Eminent domain, imminent video: Julia Trigg Crawford (foreground) says Keystone pipeline crew members on her Northeast Texas farm would train a video camera on her whenever she photographed their work.

By Greg Harman

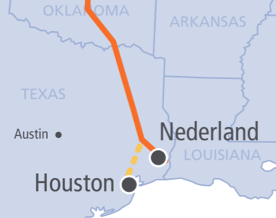

When TransCanada came to Texas to build the southern leg of the Keystone pipeline to transport Canadian tar-sands oil from Cushing, Okla., to refineries in the Houston and Beaumont-Port Arthur areas, they met resistance at nearly every turn.

Motivated climate activists, concerned about that oil’s especially high carbon content, camped out in trees in the pipeline’s path, chained themselves to earth-moving machinery, and even buried themselves in the pipeline itself.

But one of the company’s most formidable foes proved to be a third-generation farmer whose conservative roots and property-rights message garnered a sympathetic hearing from across the media spectrum, including Fox News, an outlet not known for its environmental sympathies.

While Julia Trigg Crawford learned to work closely with climate activists employing civil disobedience to stop the movement of the tar-sands-derived oil – and was herself arrested at a protest outside the White House in 2011 – she didn’t allow such tactics on her 650-acre farm while fighting TransCanada’s use of eminent domain to seize Crawford land for its pipeline.

“That doesn’t play in Northeast Texas,” she told Texas Climate News recently. Keeping her fight within the bounds of what’s legal and in the court of public opinion enabled “anybody to get on the bus” to support her, she said. Her farm is located a few miles outside Paris, about 100 miles northeast of Dallas.

+++++

Reader-supported journalism: This article was made possible

by conributions from TCN readers. Please consider making a donation.

+++++

Crawford is just one of a growing number of recently minted rural activists with potentially invaluable lessons for members of the state’s established environmental organizations hoping to advance their agenda during the 84th Legislative session in 2015 in spite of strong tea party wins in this year’s Republican primary. Those primary results are expected to translate in November into yet another rightward shift in an already conservative lawmaking body – a change that will be magnified if state Sen. Dan Patrick, a very conservative Houston Republican and tea party favorite, becomes lieutenant governor and therefore presides over the Senate.

“It will be one of the most conservative legislatures we’ve ever seen, and we’re going to make a tremendous change in the way we message,” said Tom “Smitty” Smith, for many years the Texas director of Public Citizen, a national consumer-rights and environmental advocacy organization.

To start crafting that new message, members from more than a half-dozen environmental groups hosted a “priorities conference” in Austin on April 5. Longtime, mostly urban, environmental organizers traded ideas with kindred spirits from emerging, rurally rooted pockets of resistance to pollution and other environmental woes.

Most of these newer voices relayed stories of personal hardship. One man told about fighting to keep his 800-acre property from being flooded by the planned, multi-billion-dollar Marvin Nichols Reservoir in Northeast Texas. A former pecan farmer said he sold all his equipment and went out of business after experiencing vastly reduced yields and aggressive rust damage he blamed on fallout from the nearby Fayette Power Project, a coal-fired electric plant east of Austin. A Harris County resident said his family began developing major life-threatening illnesses after moving, unwittingly, close to the San Jacinto River Waste Pits, a federal Superfund site near Baytown.

“You think you can move out into the country and enjoy yourself. That’s just not the way it works,” Calvin Tillman, former mayor of DISH, a tiny town in North Texas that’s named for a satellite-television company, told the group in an overview of eminent domain practices in the state. “You’d think this stuff happens in Connecticut or California, that it can’t happen here in Texas. This is a property-rights state.”

Tillman grew up in the Oklahoma oil patch and considered himself one of the most industry-friendly city commissioners when he was first elected to office, but his relationship with the natural gas industry – in particular, those companies engaged in hydraulic fracturing, the drilling method better known as fracking, in DISH – grew increasingly tense after his children began to experience frequent nosebleeds and breathing difficulties.

DISH residents complained to company officials about noise and odor issues that followed the construction of a large compressor station, pipelines, storage tanks, and drilling of more than 50 wells in, and immediately around, the town of just more than 200, only to be rebuffed, Tillman said.

“They were like, ‘We’ll put up sound walls when the court says we have to put up sound walls,’ you know? ” Tillman said. “That was the thing that angered people the most. They just wouldn’t work with us at all. They treat you with such indignity and disrespect.”

The largely Republican town soon learned how little power it had to force the companies to change. Investigation by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has failed to substantiate the findings of at least one independent study raising public health concerns about industry emissions. A lawsuit brought by the town against six of the so-called “midstream” companies operating compressor stations and pipelines there is still pending in state district court.

