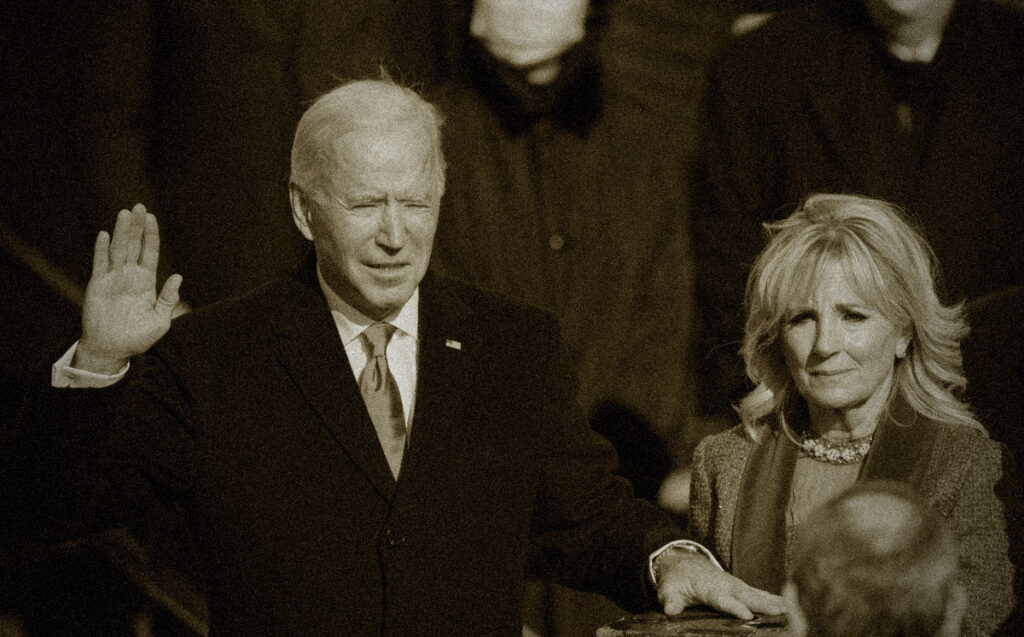

Jan. 20, 2021

U-turn. Sea change. Course reversal. One-eighty. Out with the old, in with the new. Take your pick of descriptions. All of them fit.

With executive orders and appointments, President Joe Biden provided ample evidence in the first hours and days following his inauguration last week that he is enacting a profound shift in U.S. policies related to climate change.

Anyone who paid even a little attention to Biden’s campaign and platform won’t be surprised. Assigning the climate crisis a top priority, he had promised a sweeping and unprecedented set of initiatives to decarbonize the American energy system. The first steps in his assault on climate-disrupting pollution already provide a striking contrast with Donald Trump’s repeated expressions of unconcern about climate change, his mocking of climate science and dozens of rollbacks of regulatory measures.

Beginning shortly after he took the oath of office on Jan. 20, Biden’s actions included:

-

Starting the process for the United States to rejoin the 195-nation Paris Climate Agreement, from which Trump had withdrawn. The 2015 pact was a crucial diplomatic breakthrough to slash heat-trapping pollution from fossil fuels, and the U.S. is the only nation to pull out since then.

-

Canceling Trump administration-issued permission to complete the Keystone XL Pipeline, a long-controversial project to bring especially carbon-heavy (and therefore climate-threatening) Canadian oil to U.S. refineries, including some on the Texas Gulf Coast.

-

Initiating restoration of 2 million acres removed by Trump from a pair of national monuments in Utah. Industries had lobbied the Trump administration to hugely reduce the size of the monuments, which are protected areas akin to national parks, potentially easing the expansion of fossil-fuel drilling and mining there.

-

Declaring a temporary moratorium on oil and gas leasing in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and launching a new analysis of energy development’s environmental impacts in that huge wilderness area. Opponents of drilling there had blocked oil industry efforts to gain access to the Arctic Refuge since the 1970s, but Trump opened it to energy development and rushed out the first drilling leases a day before Biden’s inauguration.

-

Suspending new oil and gas drilling permits and leasing on federal lands and waters for 60 days. The action was viewed as a first step toward fulfilling Biden’s campaign promise of a permanent halt on new drilling and leasing on those publicly owned lands, where the Trump administration had acted to hasten drilling. The suspension also applied to new federal-lands permits for mining of coal, the most potently climate-disrupting of the fossil fuels.

-

Reviewing a number of the Trump administration’s actions and proposing the suspension, revision or rescission of any found to be inconsistent with Biden’s listed environmental and economic principles. The ordered reviews target Trump’s weakened regulations pertaining to heat-trapping methane emissions from oil and gas operations, vehicle emission standards, energy-efficiency standards for appliances and buildings, and toxic air emissions from power plants fueled by coal or oil.

-

Outlining and starting a series of steps to establish rules requiring that federal regulatory actions reflect the “full costs” of climate-disrupting emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Such “costs” are those pollutants’ projected monetary damage to “agricultural productivity, human health, property damage from increased flood risk, and the value of ecosystem services.” The Trump administration had assigned a much lower value to such damages than the Obama administration did, helping to justify weaker regulations.

