Al Nelson of Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service inspects a drought-stricken cornfield in the Brazos River Valley in 2011. (Source: Texas A&M AgriLife)

Stewart Doreen, managing editor at the Midland Reporter-Telegram, captured the zeitgeist of a bleakly parched autumn with his lead for a November 15 article: “Sometimes, it feels like it’s not going to rain again in Midland.”

It did rain again in Midland – nearly a half inch on Thanksgiving weekend – but the West Texas city still ended up with one of its driest autumns on record. A mere 1.34 inches of moisture fell from September through November.

Texas as a whole just saw its 16th-driest October in 126 years of recordkeeping, and the period from January to October was the state’s 10th warmest year-to-date on record.

There’s likely to be plenty more mild weather, but only scant precipitation, in the upcoming winter across Texas. The main culprit is La Niña, a semi-cyclic phenomenon in the tropical Pacific that’s expected to prevail at least through the winter and perhaps longer. La Niña favors warm, dry winters across the U.S. Sun Belt, including Texas.

“We usually get a few very strong cold fronts, but with a lot of mild weather in between,” said Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon in an email, describing the prototypical La Niña winter.

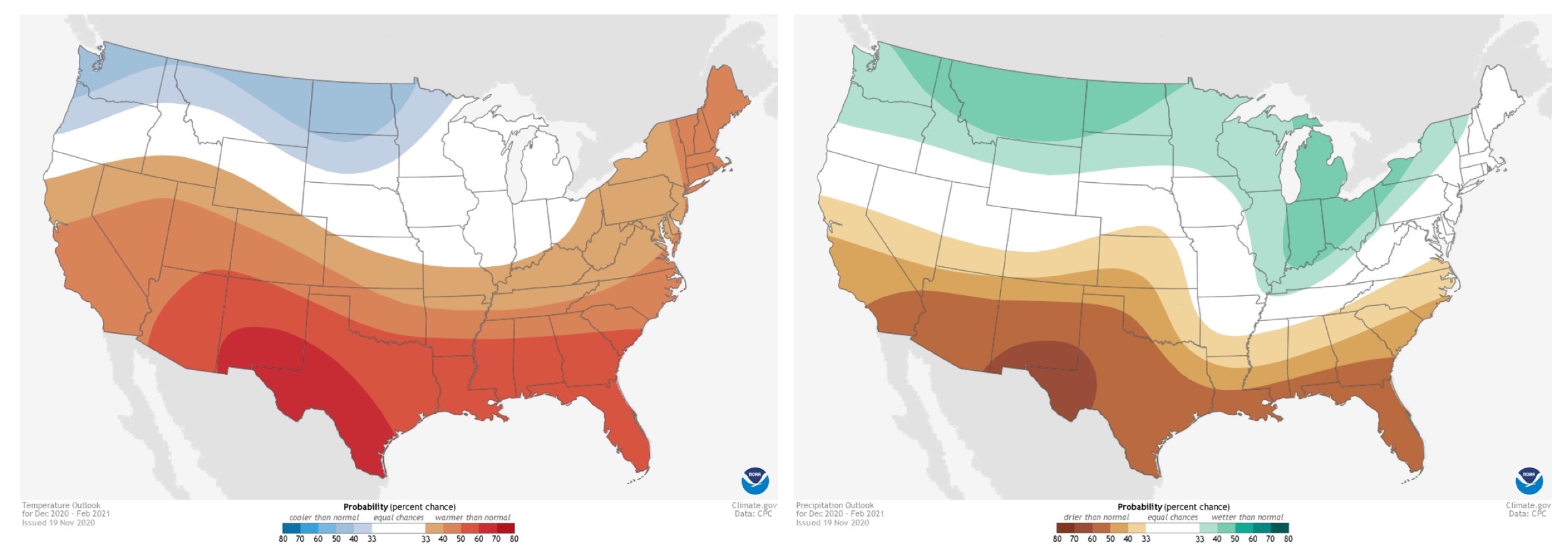

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s latest outlook for the period from December 2020 through February 2021, issued in mid-November, calls for enhanced odds of a winter that’s warmer (left) and drier (right) than usual across the southern U.S., including Texas. The outlook is in line with conditions that tend to prevail during La Niña. Darker colors denote greater odds of a given outcome. (Source: NOAA/Climate Prediction Center)

As of November, La Niña conditions had strengthened to levels unseen since 2011. That’s when Texas endured its driest water year (defined in Texas as the 12-month period from October through the following September) in more than a century of recordkeeping. The state averaged just 10.86 inches of moisture from October 2010 through September 2011.

That year’s fire season – the worst in modern Texas history – took 10 lives and consumed more than 2,900 homes.

Another strong La Niña event was in place from 1954 to 1956, during the peak of what NPR’s John Burnett called “the drought against which all other [Texas] droughts are measured.” The 1955-56 water year saw a mere 13.38 inches of moisture, the second lowest on record behind only 2010-11.