[However, last week a Dallas jury awarded a ranching family living roughly 25 miles northwest of DISH a $2.95-million civil verdict for injuries sustained from fracking operations there. In an echo of complaints long made in and around DISH, the family claimed air, land, and water pollution linked to the drilling and production activity were behind “migraines, rashes, dizziness, nausea and chronic nosebleeds,” as well as the deaths of pets and cattle, according to Al Jazeera America.]

Tillman wound up resigning as DISH mayor and moving away in 2011 to protect his family’s health, he said. “They basically condemned my land and made it so I could never use it without ever setting foot on my land,” Tillman said of the recurrent noise and odor issues.

Eminent domain is a frequent tool of pipeline construction companies in Texas, requiring little justification under state law other than proof that an applicant is a “common carrier,” serving the public good by transporting its own product as well as competitors’. Critics say private companies’ frequent utilization of eminent domain – which involves seizure of property for the public benefit and is normally reserved for government entities – contradicts the state’s otherwise strong devotion to private property rights. They see this as an inconsistency in need of reform – something that state Rep. Rene Oliveira (D-Brownsville) tried unsuccessfully to accomplish in the last legislative session in 2013.

But air and water pollution also constitute public takings, argued Tillman and others gathered in Austin for the strategy conference.

“I talk about [fracking] emissions as a trespass on your property,” Sharon Wilson told the gathering.

Wilson, who worked in the oil and gas industry for more than a decade before becoming a dogged critic of fracking practices in North Texas’ Barnett Shale region, joined the advocacy organization Earthworks as its Gulf Region organizer in 2011.

“Air pollution and water pollution doesn’t stop at Republican homes. It doesn’t know if you vote Republican or Democrat or what. Everybody is affected,” she told Texas Climate News in a telephone interview before the conference. And while many still don’t know much about fracking beyond what they may see on television, oftentimes in the form of paid advertising, there is a “leveling action” at work, according to Wilson. That is simply the expansion of fracking itself. “As they expand, more opposition is created,” she said.

Political conservatives, many of whom are typically seen as unresponsive to traditional environmental messaging, tend to organize on environmental issues only when they are directly impacted, Tillman and Wilson agreed.

[Related story: Slaying “dragons of inaction”: A psychologist’s take on communication for climate action]

Oil began flowing through the Gulf Coast segment of the Keystone pipeline project – the leg from Oklahoma to Nederland, Texas, near Port Arthur – in January. An extension to Houston was expected to be completed this year. The Canada-t0-Nebraska part of the project –the Keystone XL pipeline – awaits U.S. government approval.

“The position we took [on the Keystone pipeline] is that a foreign corporation, building a for-profit pipeline, providing zero proof [they’re] for the public good, should not have the right to step in a take your land – whether it’s blighted or not,” Crawford told the gathering.

While the courts weren’t swayed – the leg of the pipeline from Oklahoma to the Texas coast became operational in January, though an appeal by opponents is pending before the state Supreme Court – it’s a message that resonated with neighbors near and far.

To date, Crawford said she has raised more than $120,000 for her fight against TransCanada.

“What’s really gotten people behind me is, here’s this lone farmer, and I don’t think it hurt that I’m a woman, and I’m willing to stand up in spite of all the odds,” she said outside the Unitarian church that hosted the conference.

Condensing the meeting’s message from a property-rights angle, Public Citizen’s Smith, based in Austin, asked: “The fundamental question is, what right do they have to trespass on our land and take our land and our air and our water?”

Another question, unspoken at the meeting, may be: What is the staying power of the Texas environmental movement’s newest members?

Organizers of the conference said beforehand that their aim was “to find consensus positions across partisan lines on eminent domain, climate change, hydraulic fracturing, water supply, electricity needs, and chemical safety issues to develop a list of priorities for the 2015 legislative session.” Based on follow-up communications and perhaps also ideas collected at gatherings around the state, meeting participants plan to develop specific policy recommendations for next year’s legislative session.

Tillman, who left the Republican Party as well as DISH, has since helped found ShaleTest, a nonprofit organization specializing in testing air quality for lower-income families and communities impacted by natural gas development.

Crawford is hard at work planning a grassroots resistance campaign called Texas Pipeline Watch, dedicated to keeping the pressure on operators of three Texas pipelines for Canadian tar-sands oil.

“I am not done,” she told the group plainly. “I’m just a hard-headed Aggie.”

+++++

Greg Harman is an independent journalist based in San Antonio. He was editor of the weekly San Antonio Current from 2010-12 and a staff writer for the Current from 2007-10. His writing has also appeared in publications including the Houston Press, Houston Chronicle, Dallas Morning News, Guardian UK, Texas Observer, Austin Chronicle, Fort Worth Weekly and Odessa American. His work has been honored by the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies, Houston Press Club, Society of Professional Journalists, Associated Press Managing Editors and others. Links to a selection of his work can be found at Harman on Earth.