The Texas high-speed rail line will use the Japanese Series N700 bullet train.

By Kelly Calagna

Texas Climate News

Texas, the nation’s top producer of CO2 emissions for decades, could become the location of the United States’ first carbon-reducing high-speed rail system to connect the state’s two most populous urban areas.

Planning for the $15-billion Houston-Dallas bullet train has been underway for several years, drawing strong opposition along its route. But now Texas Central, the company behind the project, says construction could begin late this year or early next year on the system it says would offer millions of Texans an efficient way to get between cities, reducing both travel time and emissions.

The high-speed train will be capable of traveling at speeds up to 205 mph, making the current four-hour drive between Houston and Dallas whiz by in a mere 90 minutes, stopping only once along the 240-mile journey in a station planned between College Station and Huntsville.

The train selected for the project is Japan’s Series 700Ni bullet train, or “Shinkansen” in Japanese. The model is a variation of the train used on Central Japan Railway’s (JR Central’s) Tokaido Shinkansen line for express service between Tokyo and Osaka.

The Japanese train is electric and uses a regenerative breaking technology that captures and reuses kinetic energy to slow the vehicle. Its carbon footprint is less than 10 percent of the emissions produced by a commercial jet making the same journey, while carrying up to seven times as many passengers, according to JR Central. The Tokaido Shinkansen line, the busiest high-speed rail (HSR) service in the world, has been successfully running for over 50 years and currently serves more than 450,000 travelers per day, significantly reducing travel-based greenhouse-gas emissions in the region.

Japan debuted the world’s first bullet train in 1964 – just in time for the Summer Olympics in Tokyo – and has since grown its Shinkansen network to connect 22 of its major cities. The success of the country’s HSR as a desirable, low-impact and profitable form of travel prompted other nations to invest in the technology, bringing HSR to Europe and other parts of Asia. Around the world there are over 45,000 kilometers of operational HSR lines. None are located in the United States.

The U.S. alone produces 15 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels – a dominant share second only to China’s. Transportation accounts for 36 percent of those emissions, the majority of which are attributed to passenger cars and light-duty trucks such as SUVs, pickup trucks and minivans, according to an annual report by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. However, as a sprawling nation with widely dispersed urban centers, the country has been unable to effectively make the transition from roads to rails.

The U.S. has made efforts to create HSR systems for decades, but plans have either fallen short or fallen through. In the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak’s Acela Express reaches a top speed of 150 mph, but only for portions of the route; overall it averages about 66 mph. In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom recently announced that the proposed HSR project to connect Los Angeles to San Francisco would be significantly scaled back. The reasons, he stated in his Feb. 12 State of the State Address, were that “the project, as currently planned, would cost too much and take too long.”

Newsom’s words echoed similar reasons for the collapse of the proposed Texas TGV bullet train in the early ’90s, which was intended for the same corridor as the new Texas Central project. Texas TGV faced concerns about financing, profitability, eminent domain, noise and especially the impact on rural communities. After a tumultuous series of public meetings, the project failed to meet a financial deadline and disbanded in early 1994.

Similar hurdles face the new HSR project in Texas. Rural residents and opposition groups are contesting Texas Central’s right to acquire land through eminent domain in an ongoing battle in the courts. There has also been a persistent effort by staunch opponents to block or hamper the project in the Legislature, though past attempts have been largely unsuccessful. But despite these potential obstacles, timing may be in Texas Central’s favor.

Earlier this year, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a New York Democrat, and Democratic Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts proposed the Green New Deal. The multifaceted proposal includes the development of high-speed rail systems as part of the ambitious 10-year national mobilization plan to “[overhaul] transportation systems in the United States to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector […].” The Green New Deal, drawing criticism from Republicans and even some Democrats, failed to gain traction in Congress last month, though it has fared well in some polls and has been credited with energizing the national debate over climate policy.