An Inauguration Day tweet sent a clear message of change.

Declaring intentions, making appointments

The language that Biden used to introduce his beginning attack on climate change was consistent with his campaign and differed dramatically from the then-incoming Trump administration’s framing of its own approach. Soon after Trump’s November 2016 victory, for instance, his first White House chief of staff, Reince Priebus, said the new president largely regarded manmade climate change as “bunk.” Early in the Trump administration, the initial White House budget director, Mick Mulvaney, said Trump didn’t intend to “waste money” on addressing climate change.

In his inaugural address Biden referred to “a climate in crisis” and referred to a “cry for survival [that] comes from the planet itself.” In the preface to his executive orders, he echoed his campaign’s linkage of environmental protection with economic improvement and social justice, declaring that his administration’s policy was:

[T]o listen to the science; to improve public health and protect our environment; to ensure access to clean air and water; to limit exposure to dangerous chemicals and pesticides; to hold polluters accountable, including those who disproportionately harm communities of color and low-income communities; to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; to bolster resilience to the impacts of climate change; to restore and expand our national treasures and monuments; and to prioritize both environmental justice and the creation of the well-paying union jobs necessary to deliver on these goals.

Strong policy language and immediate executive orders are important signals of an incoming administration’s commitment. So are appointments. Before his inauguration, Biden had signaled his intention to follow through on his climate promises with high-level appointments including naming former Obama administration Secretary of State John Kerry, who had helped negotiate the Paris Agreement, as an international climate envoy, and Gina McCarthy, former chief of the Obama EPA, which had developed key emission-cutting regulations, to head a new White House Office of Climate Policy.

Just as telling was the post-inauguration announcement of 20 individuals as the senior leadership team at the Department of Energy to carry out Biden’s “vision for bold action on the climate crisis” under his department chief, former Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm.

E&E News noted that “the team includes two new jobs: a deputy director for energy justice and a director of energy jobs – a nod both to Biden’s pledge to address environmental justice and to his effort to center his climate plan on green energy jobs.”

While Trump had vigorously advanced the production and use of fossil fuels, Biden’s appointment of a new chief of staff for DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy was particularly indicative of the major changes afoot at the department.

She is Shuchi Talati, who had most recently worked as a senior policy adviser at a nonprofit called Carbon180. Its self-described mission is “a world that removes more carbon than it emits.” Talati tweeted that at the Energy Department she would “refocus this office on climate and equity + expand work on carbon removal, industrial decarbonization, carbontech and more.”

Major impacts expected – but not right away

There’s no doubt that Biden’s transformation of climate and energy policies will have major effects – not least in Texas, which is simultaneously a bull’s-eye for various extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change, home of the nation’s oil and gas industry, the leading wind-energy state and a place with huge but largely untapped solar potential. But the results of Biden’s actions won’t be immediate, with their speed and significance depending on a multitude of factors and unpredictable events.

Rejoining the Paris Agreement, for instance, will itself entail a formal diplomatic process and an updated emission-reduction commitment by the U.S. Such voluntary pledges are at the heart of the accord. After rejoining the agreement, the U.S. will also be expected to restore $2 billion of its promised $3 billion for a Green Climate Fund to help developing nations decarbonize their economies.

Consistent with past occasions when stronger regulations loom, some fossil-fuel promoters are already predicting dire harm to those industries from Biden’s actions. But business conditions and trends may mean his highest-profile orders last week are more significant as indicators of his administration’s new path than they are in their near-term economic impacts.

Reuters reported, for example, that major drillers in shale deposits have stockpiled federal-lands permits that can allow them to continue operating there for several years, despite Biden’s promise to halt future permits.

Biden’s Keystone XL action cutting off future shipments of Canadian oil southward is simply “not an issue for refiners” in Texas and Louisiana, because they have increasingly adapted to process different kinds of crude from domestic shale deposits in the U.S. in recent years, an industry analyst told Bloomberg.

And in contrast to their eagerness nearly 50 years ago when oil companies began fighting to gain access to the Arctic Refuge wilderness, interest in drilling there is now “weak” with various economic conditions arrayed against it, National Geographic reported.

The Trump administration remained busy until its last days in actions to roll back regulations and boost fossil energy. After a number of actions to weaken energy-efficiency standards, for example, it finalized a rule just a week before Biden’s inauguration to make it harder for him to boost efficiency standards for some residential furnaces and commercial water heaters.

Even without such last-minute roadblocks, complex procedural requirements for federal rule-making will mean Biden’s efforts to roll back Trump’s dozens of regulatory rollbacks will take varying lengths of time.

From Trump’s first day in office in 2016 until just before the November 2020 election, his administration took 163 actions on about 100 regulations that would “scale back or wholly eliminate federal climate mitigation and adaptation measures,” according to the Columbia University law school’s Climate Deregulation Tracker.

