Boquillas Canyon, Big Bend National Park in West Texas

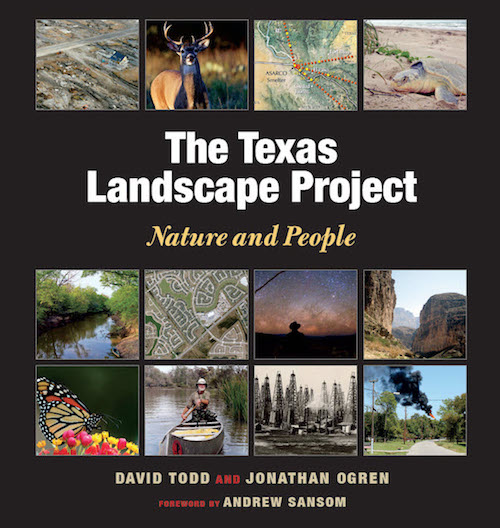

At nearly 500 pages, a new atlas called The Texas Landscape Project: Nature and People is as sweeping and varied as its title suggests. The large-format book, published recently by Texs A&M University Press, examines the state’s ecology and conservation history through 300 original maps, more than 100 photographs and thousands of words of text. Hundreds of cited sources comprise a guide for further reading and study.

Andrew Sansom, who heads the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University, writes in the Foreword that the volume is “a breathtaking compendium of insights into the natural history, the environmental richness, and the manifold conservation dilemmas confronting the Lone Star State today.”

Chapters cover dozens of diverse topics. Listing a few will indicate the book’s ambitious scope. Some discuss individual wildlife species – the desert bighorn sheep, the American bison, the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle and the monarch butterfly, for example. Others deal with landscape features such as the Big Thicket, Barton Springs, the Ogallala Aquifer and the Edwards Aquifer. Some deal with man-made developments and infrastructure, like reservoirs, the Trinity Barge Canal, dams in the Big Bend, and Texas-Mexico border colonias. Still others examine the impacts and implications of selected human activities – pollution in many forms, cooperation as an element in efforts to conserve land and wildlife, the production and use of coal, oil and natural gas. Others look at processes, natural and human-influenced, including drought, storms and land subsidence.

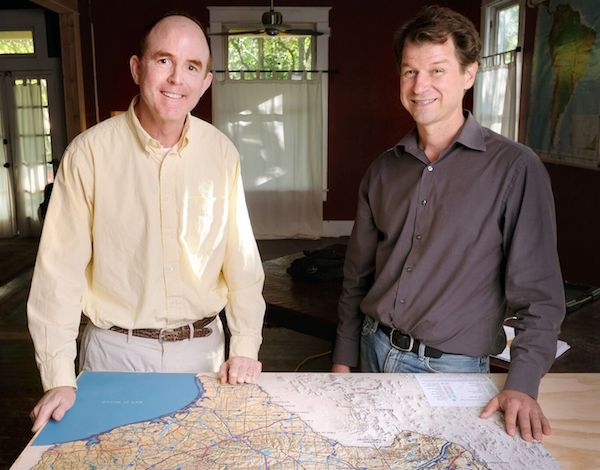

The book’s Austin-based co-authors are the writer David Todd, a veteran conservationist whose family’s conservation interests stretch back over three generations in Texas, and the cartographer Jonathan Ogren, founder of Siglo Group, a planning firm specializing in conservation and natural-systems work. They separately answered questions posed by TCN editor Bill Dawson. Following are lightly edited transcripts of those conversations.

(A companion website, texaslandscape.org, includes maps from the book and a calendar of upcoming events involving the authors.)

+++

David Todd

Tell me first about the Conservation History Association and how your work with that organization gave rise to this project. And related to that, why did you undertake this book? What were your principal aims?

I am the founder and the executive director for the Conservation History Association of Texas, which is a very small environmental education nonprofit based in Austin. It was started in 1998 and its purpose was to try to develop a video archive and later a book based on oral histories from various veteran conservation leaders from around the state. Ranchers, farmers, scientists, engineers, a journalist or two, politicians and a lot of activists and local organizers who were not only aware of environmental issues but were engaged in trying to improve and restore their part of Texas. The idea behind it was that this might be a way to get a vernacular, idiosyncratic, personal view of why conservation happens, how it is done, why sometimes it succeeds, why sometimes it fails, how people feel about it, really a subjective, experience-based view of conservation in the state. I think also a mortal view of it because, unfortunately, I’d say about a quarter of the people we interviewed have died. This stuff is highly perishable and we wanted to capture some of the people who had been doing this in the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s – at the very outset of when environmental laws and conservation laws and agencies were being set up and they could tell these origin stories. Very helpful to give us some background on the environmental challenges we have today because a lot of them go back years, decades, generations.

