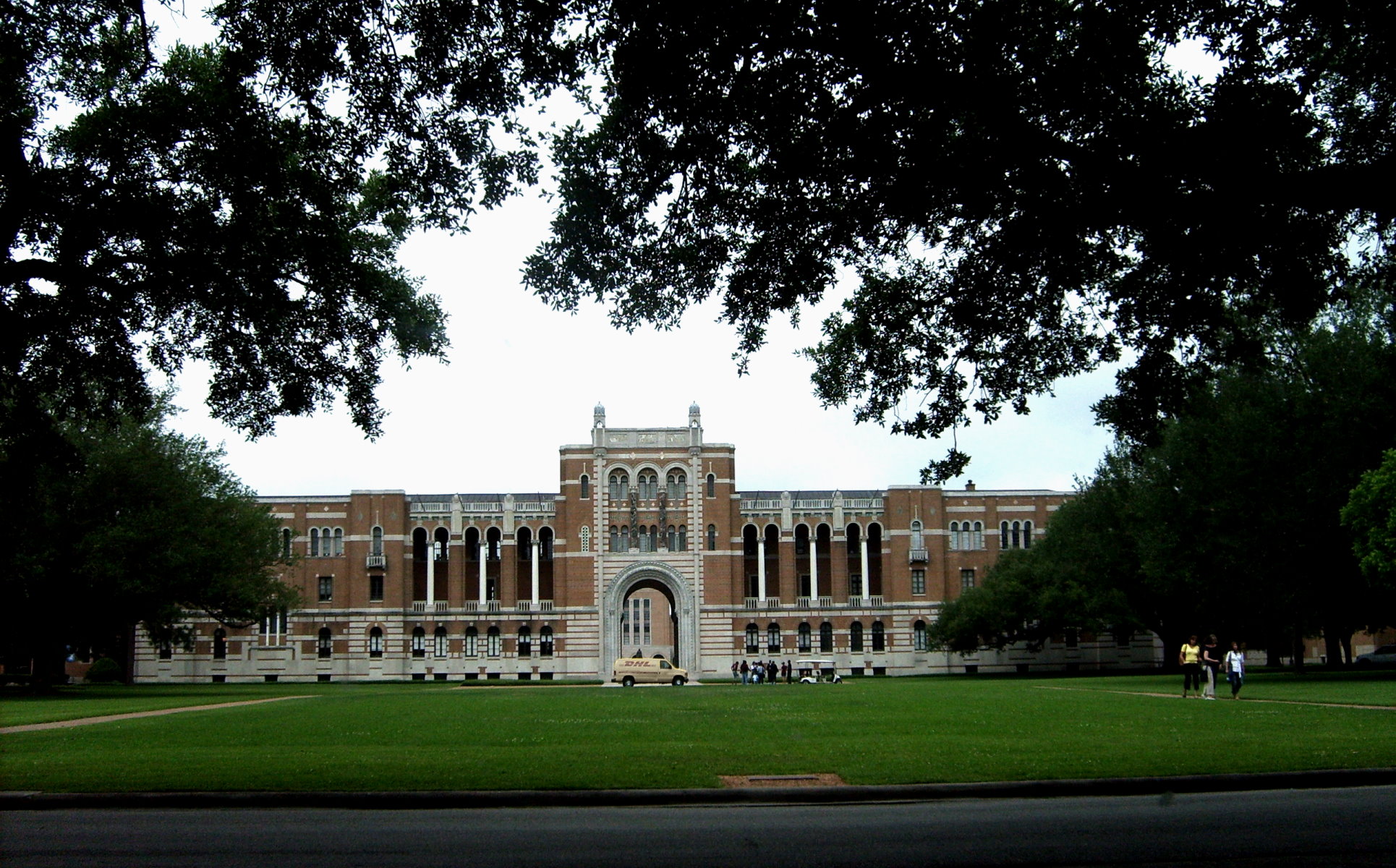

Lovett Hall, Rice University

Interviews for this story were conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted normal operations at universities and colleges across the country. As higher education grapples with online learning, canceled graduations and planning for an uncertain future, it’s unclear what will happen with on-campus sustainability goals and actions.

