In his nearly two years representing Texas Congressional District 21, Charles Eugene “Chip” Roy has established himself as a rock-ribbed conservative and enthusiastic supporter of President Donald Trump’s policies.

A member of the Freedom Caucus, an activist group comprising the most conservative Republicans in the House of Representatives, he has gained a reputation for championing conservative causes and tripping up legislation at odds with his political convictions. That includes an attempt to block passage of a bipartisan disaster-aid package for Hurricane Harvey damage.

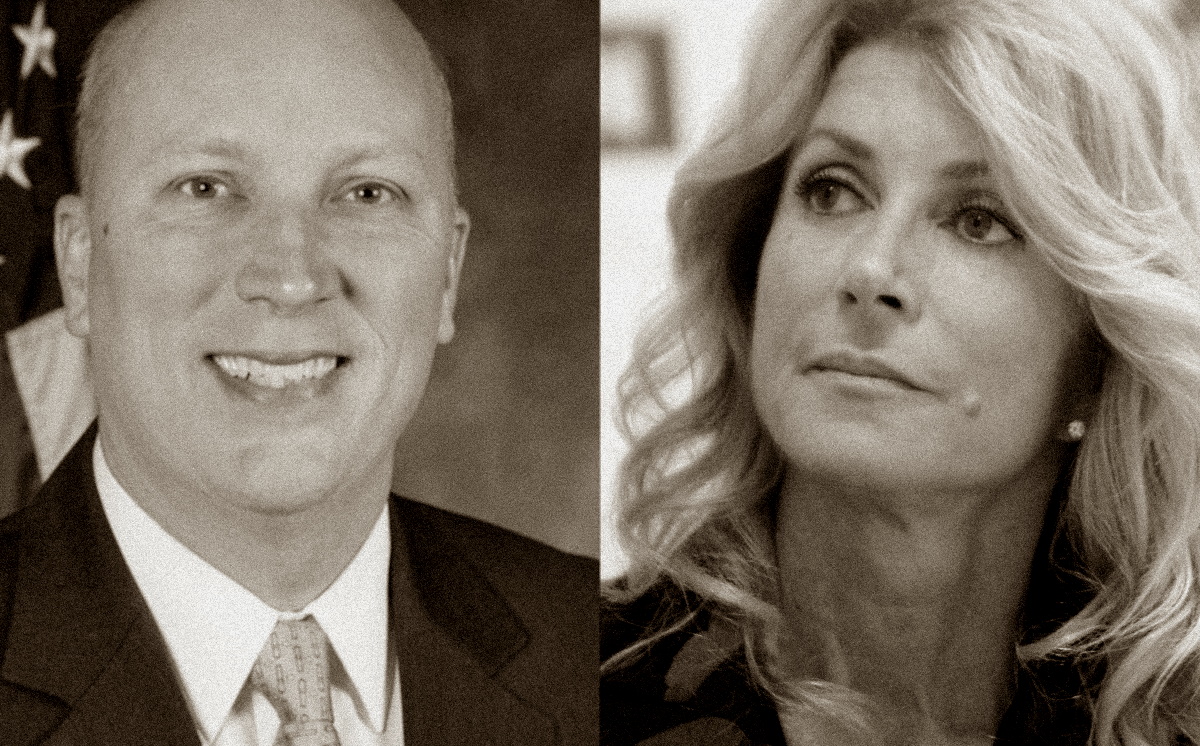

Roy, who faces a challenge on Nov. 3 from Democrat Wendy Davis, has uniformly sided with oil and gas interests on environmental issues. Also on the ballot are Green Party candidate Thomas Wakely, and Libertarian Arthur DiBianca.

Roy represents a region that is largely rural, white and Republican. Though the 21st Congressional District nips small bits of South Austin and northern San Antonio, it mostly balloons out in a westerly direction between those two cities, encompassing much of the lightly populated Texas Hill Country.

An attorney, Roy’s resume includes work for Republican U.S. Sen. John Cornyn and former Texas Gov. and Energy Secretary Rick Perry, as well as serving as U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz’s chief of staff and then first assistant Texas attorney general under Attorney General Ken Paxton. He packed his bags for Washington, D.C., after defeating Democrat, scientist and Army veteran Joseph Kopser in the 2018 mid-term elections.

The district was previously represented by another conservative Republican, Lamar Smith, from 1987-2019. Smith earned a national reputation as a climate-science denier when he was chair of the House Science Committee for his tireless efforts to discredit the vast scientific consensus about the dangers of manmade climate change.