How did this current project emerge from those beginnings?

As we were saying, the original Conservation History Association of Texas program, which was called the Texas Legacy Project, and the related book, called The Texas Legacy Project: Stories of Courage and Conservation, were based on spoken word and they were oriented toward people’s subjective view of their lives. When we completed the book with Texas A&M Press, our editor, a woman named Shannon Davies, was kind to ask us if we’d consider doing a sequel. And I thought it might be good to explore doing not only a sequel, but the flip side of the original book. So where the first one was audio-based, this one would be more visual. And instead of being more subjective, personal views of conservation, this one would be Big Data-based, drawn from government and academic and nonprofit files, and would present a more geographic view. So instead of it being more personal it would be more place-based. So in many ways it’s related to the same stories about environmental history in the state but it’s taking a different view, one that’s more geographic, more objective, perhaps, more data-based.

The book covers an extremely broad range of subjects, to put it mildly. How did you choose them? Was there a culling that went on from an even longer list of potential subjects that you had in mind, and if there was, what were a few of the topics that almost, but not quite, made the cut?

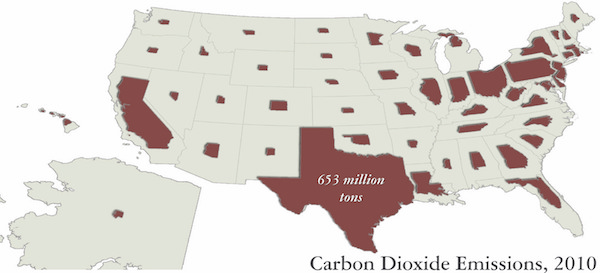

Well, we started off with five major categories of land, water, energy, wildlife and air quality. Then there was a sixth that it is more of a catch-all, and it’s called the built world. Within those six categories we have about 40 chapters. They range across the gamut. I guess about 20 possible chapters were left on the cutting-room floor. Sometimes, it was because it was an issue that we couldn’t get good data on. An example of that would be solar power in the state. A lot of the datasets about where these solar panels are installed are sealed for privacy issues because they tend to be panels on people’s homes. So I wasn’t able to get releases on that data. That was probably the biggest stumbling block. There were other issues, and I think climate change is a good example of this. For me at least, it was difficult to get a lot of historical data, even if it could be released. It seems, at least until the last 10 to 20 years, it’s been more of a prospective kind of concern and getting data that’s really incontrovertible and goes back a bunch of years was really hard. We found a few datasets. There are some interesting bits of information about how the [U.S. Department of Agriculture’s] hardiness zones have shifted north, which fits with what the climate models suggest. And we have a lot of data about factors in climate change — carbon emissions and ways to mitigate climate change, such as with wind power — but to get really definitive data about past changes in the climate, I just found it hard. A lot of this may be just limitations on what I know and what I can understand.

I did note that climate and climate change are treated in numerous places throughout the book under various chapters — coal, natural gas, sea-level rise and drought, of course, and others as well. Related to that and to what you’ve just said, I would just ask whether or not it’s the case that your decision not to make climate change a separate chapter in any way reflects your view that it’s not as important as these other things.

I think it’s the big kahuna [laughs], the big enchilada. I think there’s nothing more important than climate change. But I think it’s interesting how it’s been segregated as its own topic and I think its power and the fear that I have of it is that it’s so interwoven with so many aspects of our lives. You went through some of the examples there. There are aspects of how it affects our agriculture, aspects of how it affects wildlife, there are signs that it affects our water supply, signs that it affects coastal hazards, with tropical storms and hurricanes. It’s just woven through every environmental and economic and social issue I can think of. There was some conscious decision not to set aside a climate change chapter in part because it was difficult to get pure climate numbers that were historical. But also it seemed – there’s that wonderful quote from John Muir, let’s see if I can remember – “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” I think that having a stable climate or having one that’s starting to break down and do really volatile things is connected to almost everything else in our world.

Consistent with this being a project of the Conservation History Association, you of course take a long-range perspective in discussing and portraying many or all of the subjects in the book. In some cases, a really long-range perspective. I noted that the discussion of the bighorn sheep, for instance, talked about how it was under two and a half centuries of human pressure, which is a really long-range perspective to take. As someone who believes in the value of history, what is the value that you think a long-range view like the one in this book offers to the general reader who might not be as big a history fan as you are?