There are a few exceptions: the La Niña winter of 2011-12 was wetter than usual. “So while the odds are about three in four [of dry La Niña conditions] it’s not a guarantee,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

Most of Texas is already mired in drought, according to the weekly update of the U.S. Drought Monitor released on Dec. 3. More than 20 percent of the state fell into the two most dire categories: extreme or exceptional drought. The latest U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook from NOAA, issued in mid-November, calls for drought to either develop or persist across all but the southeasternmost sliver of Texas through February.

To make matters worse, rising temperatures from human-induced climate change can accentuate the impacts of a given drought. During hot weather, moisture evaporates from the landscape more readily. In turn, the drier landscape can then heat up further. The increasing prevalence of “hot drought” has been implicated in California’s recent plague of catastrophic wildfires, particularly those in autumn.

In Texas, the summer of 2011, which fell midway through the last major La Niña event, was not only the driest but also the hottest ever recorded, according to Nielsen-Gammon. At least three studies found evidence that human-caused climate change made the 2011 heat more likely.

Perhaps surprisingly, amid the wrenching flood years and drought years that are all too familiar to Texans, the state’s long-term precipitation average has actually risen by about 10 percent over the past century. However, statewide temperatures have climbed by more than 1 degree F at the same time. That’s acted to intensify the impact of the inevitable dry periods while also helping to make the heaviest rains, such as those in Hurricane Harvey, even more torrential.

Incoming: A heightened fire threat for much of Texas

The lightning-ignited Smith Canyon Fire in Pecos County in West Texas burned an estimated 11,000 acres in September. (Source: Texas A&M Forest Service)

“Our experience with past La Niña fire seasons has us anticipating a very active winter/spring fire season,” warned Brad Smith, head of predictive services at the Texas A&M Forest Service, in an email.

Outside of irrigated croplands, the West Texas landscape is now covered by stunted grasses and shrubs, the legacy of grazing and harsh dryness this summer and fall. Ironically, the sparsity of grass fuel will help tamp down the region’s vulnerability this winter outside of the worst bouts of fire weather, if only because there’s less to burn.

A bigger fire threat may play out across the central third of the state, roughly from South Texas to the Hill Country and from the Rolling Plains to the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Summer and fall rains were closer to average in these areas, so the landscape is lusher – but the onset of a dry winter will convert that ample grass into handy fuel for wildfire.

The sharp, windy fronts that often punctuate La Niña winters will only exacerbate the threat.

According to the Forest Service’s Texas Seasonal Outlook for winter/spring 2020-21, “Grass production has been above normal in north central Texas and a large portion of south Texas. Both regions are vulnerable to increased dormant season fire activity in grass/brush fuel beds during periods of frontal passage activity.”