The 2018 race between Roy and Kopser offered a stark contrast, with Roy echoing Smith’s contrarian climate views. Roy told the San Antonio Express-News that he agreed with Smith about “the hysteria about climate change” and said “I don’t know” whether there is any connection between human pollution and climate change. Leading scientists say people are, in fact, the main cause. Kopser accepted climate science and promoted the district’s potential to be “a leader in this future economy” of renewable energy.

After Smith’s string of victories in election after election, Roy’s win was not a surprise. What did raise some eyebrows was Roy’s margin of victory – 50 percent to 48 percent – thin enough to give Democrats hope that Davis might have a shot at unseating him in 2020. Polls show Davis and Roy in a virtual dead heat, with Davis trending slightly upward.

Mark Jones, a political science professor at Rice University, has noted that President Trump’s presence on the ballot could give Democratic candidates a boost by “dragging most Texas Republicans down,” owing to the president’s polarizing behavior and consistently low approval ratings.

Davis is also an attorney who at first glance may appear to be Roy’s political opposite. Initially a Republican, Davis served for nine years on the Fort Worth City Council but later, as a Democrat, became widely known as a progressive firebrand after her highly publicized 2013 marathon filibuster to block Senate Bill 5, which sought to tighten Texas abortion restrictions. (The bill ultimately passed.)

The issue was a personal one for Davis, who had struggled to make ends meet as a young, single mother. But her longtime friend Joel Burns, who succeeded Davis on the council and describes her as “whip-smart – one of the smartest people I’ve ever met in my life,” says that single moment in time has typecast Davis as one-dimensional and uniformly liberal, an oversimplification that is not accurate, he says.

“She comes from a business background. She is a businesswoman at heart,” Burns said. “She ran a title company, and she had her own law practice. Wendy is actually a fiscal conservative with some progressive values.” Those penny-pinching principles were often on display during her City Council and state Senate tenures, he said.

Following her council stint, Davis defeated incumbent Republican Kim Brimer for the 10th Senate District seat in 2008. She served two terms before unsuccessfully challenging Greg Abbott for governor in 2014.

While some of her political positions, including a goal of making the country carbon-neutral by 2050, may seem an odd match for the reliably Republican 21st Congressional District, Burns believes Davis’ balance-sheet sensibilities and demonstrated willingness to reach across the political aisle give her a solid chance to win.

“I actually think Wendy is a good match for what the district is, and what it’s becoming. In addition to being a fiscal conservative in her heart, she’s progressive on issues that are important to people’s day-to-day life. I don’t think that’s out of step with the district she would represent,” Burns said.

Roy’s campaign website is heavy on law-and-order and fiscal-restraint issues, light on environmental positions. However, while he emphasizes the economic importance of the Texas oil and gas industry, Roy acknowledges renewable energy as part of a broader solution.

“We can responsibly address environmental concerns and maintain low energy costs by pursuing a comprehensive policy of energy production that focuses on low-cost, abundant, clean energy options – including natural gas, oil, nuclear and renewables,” Roy states on the website.

“A competitive marketplace of ideas that does not restrict investment in specific industries will ensure that the United States is prepared to meet the economic and environmental issues of the future.” Yet, Roy scores zero on the League of Conservation Voters’ National Environmental Scorecard, having cast what the organization deemed to be 29 “anti-environment” votes during his tenure.

Davis, by contrast, sees climate change as an existential threat that demands an aggressive response. “Anyone who isn’t urgently working to address it is failing our responsibility to our kids and grandkids. When I think about the world we are leaving for my grandchildren to inherit, I feel an extraordinary commitment to them,” she states on her campaign website.

“I want to be able to tell them that I did my part to assure they will live in a world that can sustain their children and grandchildren.”

A transition from fossil fuels to renewable-energy sources will cause economic pain for an oil-and-gas state like Texas, but will be unavoidable, says Andrew Waxman, assistant professor of Public Policy and Economics at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas.

“It’s pretty clear that the costs of climate change are starting to be borne now, and that they are going to intensify, so the debate among scientists and climate models is really about how rapidly and intensely are they going to compound,” Waxman said.

“I think there’s probably a pretty strong case to be made that if we want to stem the tide on climate change in any realistic sense, we may have to make investments beyond the point that they’re just financially viable. That is to say, even if in the short run they don’t have a sufficiently high rate of return, we may need to make them so that over the long run we mitigate long-term costs.”

Waxman notes that even though the very phrase “climate change” is met with political resistance in the state, there is “a lot of thinking” going on among Texans and Texas politicians about how to address it. “I think that not making smart policy choices with regard to climate change has its own specific set of costs for Texas,” Waxman said. “My hope is that we can come up with solutions to address these challenges.”

+++++

John Kent is a contributing editor for Texas Climate News.