I think that we venerate things that have been around a long time. Our forefathers and foremothers. We erect a lot of statues in courthouse squares. And I think that we should recognize that a lot of the environmental values that we hold dear, and some of the conservation successes that we’ve seen, are the result of years and years and generations of people’s contributions. You think of the Big Thicket and how it took a good solid 50 years to set aside those acres in Southeast Texas. There was this long daisy chain of people who were concerned about this and carried on from one decade to the next. I think that ought to be honored. I hope that by showing that a lot of these stories go back years and years it gives them more credibility because they are something that appeals to people year in and year out. The conservation ethic is something that’s shared across many generations.

Andrew Sansom in his Foreword to the book notes that it’s not just a work of history but that it discusses, in his words, “the manifold conservation dilemmas” that face Texans as they move into the future, right now. After finishing this sweeping look at dozens of conservation issues in Texas, past and present, what would you say are some of the biggest dilemmas – other than climate, which you already talked about – that you see looming now and in years ahead for this state?

That’s a good question. There have been a lot of people who have talked about geologic time and the Pleistocene and the Paleocene and the Eocene [epochs]. Recently, our own age is the Anthropocene. [Editor’s note: “Anthropocene” is the proposed term for a new epoch, with dominant human influence on geology, climate and ecosystems.] I think that maybe the major dilemma is that we’re in charge now. The decisions that we make now are really consequential, not just for ourselves, but for the whole life support system for ourselves and for biota that we share the planet with. That’s a really daunting kind of challenge. There’s an interesting side-aspect to that. It seems that Texas is growing by leaps and bounds. Lots of population growth. Lots of economic development. And it occurs to me that there are two sides to that. One is that that puts a lot of pressure on the natural systems. We’ve got to find water to supply the people and their industries. We’ve got to build roads to get people around. You’ve got to develop farmlands and ranch lands to feed them, and so on. So there’s lots of impact from all this growth and development, but on the other hand, if this is truly the Anthropocene, then there are moral responsibilities that are going to fall on people to take care of the planet and Texas. And I think it’s also something that people can take responsibility for. We’re a really resilient and resourceful species, and there are oodles of examples throughout the book – and I’m sure you can think of lots that are not in the book – where folks have come up with really clever solutions where you have your cake and eat it too. Protect the planet and satisfy the things that we like to have.

Related to that, the next couple of questions on my list fit right with your response just now. After finishing this book, are you optimistic or pessimistic? Has your attitude or outlook changed as a result of this project? You knew a lot about these subjects when you went in and I suspect you know a lot more now than you did then. Are you an optimist or a pessimist now?

I have kids so I need to be optimistic. And I think there’s evidence to be optimistic. I’ll give you a couple of thoughts that have occurred to me a bunch of times. If you go back 30 or 40 years, you had the passage of all the major federal laws – the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Wilderness Act, the panoply of federal campaigns to try to protect the environment – then all the agencies that were set up. There was a real effort, but it seems to me it was a really institutional and regulatory effort that was sort of out there. It was somebody else that was going to fix these problems with laws and rules and money. And I think the encouraging thing I see happening is that individuals are taking more personal responsibility now for environmental protection. And they’re not assuming that somebody else is going to do this for them. Every time I see somebody drive by in a Prius, or when I go birding and see people tapping in the birds they’ve seen and sending the data to Cornell bird lab so that data can be recorded and used by researchers and conservationists. Or when I see folks putting those little labels on tiny butterflies to track where the butterflies may be going and understanding their protection. I just take a lot of heart in that – that folks are seeing a personal stake in conservation. That’s very heartening for me.

+++

Jonathan Ogren

Tell me about the Siglo Group and how your work with that organization really gave rise to this project. Why did you undertake this project and what were your principal aims in the role that you played?

I worked in the conservation and land planning field for a number of years, then I started Siglo Group because I was really interested in focusing on natural elements. We’re interested in helping folks integrate natural elements into land use and land-use planning. I got to work with David as a result of that. We worked on a number of projects, including some ranches. He was a funder on a large conservation project that was statewide. That relationship went well and he asked if I would be interested in doing a couple of templates on a statewide atlas. I said of course. As someone interested in spatial analysis, geographic information, layering of environmental issues and land use, it was a dream job. So we started with a couple of templates. They were well received and it blossomed into what is the Texas Landscape Project.

That relates to a question I had. For readers who may not know, what is GIS, which stands for geographic information science and sometimes geographic information systems? How did it factor into this project?

