The U.S. Secure Fence Act of 2006 led to the construction of different types of barrier along parts of the Texas-Mexico border, including this structure made of 18-foot steel posts (commonly called a “fence”) at The Nature Conservancy’s Southmost Preserve near Brownsville.

Building a fortified wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to stop undocumented immigrants from entering the United States was a central promise of Donald Trump’s successful presidential campaign.

Five days post-inauguration, Trump signed an executive order launching a federal process aimed at planning and constructing a border barrier. In the two weeks since, debate has continued to rage, just as it did during the campaign, over the cost (a new government report says it could be as high as $21.6 billion for “a series of fences and walls”), whether Mexico will pay for the project (as Trump promised and Mexico vows it won’t do), and whether a wall (or “fences and walls”) would actually stem unauthorized immigration.

Another issue is less prominent but has particular importance in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas and adjoining areas of Mexico: How might Trump’s wall affect wildlife of that binational region, one especially rich in biological diversity and a focus of extensive wildlife-conservation efforts for decades?

Melissa Gaskill, an Austin-based journalist who holds a degree in zoology and specializes in writing about wildlife and other nature- and science-related subjects, examined that question for Texas Climate News.

+++

By Melissa Gaskill

A presidential executive order signed on Jan. 25, titled “Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements,” states in part: “It is the policy of the executive branch to…secure the southern border of the United States through the immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border….”

The order directs the secretary of the Interior to “take all appropriate steps to immediately plan, design, and construct a physical wall,” defining “wall” as a “contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and impassable physical barrier.”

Meant to be impassable to humans, the structure also will stop most wildlife.

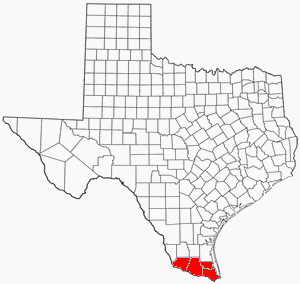

The official U.S.-Mexico border bears little relation to the natural world. Arizona’s Sonoran Desert and Sky Island ecosystems, for example, extend well south of the border into northern Mexico. Currently, barriers of different kinds that were mandated by the Secure Fence Act of 2006 extend intermittently along 650 miles of the border from California to Texas. In 2011, scientists from the University of Texas and Yale University identified three regions where walls would most harm wildlife, including coastal California, Arizona’s Madrean Sky Island Archipelago, and the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas.

One species particularly at risk in the Valley is the ocelot, a small, spotted wild cat. The 55 documented in the U.S. include a breeding population in the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge.

Male ocelots need about 25 square miles of territory, females around nine square miles. The refuge covers 90,000 acres scattered among 115 separate units in this highly developed area, a habitat further fragmented by existing border fence. The fence also separates the cats from a larger population in northern Mexico. Scientists consider interbreeding between these two populations critical to maintaining genetic diversity and, ultimately, survival.

“If we cut off wildlife populations that are typically migratory or cover large distances, it results in decreased exchange of genetic material, or inbreeding,” says Bryan Bird, southwest program director for the national conservation organization Defenders of Wildlife. “Biologists call it a genetic bottleneck, which can lead to extinction.”

Bird points out that a breeding population of mountain lions in the area of Big Bend National Park, adjacent to the Rio Grande in the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas, also crosses back and forth across the border.

In the Valley, the existing border barrier doesn’t even follow the actual border – a winding, flood-prone river – but runs several miles north of it in places, continuing in straight lines when the river turns. That leaves a lot of U.S. land on the Mexican side of the barrier, including more than 85 percent of the private Nature Conservancy’s Southmost Preserve near Brownsville; all of the nearby Sabal Palm Sanctuary; parts of several state Wildlife Management Areas; and significant portions of three national wildlife refuges – Lower Rio Grande Valley, Laguna Atascosa and Santa Ana. This makes managing wildlife on these properties difficult and hampers cooperation between the two countries.

+++

“We are losing lands at a faster clip than any other state, and nowhere is that more true than in this part of Texas. Anything that further fragments [wildlife habitat] is a serious concern, and fences are a type of fragmentation.”

+++

A 2008 report from Lindsay Eriksson and Melinda Taylor with the University of Texas School of Law stated: “The direct effects of border wall construction and maintenance will be significant and detrimental to past, present, and future conservation efforts.”

In some areas, the existing barrier prevents animals from reaching the river for water. Sections constructed of solid concrete to retain floodwaters could trap and drown wildlife in those waters. Wide areas cleared of brush on either side of existing barrier and high-intensity lighting also can affect the movement and behavior of wildlife.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages national wildlife refuges and enforces the Endangered Species Act among other duties, declined to comment on the executive order’s potential effect on wildlife when it issued this statement on January 27:

“Any assessment of the potential impacts of a U.S.-Mexico border wall on threatened and endangered wildlife would be made through the formal consultation process under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, once initiated by the federal action agency involved. We have not received a request for such a consultation from any agency and would not make speculative assessments outside of that process.”

The Valley is one of the most biodiverse places in North America, with more than 700 species of vertebrates and, thanks to its location at the convergence of two major flyways for migratory birds, some 500 bird species. Communities, organizations and agencies here spent more than a decade building a robust nature-tourism industry, which brings $463 million to the area each year, according to the nonprofit Rio Grande Valley Nature Coalition.

The process of building the first wall segments definitely hurt terrestrial wildlife in the region, says Ken Merritt, former project director at the South Texas Refuge Complex, which includes 180,000 acres in three national wildlife refuges in the Valley. “Not much thought was given to it, fence was put in just kind of willy-nilly. But it was in segments, so wildlife still had a chance. If a continuous wall goes in, that will definitely have a lot of effects on wildlife that we haven’t seen yet.”

A study by Texas A&M University in 2014 reported that Texas has one of the highest rates of habitat fragmentation in the country. Fragmentation – breaking the landscape into smaller and smaller undeveloped pieces – reduces overall availability of space for wildlife and makes it more difficult for those animals to find food, shelter and mates.

“We are losing lands at a faster clip than any other state, and nowhere is that more true than in this part of Texas,” said Laura Huffman, director of The Nature Conservancy in Texas. “Anything that further fragments is a serious concern, and fences are a type of fragmentation.”

While the executive order calls for “comprehensive study” of border security, geophysical and topographical aspects and available resources, it fails to mention how additional physical structures could affect wildlife, the natural environment, and people and communities economically dependent upon them.

“The international border is not just a shared human community, it is a shared ecological community with shared wildlife,” Bird sums up. “It is one ecosystem on both sides along the entire 2,000 miles of border.”

+++++

Melissa Gaskill is an Austin-based writer whose work has been published by Nature News, Scientific American, Wildflower, Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine, Smithsonian, Men’s Journal and others. She received a bachelor’s degree in zoology from Texas A&M University and a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin.