Once upon a time, in a place called Texas, lawmakers of both political parties worked together with common purpose to tackle a problem known as climate change.

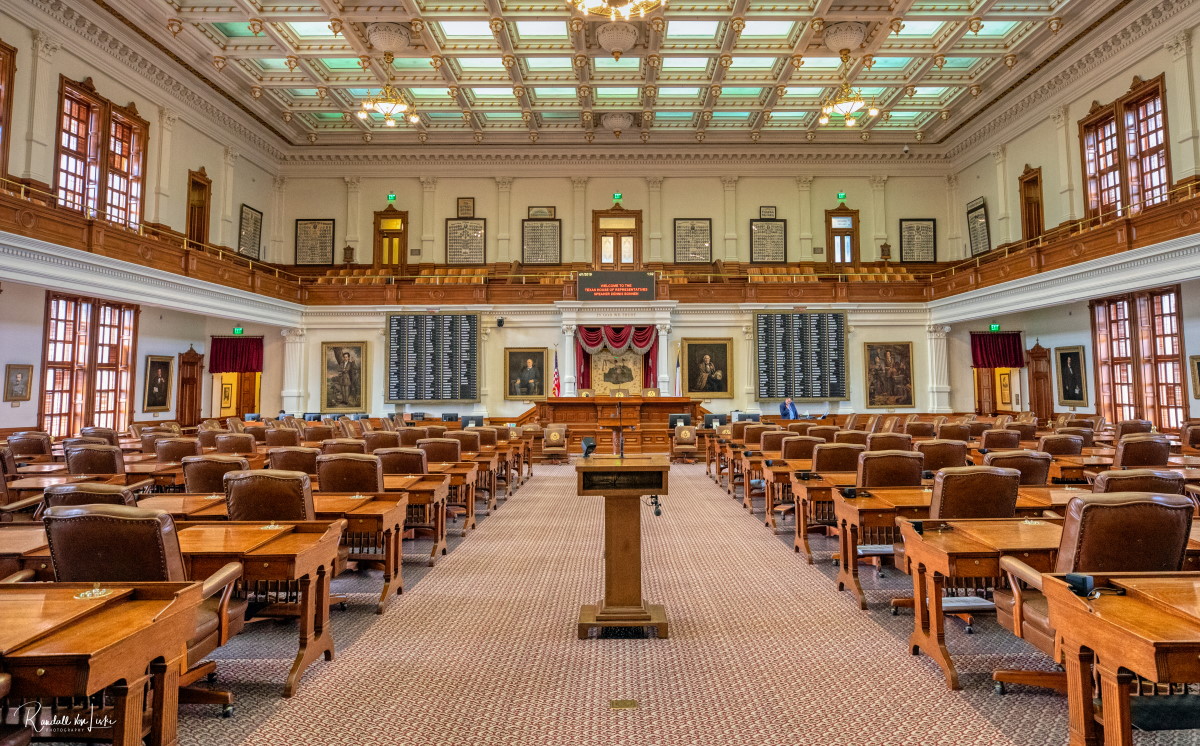

This is no fairy tale, as fictional as it might sound today, in the fiercely partisan, highly polarized politics of climate and energy. In 2009, in this real-life world where scientists urgently warn that pollution is dangerously deranging the climate system, a promising bipartisan effort to address the issue began to unfold in Austin at the Texas Legislature. No kidding!

The initiative fell just short of success, however. Various political factors that made adoption of climate-action and clean energy measures a strong possibility then had long since dissipated by the most recent legislative session a decade on. That latest session in 2019 ended with yet another long roster of failed bills, reinforcing the Legislature’s decade-long record of essentially doing nothing to deal explicitly with climate change and doing little to address it even implicitly.

This year’s election may well change that. Democrats, with many legislative candidates running on climate-action and clean energy platforms, are optimistic about picking up more House seats or even winning outright control of that chamber for the first time since 2002.

The House Democratic Caucus recently released what they’re calling the Texas Climate Plan, to be proposed in the 2021 session. More surprisingly, there are signs that Republicans, who have blocked such bills for years, could be sensing a new political atmosphere that may persuade some of them to back proposals that would reduce greenhouse pollution.

“Clean energy will be something that will advance this time, in this session,” predicted Jim Marston, a spokesman for EDF Action, the advocacy arm of the Environmental Defense Fund, and the recently retired head of EDF’s operations in Texas.

Marston, with decades of experience trying to replace polluting energy sources with cleaner alternatives in Texas and beyond, said if pandemic-related constraints allow the Legislature to conduct enough business, there are two basic factors pointing toward the likely success of clean energy proposals.

“There’s no doubt that Democrats will pick up some seats, and many are running on clean energy,” he said. In addition, “Republican pollsters have told Republican members that a very good issue for them to grab onto and support is clean energy. This is particularly true in suburban districts that now are clearly swing districts.”