At colleges and universities across Texas, sustainability officers have been debating how their schools could go carbon neutral – achieving net zero emissions of climate-warming carbon pollution by ceasing emissions or removing them from the atmosphere.

Texas students have started to demand their school take action on climate change, or at least ramp up on-campus sustainability efforts. Some schools have concrete plans in place to address greenhouse-gas emissions. Others are just starting to evaluate sustainability on their own terms and tackle the low-hanging fruit.

For more than a decade, hundreds of universities across the country have grappled with the challenge of achieving carbon neutrality, providing a look at the struggle to go carbon neutral in miniature. Many schools are essentially small cities within a city, or towns within a town, working to cut out energy waste, boost renewable energy usage and electrify transportation. Yet the goal of carbon neutrality remains elusive. By 2020, only a handful of schools in the United States have actually achieved these lofty aspirations, many with assistance from purchased carbon offsets – actions to reduce emissions elsewhere for emissions at the school itself.

Carbon neutrality is a challenge regardless of a school’s geography or politics. It is tempting to think sustainability is less important for schools in red states, but that is not the case, says Julian Dautremont, director of programs at The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE), which provides self-reporting frameworks, events, and other resources for university and college sustainability offices. Schools in red states, for example Arizona State University, have even become sustainability leaders. Dautremont also praised the sustainability programs at Texas schools, including the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University.

In 2020, renewable energy is a much more attractive option for many colleges than it was even just a few years ago, giving many institutions hope that carbon neutrality is in reach. And sustainability is – or is becoming – a priority at many schools. But remaking a school’s energy mix is a major undertaking, and leading climate scientists have said the clock is ticking on a ten-year window to take decisive and meaningful action to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. (One of the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement for avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.) If universities and colleges in Texas are going to be part of the solution, they still have a lot of work to do.

For this story, Texas Climate News talked to four institutions – a large flagship state university, a network of community colleges and two private universities – as examples of what’s happening with carbon-neutrality goals and plans in different settings. (Utilities and Energy Services at Texas A&M did not respond to repeated attempts to interview them for this article.)

Rice University

Of the schools considered in this story, Rice University in Houston is one of just two with a formal carbon neutrality plan in place. In 2013, Rice set a goal to be carbon neutral by 2038. But in 2020, that plan is already out of date, says Richard Johnson, director of the Administrative Center for Sustainability and Energy Management at Rice. “One of the things that I have concluded since then is that the shelf life of plans like that is probably between five and eight years,” he says. “We’re at a point where we need to give it a significant update.”

The plan’s obsolescence is largely a good sign, Johnson says, as renewable energy has made major strides in the last seven years in terms of efficiency, affordability, and scale, and new options have opened up that didn’t exist when Rice made its original plan. These new options will have to be taken into account when Rice starts updating its carbon neutral plans this year.

In the updated plan, one of the questions the school will have to answer is whether to move that 2038 deadline up a few years. “I think both the urgency and the ability to address it are heightened,” Johnson says. As a residential university, Rice’s biggest source of emissions is campus buildings, he says and reducing emissions from heating, cooling, and lighting will pose the greatest challenge for achieving carbon neutrality.

Rice has started to make strides on this front, Johnson says, focusing on renovating existing buildings to make them more energy efficient and shifting the focus away from putting up new buildings, when possible.

Dallas County Community College District (soon to be Dallas College)

Of the seven colleges that make up the Dallas County Community College District (DCCCD), most have climate action plans and carbon-neutral goals, says Georgeann Moss, executive administrator for sustainability outreach and initiatives. But in June, those colleges will come together under the banner of one school – Dallas College – operating at multiple locations. As part of the administrative consolidation process, the seven different approaches to climate change will have to be converted into one overarching approach for the whole school, Moss says.