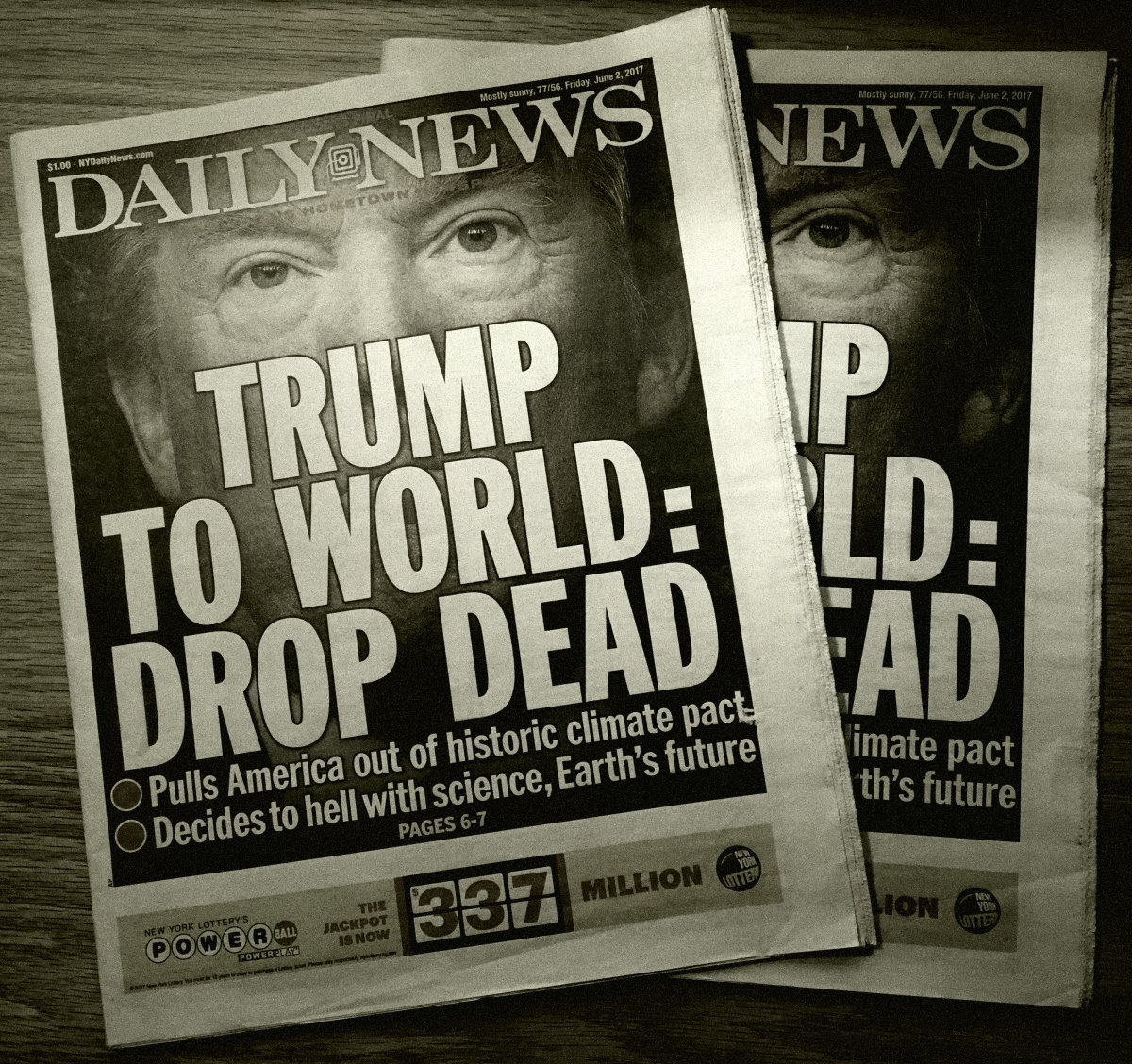

When Donald Trump announced he was withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement five months after he took office in 2017, the New York Daily News reacted with this disapproving headline. It was a distinct echo of the newspaper’s past. In 1975, the Daily News had reported President Gerald Ford’s refusal to approve a federal bailout for nearly bankrupt New York City with an instantly memorable classic of the headline writer’s art: “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”

At that point, about 70 of the regulations were finalized and about 30 were still in process. Some of those 30, such as the rule for furnaces and water heaters, were finalized in the following weeks as Trump attempted to subvert Biden’s victory.

In “Climate Reregulation in a Biden Administration,” a report published last August, analysts at Columbia presented a detailed roster and roadmap for the many actions the new president would have to take to reverse Trump’s deregulatory effort. They wrote:

Reregulating to address climate change is not uniformly an easy task. Where agencies have finalized rules that fail to incorporate or reverse climate mitigation and adaptation goals, for example, the process of reregulating will usually require starting the rulemaking process over. On the other hand, a new administration could revoke President Trump’s executive orders, memoranda, and proclamations, as well certain types of departmental or agency directives and orders, immediately.

After Inauguration Day’s initial set of executive orders on climate and energy, Biden administration officials released a memo indicating more would be forthcoming this week.

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.