Assessing emissions

The rail industry says HSR is the cleanest means of motorized transportation available. After evaluating the upfront emissions of planning, construction and operation, bullet-train systems can be up to 14 times less carbon intensive than travel by car and up to 15 times less than flying by plane, according to the International Union of Railways (UIC). However, an HSR project’s carbon footprint is directly related to how much traffic it diverts from the sky and road to the rail.

A ridership study commissioned by Texas Central projects ridership of the Houston-Dallas line to be 5 million riders annually once the line is complete in the mid-2020s. The study found that about 14 million journeys are made between Greater Houston and North Texas each year, 90 percent of which are by road. To encourage travelers to ride the rail, Texas Central has prioritized the line’s time-efficiency and relative cost, which the company said should be similar to the cost of driving for a basic ticket, or comparable to airfare for a more comprehensive experience.

The drive time between the areas is projected to significantly increase as Texas’ urban population continues to rise. Vehicular traffic along Interstate 45 between Houston and Dallas is expected to rise 200 percent by 2035, according to the Federal Railroad Administration’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the railroad.

The impact statement said the HSR would remove up to 14,630 vehicles per day along the busy corridor, saving 81.5 million gallons of gasoline per year, or an estimated 724,291 metric tons of CO2. This would generate energy savings that would offset the rail project’s construction and operation to become a net benefit by reducing energy consumption.

The power for the electric train will come directly from the Texas grid. “The good news is that the Texas grid is becoming increasingly [greener] as solar and wind technologies advance,” said a representative for Texas Central. “As the Texas grid gets greener, so will the train.”

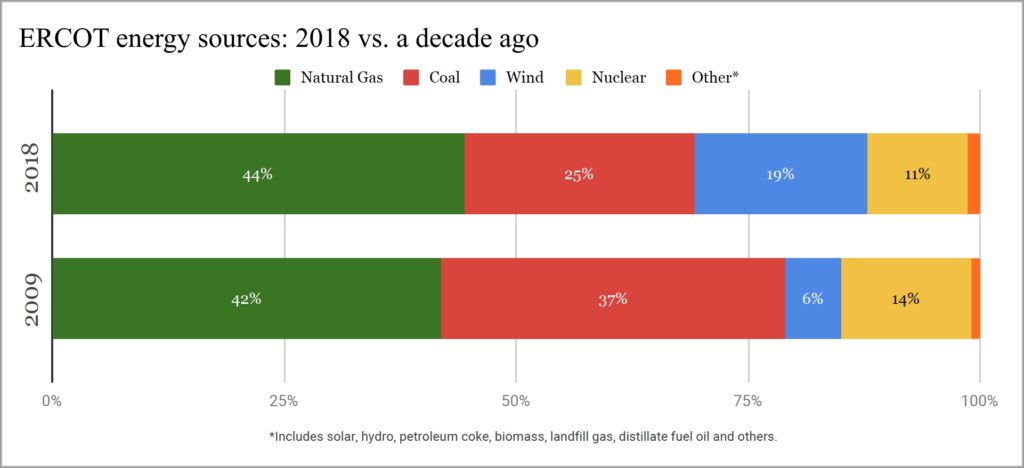

While Texas is by far the nation’s top producer of CO2 from fossil fuels – 13.5 percent, which is almost as much as the next three states combined – it is also the nation’s top producer of wind energy. From 2009-18, wind-generated electricity tripled to 19 percent of all power production in the area covered by ERCOT, the grid-management agency for most of Texas.

Coal, the biggest emitter of climate-warming CO2 among the major electricity sources in the ERCOT region of Texas, has declined while wind power has increased.

With growing discussion about the Green New Deal and other major efforts to combat climate change, such as an economy-wide carbon tax, plus increasing pressures pushing for sustainable development in general, the time may finally be right for the United States to embrace HSR. For now, Texas is on track to be the place where that transition begins in a major way.

+++++

Kelly Calagna is a contributing editor for Texas Climate News. She is an independent journalist based in Houston, covering topics related to climate, science and the environment.

Image credits: Photo – Central Japan Railway via Texas Central. Chart – Kelly Calagna, based on data assembled by Joshua Rhodes, University of Texas Energy Institute.

![]()

![]()