Moss has big goals for Dallas College. This year, the school’s sustainability office is focused on the first greenhouse-gas emissions inventory for the entire college district, as well as a report for AASHE. Then, the school will start working on its first district-wide climate action plan. When the school’s electricity contract is up for renewal in May 2021, Moss says, Dallas College plans to purchase 100 percent renewable energy and expects the school will be able to make the switch at the same or lower cost than what it pays for energy now. The school is also planning to launch a campaign called Renew Texas 25 to encourage other schools, businesses, and individuals to pledge to switch to renewable energy.

Since Dallas College is a commuter school, emissions from transportation make up a huge portion of its carbon footprint, Moss says. In the future, she hopes to collaborate with the city of Dallas to boost public transportation and make it a better option for more students.

Like Rice, many of the colleges have already focused on updating equipment and operation processes so buildings run more efficiently, Moss says. There are many examples of these initiatives, she says. The schools have an ongoing project to replace all lightbulbs with LEDs, and many roofs are now reflective “cool roofs,” to lower electricity consumption during the hot months.

University of Texas at Austin

While the University of Texas at Austin has a robust sustainability program, according to Dautremont, the school does not have a set carbon-neutrality goal or plan at this time. The school did recently finish an updated greenhouse-gas emissions inventory, which provides the baseline metrics necessary to create such a plan. The aim is to update the school’s sustainability master plan this fall, which may include goals around carbon neutrality, says Jim Walker, the university’s director of sustainability.

“We’ve been practicing energy efficiency and a commitment to that for a very long time, and we’re kind of pivoting along with a lot of our big public flagship peers into these other emissions conversations,” Walker says.

The university is essentially an energy island within the city of Austin because the school generates its power, heating, and cooling on campus from its own, highly efficient, natural gas plant. The plant is so efficient and cost effective that it will be difficult to replace. Plus, the university is so large and dense it could be challenging to install renewable energy on campus or source all the energy the school needs from renewable sources.

But in just the last year, climate change has become more of a priority for students. “There is a growing level of interest on this campus on our emissions footprint…. That’s a conversation that is, coincidentally with your story timing, kind of just emerging on this campus,” Walker says.

Similar to Rice and Dallas College, UT has a green building program for new construction projects. The natural gas plant is also an international model for efficient production of both heat and electric power, Walker says. And for some satellite facilities, like the Pickle Research Campus, the school buys renewably sourced electricity from Austin Energy, the city’s municipally owned utility.

Texas Christian University

Of these four schools, the sustainability movement at Texas Christian University (TCU) in Fort Worth is the most nascent. In the late 2000s, TCU was one of the early schools to sign a formal climate commitment. But in the years since, the administration did not maintain the commitment, for unknown reasons, says Becky Johnson, a professor of environmental science at TCU and chair of the school’s sustainability committee.

Sustainability has only recently become more of a priority on campus, Johnson says. In the last few years, more and more students have come to TCU from California and the Pacific Northwest, and those students have demanded increased sustainability efforts on campus, she says. In response, Johnson and her peers, who have long championed campus sustainability, petitioned the faculty senate to start the permanent sustainability committee that Johnson now chairs.

The job of the committee is to monitor sustainability efforts on campus, implement new programs, and communicate about campus recycling and other initiatives to students and faculty. Because the committee is still in the first two years of its existence, its purpose and responsibilities are still being finalized. While the school does not have a carbon neutrality commitment or goal at this time, Johnson is hopeful TCU will resurrect its climate commitment one day.

The committee has rolled out online resources including a Facebook page, as well as an on-campus marketing campaign to educate students and faculty about how they can adopt greener habits on campus.

+++++

Jillian Mock is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. Her reporting has appeared in the New York Times, Audubon Magazine, Popular Science and other publications.