Marston said he expects the session to see “a lot of activity, a broad range, everything from new incentives for clean energy projects to money for colleges and universities to train workers for clean energy jobs.

“I’m not saying that every issue will have bipartisan support and that lots of people will pass lots of things. But I do think there’s a convergence, with Democrats having more clout than they’ve had and Republicans looking for issues with suburban appeal.”

Actually passing bills through both the House and Senate to the governor’s desk will face formidable obstacles next year, if it’s even possible. Republicans will still control the Senate, where Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick will preside. But if Marston is right, the 2021 session could present the best chance for substantive climate and clean energy action since the 2009 session that was such a disappointment for proponents of such measures.

There was even a bipartisan “carbon caucus” that year, headed by one of the Legislature’s most famously conservative Republicans, former state Rep. Warren Chisum of Pampa in the Panhandle. With Chisum in that coordinating role, it looked as if Texas, oil capital that it is, was truly gearing up to take on the climate challenge.

That prospect was wholly consistent with the outcome of the recently decided 2008 presidential election. The winner, Barack Obama, and his Republican opponent, John McCain, both ran on pledges to enact closely similar regulatory proposals to reduce greenhouse emissions from industrial sources. It appeared that Texas officials, whether they liked it or not, might just adapt to the new Obama administration’s climate-action agenda, much as Texas leaders had adapted to other federal environmental initiatives in the past, despite their anti-regulatory, pro-industry qualms or opposition.

As the 2009 Legislature convened in Texas two months after Obama’s victory, hopes were high for various bills, such as measures to factor climate change into water planning, study ways to reduce emissions, and give solar energy the same statutory boost that lawmakers had historically provided to wind power in a 1999 mandate. That measure helped make Texas the top wind-energy state.

But most of the 2009 bills, even some that moved well along in the legislative process and seemed destined for success, fell short of passage. Many simply ran afoul of the constitutional time limits imposed on Texas’ every-two-years legislative sessions.

Climate-action and clean energy advocates were again optimistic in the next session in 2011, but at the end of the day, it was a similar story. Their hopes were dashed again as bill after bill failed to pass despite encouraging political factors that were in play.

A Democratic resurgence

Since that session, the chances of bipartisan climate action plummeted nationally and in Texas as climate and clean energy issues became increasingly polarized. Notably, pollsters recorded decreased acceptance of climate science and lower support for climate action among Republicans. Associated developments in Texas included the success of the Tea Party movement in moving the party further to the right and a series of rhetorical and legal attacks on climate action and climate science by leading Texas Republicans. They included former Gov. Rick Perry, former Attorney General (now Gov.) Greg Abbott, U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz and former U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith, who headed the House Science Committee.

The expectation by Marston and others that Democrats will make gains in this year’s state House elections is grounded in 2018 election results and in this year’s polling, both of which suggest Texas is quickly becoming a more competitive state after years of Republican dominance. Democrat Beto O’Rourke lost to Cruz in 2018 by only 2.6 percent, the smallest margin in a U.S. Senate race in Texas since 1976. Democrats won 12 Texas House seats held by Republicans that year, which carved Republicans’ House margin to 83-67.

On top of that, recent polls indicate the presidential contest is essentially a tossup in Texas after years of big winning margins for Republican nominees. Joe Biden led Donald Trump by 48 percent to 45 percent in a survey released Sunday by the Dallas Morning News and University of Texas at Tyler. A New York Times and Siena College poll released Monday had Trump ahead by 47 percent to 43 percent.

Democrats need to hold on to the 12 seats they won from Republicans in 2018 and flip another nine Republican seats to seize the House. Both parties clearly regard the battle as highly competitive.

Forward Majority, a national Democratic super PAC, announced in early September that it was giving $6.2 million to the party’s Texas House effort. The national Republican State Leadership Council, which works to win or keep control of state legislatures, raised $5.3 million to blunt that spending. Then last week, Forward Majority said it would double its Texas spending on House races to more than $12 million.

National Democratic and Republican groups are keenly interested in the Texas Legislature because census-based redistricting of congressional seats, a process conducted every 10 years, will take place in the 2021 session. The outcome of Texas redistricting will have national implications.

As always, various issue-specific efforts are being waged as part of the fight for House control, including initiatives to advance climate and clean energy action. O’Rourke, for example, is helping Democrats try to win the House with “An Open Letter on Climate to Texas.” In it, he explains the Legislature’s important role in addressing climate and energy issues and calls for the defeat of 10 specific Republican House members.

“State legislatures are key to solving climate change – they can spark clean energy innovation, ensure environmental justice, and hold illegal polluters accountable in our efforts to create clean air,” he wrote.

The letter singles out and critiques “ten of the worst climate voters in Texas (who) are running in flippable districts,” and promotes their Democratic opponents.

Campaigning on climate

Two Houston-area races – one of them on O’Rourke’s list – illustrate some of the ways that climate and energy are part of the election dialogue this year.