Usually GIS is geographic information systems. Out of that was spawned geographic information science. It is one of the first places where we’re using big data. Over the last two decades, there have been municipalities, federal, state and private entities, all collecting this information about where something is happening. If you think about your smart phone, when you go out and use it, it’s collecting location data, relevant to you, that helps you use it to get somewhere, or figure out where you might want to go to get the best coffee, or figure out what’s the best deal in your area. That’s all really part of GIS, or this renaissance of GIS. Why we might be interested in it is just as important as what it is. if you think about the room you’re sitting in now, you know how far the lamp is away from you, how far your keyboard is away from you. You can look at the doorknob and know how many steps you need to get over there to open it up with your eyes closed. We can go out on a street and understand it at block level. But when we start expanding how we’re thinking about space – like when we go to a city-wide space or the entire Brazos River watershed, or the entire Colorado River watershed, or we think about an entire eco-region like the East Texas Piney Woods or the Edwards Plateau, when we think about an entire state – it becomes much harder to think about cause and effect, to think about what’s causing an impact. What GIS allows us to do is stack up all the different layers — where flooding is happening, where the soils are more dense, where there’s more development going on, where subsidence is happening – and ask, what are the major drivers of the natural occurrences we’re seeing? What is impacting this particular site? By evaluating all those elements, whether they’re working on a state scale, a local scale or a regional scale, that’s where the power of GIS comes in. Another thing that’s really cool about GIS is we’re a visual species. We see an image and that allows us to process information in different ways than if someone’s telling it to us or we’re reading it. One of the outputs of GIS is maps or visual representations of space that allow us to better understand some of those scales that are hard for us to see when we’re walking around in the world.

I read in your biography that you worked previously with organizations including NASA and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Were there particular previous jobs or projects that influenced or helped inform this work in an especially notable way? I’m thinking in terms of technical particulars of a project you may have had – mapping for somebody else, say.

At NASA, I was just a young college student working in life support systems. For years and years, my goal – as an adolescent and then a college student – was to understand how you could create an ecosystem in a bottle. The idea of moving to Mars or anywhere else. I loved getting to work at NASA for a short time as a college student, but I realized there are so many unknowns about our own environment and our own ecosystem and this is such a complex structure, that was what I wanted to study. Getting to do something like the Texas Landscape Project is going back to that. What a great thing to be asked to do – would you like to look at spatial and geographic relationships throughout the state associated with environmental issues? The answer is an overwhelming yes.

Did the development of these maps open your eyes to some things about Texas, and conservation in Texas, that you had not been aware of before?

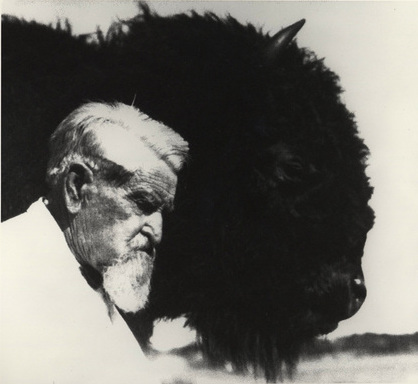

Absolutely. I learned all sorts of amazing things through this project. One of two that are really interesting to me is Houston and the subsidence issue. Starting from 1906 to around now, there are some parts of Houston that have sunk 10 feet as a result of pumping groundwater and other things out of the ground. To recognize that in Houston, one of the largest municipalities in the state, the ground has sunk 10 feet is an enormous issue. The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District has addressed that in the downtown area and they’re not seeing as much subsidence in that area, but it is still going on in the northwest area. It was a revelation to me to understand that, especially when you think about storm surge, flooding events in the Houston area, climate change and the potential of sea-level rise. It’s something that numerous people are thinking about in a critical way. The other one that comes to mind quickly is Charles Goodnight. [Editor’s note: Goodnight was a legendary Texas rancher in the 19th and early 20th centuries who was instrumental in preserving the American buffalo, or bison.] The portrait of him in the book is such a stunning portrait of an individual, with the bison. It’s a captivating photo, but also [the book’s discussion of] what the bison populations were throughout North America – Canada and the United States – compared to what they are now. They were almost extinct, but now there are a number of thriving populations and if that trend continues, we’ll have these massive bison herds going forward, maybe over the next 100 years. And that’s something exciting to think about – not only the work that someone did many, many years ago, but how it’s continuing, how it might continue into the future.

What’s your wish for people to come away from this atlas with, whether they read it from cover to cover or just browse in it or use it as a reference work?

Ideally, they find something that they already had interest in and get to learn more, or find out something new and intriguing and learn more about it. I would like to think that Texans love their landscape, and any chance we get to learn more about it will just enhance our appreciation of it. And the more we appreciate it, the more we’ll think about it as we’re making other decisions, and as a result it will be better protected or conserved for our generations to enjoy, plus future generations.

+++++

Disclosure: David Todd has donated financially to Texas Climate News, a nonprofit, tax-exempt organization. Andrew Sansom is a member of TCN’s Advisory Board and a member of the Board of Directors of the Jacob & Terese Hershey Foundation, which has provided funding to TCN. Our independent journalists make all editorial decisions regarding this magazine’s content, with no direction by donors or volunteer Advisory Board members.