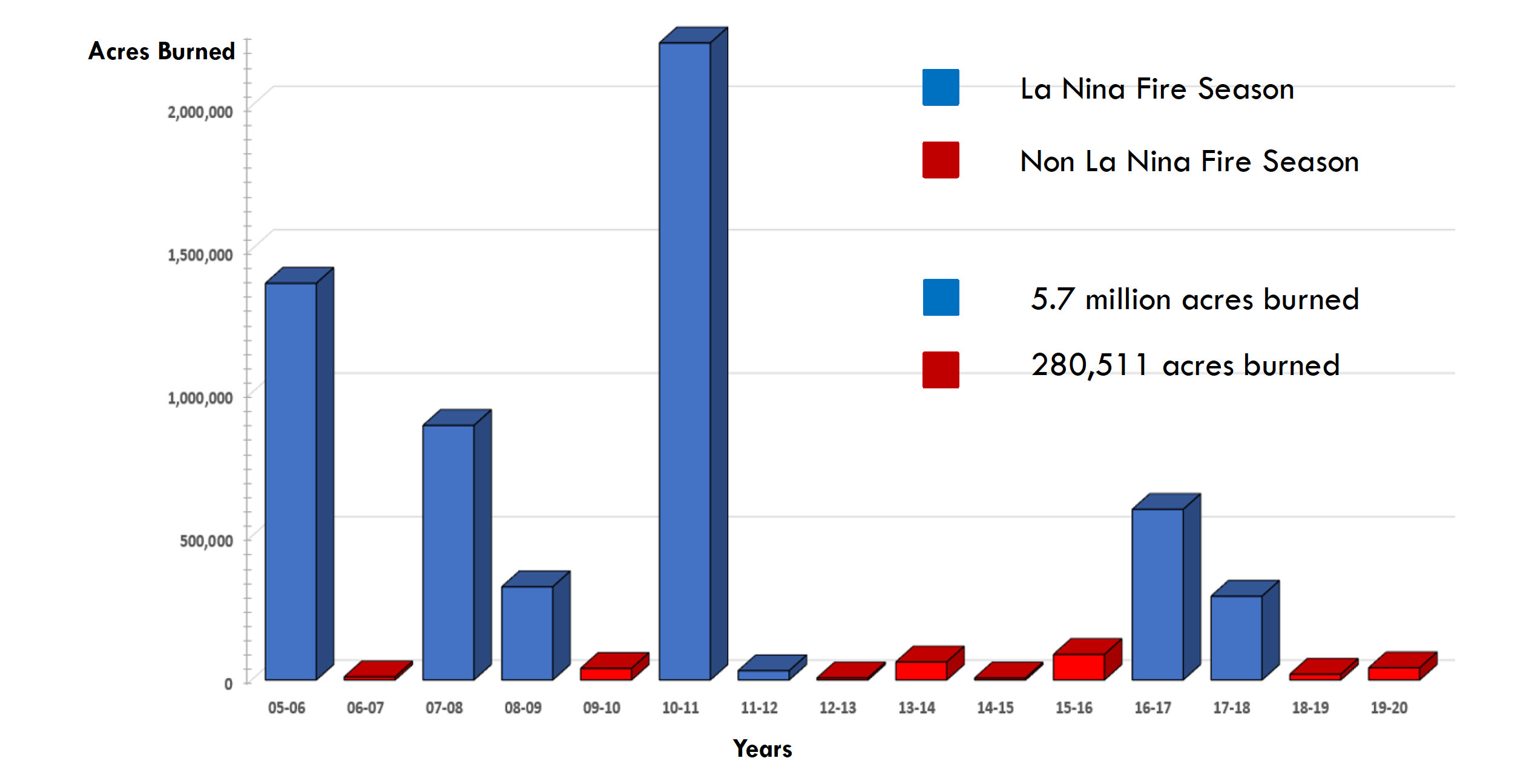

La Niña has been present during fewer than half of Texas fire seasons since 2005, but those La Niña years have led to 95 percent of the total acreage burned. (Source: Texas A&M Predictive Services)

Working toward two-year outlooks, with the help of La Niña

University of Texas climate scientist Yuko Okumura moved to Austin in December 2011, just as a wet winter was starting to dampen that year’s grueling drought. The autumn of 2020 has been the driest Okumura has seen in Austin. “We finally got some rain over the Thanksgiving weekend, but it wasn’t quite enough to thoroughly soak the soil in my flower garden,” Okumura said in an email.

Okumura is part of a small set of atmospheric researchers working on techniques that could push extended climate outlooks from the current one-year time frame toward the two-year range based on the behavior of El Niño and La Niña, which are together known as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

La Niña is defined as a cooling of the uppermost waters in the eastern tropical Pacific, along with a web of atmospheric responses that span much of the globe. El Niño involves a warming of the same ocean region. Both phenomena tend to intensify in the northern summer and fall, peak by winter, and wane by spring.

A crucial difference: El Niño events most often last just one year, whereas about half of La Niña events segue into a second or even third year.

If forecasters can manage to suss out which La Niña events will be long-lived, they may be able to provide more than a year’s advance notice of the likely side effects of a second-year La Niña. Some of these impacts differ from first-year effects. A 2017 study led by Okumura found that drought becomes more likely to spread from the Southwest into the Southeast during the second year of a multiyear La Niña (see NOAA’s climate.gov writeup for more details).

Because La Niña events tend to be closely preceded by El Niño, one forecast clue that’s emerged is the strength of the lead-off El Niño. Three of the most powerful El Niño events on record – those in 1982-83, 1997-98, and 2015-16 – were each followed by multiple years of La Niña, including one or more years of intense Texas drought.

Another clue is the intensity of the first year of La Niña. The stronger it is, the more likely that La Niña will extend to a second year.

For the current La Niña, these two clues are in conflict. It’s already the strongest La Niña event in nearly a decade, and that leads Okumura to believe that it has a chance of extending to 2021-22. However, there was no preceding El Niño in 2019-20, and that suggests La Niña may instead peter out by next summer, according to Pedro DiNezio, a climate scientist who recently moved from UT to the University of Colorado Boulder.

Researchers have been working with a climate model from the National Center of Atmospheric Research that’s particularly adept at handling El Niño and La Niña, in order to assess what controls the duration of ENSO events and to experiment with two-year La Niña outlooks.

Right now, only a handful of climate models successfully capture the difference between the lifespans of El Niño and La Niña, so it will be some time before agencies such as NOAA might issue climate outlooks going beyond a year on a routine basis.

The ultimate payoff could be substantial, though, including longer-range guidance on the odds of a wet or dry winter in Texas and elsewhere. Such advance notice would be valuable for agriculture, utilities, and other interests.

“Given the magnitude of socioeconomic impact, I believe there is significant benefit from long-range ENSO forecasts,” Okumura said. “Early warning of multi-year ENSO events can be used to mitigate the potential climate impact in ENSO-sensitive regions like Texas.”

+++++

Bob Henson is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. A meteorologist and science writer based in Colorado, Henson is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change.”