In Houston’s House District 134, which includes the sprawling Texas Medical Center and affluent inner-Houston neighborhoods, five-term Republican incumbent Sarah Davis is facing Democrat Ann Johnson, who ran against Davis unsuccessfully in 2012.

The district includes a lot of Democratic voters. Hillary Clinton beat Trump there by 15 points, and O’Rourke won 60 percent of the district’s votes in his narrow statewide loss to Cruz in 2018. Davis has consistently demonstrated strong crossover appeal, however, especially with her record as the only pro-abortion-rights Republican in the state House and positions on women’s health issues in general.

Johnson and her supporters are trying to erode Davis’ Democratic support in part with an attack on her climate record. That includes highlighting her vote that helped defeat a 2015 bill that might appear to be nothing more than an innocuous planning effort for better government. The unsuccessful measure that earned Davis’ no vote would have required the Texas state climatologist to produce climate projections for state agencies’ use in their strategic planning. The state climatologist is a scientist at Texas A&M University, appointed to the climatologist position in 2000 by Republican Gov. George W. Bush.

O’Rourke described District 134 in his “Open Letter” as “one of the most flooded in the state,” and Johnson’s campaign website stresses the link of increased flooding to climate change. The site has a dedicated page headlined “Counter climate change and mitigate flooding.” It outlines her pledge to “mitigate flooding, counter climate change, invest in clean energy (and) protect us from hurricanes” and criticizes Davis’ action and inaction in these areas.

Davis’ own campaign website proclaims her record and positions on issues in four areas – “advocate for women and children,” “fighting for victims,” “improving education” and “ethics and government accountability.” The words “climate,” “flooding” and “energy” do not appear on the site, according to a Google search.

In another Houston-area race – House District 29 in Brazoria County, with both populous Houston suburbs and rural areas – Democrat Travis Boldt is challenging incumbent Republican Ed Thompson. Boldt decided to run largely because of Thompson’s climate record, Boldt’s campaign manager Rish Oberoi said.

Boldt was disappointed that several climate-related bills were not scheduled for hearings or votes in the House Environmental Regulation Committee, where Thompson was vice-chair, and that Thompson would not acknowledge at a town-hall meeting that scientists have concluded climate change is mainly manmade, Oberoi said.

In a website video warning that climate-change threats including storms, fires, sea-level rise and crop losses are among the largest challenges ever faced by the U.S. and Texas, Boldt promotes “free-market solutions” to achieve a “carbon-neutral society” through actions like harnessing agricultural resources. Climate-action advocates urge more use of farm and ranch lands as “sinks” to remove and hold planet-warming carbon dioxide from the air.

Thompson was first elected to the House in 2012 and has demonstrated broad appeal in the ethnically diverse district. He easily defeated Democratic candidates in 2012 and 2016 and faced no Democratic nominee in 2014 and 2018.

In Thompson’s case, seeking support across party lines includes his performance on environmental concerns. Earlier this month, he received the endorsement of the Environment Texas organization as an “environmental champion,” becoming one of only two Republicans among the group’s 14 endorsees in Legislature races.

Thompson “has helped shine a light on lax enforcement by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality,” Environmental Texas said in the endorsement. “He is one of the biggest advocates in the Legislature to better regulate landfills and to promote recycling.”

On his website’s issues page, under the heading of “responsible environmental leadership,” Thompson stresses his work to improve air quality at a landfill and his commitment to “making sure our water, oil and gas, and energy policies are built with a growing population and growing needs in mind.”

The website includes no discussion of climate change or clean energy, but does note his leadership in the creation of a new Flood Infrastructure Fund.

Whoever wins in these and other races, Democrats will attempt to sharpen House members’ focus on climate and clean energy proposals with the House Democratic Caucus’s Texas Climate Plan and an associated Modern Infrastructure Act, announced at the same time.

The Climate Plan “includes targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, disaster resilience strategies, a timeline to end routine flaring at oil and gas wells and planning to ensure a just transition for impacted workers,” the caucus said in a statement when it unveiled the proposals. “The Modern Infrastructure Act will include investments in electrical grid capacity and resilience, electric vehicle charging stations, battery storage, electrification of mass transit, and bridging the digital divide.”

Passing such measures won’t just require Democrats winning control of the House or taking enough extra seats there to persuade their Republican colleagues to join them in passing clean energy legislation. The state Senate will have a Republican majority once again, with Patrick controlling that chamber’s work in his powerful role as its presiding officer.

An environmental lobbyist in Austin told Texas Climate News that Patrick is repeatedly making it “super-clear” that no legislation will move through the Senate except for bills dealing with “top priorities” such as budgetary and health-related matters. The Dallas Morning News reported in September that the Senate “appears likely to press for a slimmed-down agenda, given uncertainty about safety during the pandemic.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is founding editor of Texas Climate News.