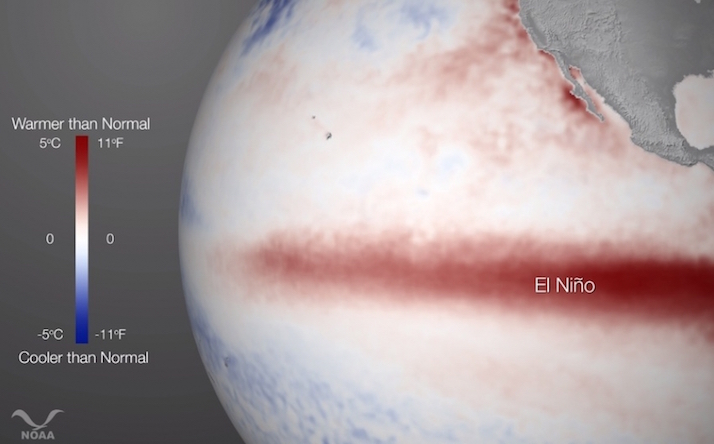

Sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean during the very strong 1997 El Niño event

By Andrea Thompson

Climate Central

The El Niño event underway in the Pacific Ocean is impacting temperature and weather patterns around the world. But its effects aren’t confined to the atmosphere: A new study has found that the cyclical climate phenomenon can ratchet up sea levels off the West Coast by almost 8 inches over just a few seasons.

The findings have important implications in terms of planning for sea level rise, as ever-growing coastal communities might have to plan for even higher ocean levels in a warmer future. In California alone, some $40 billion of property and nearly 500,000 people could be affected by the sea level rise expected through mid-century, not including any additional boost from El Niño events.

“This paper is an important reminder that we cannot neglect interannual sea level variability and we need a quantitative understanding of its impact,” John Church, an oceanographer with Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) said in an email.

‘Best of both worlds’

El Niño is a Pacific-driven climate pattern that features warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropics of that ocean basin. (That excess heat can bleed into the atmosphere and cause changes to typical circulation patterns.)

When water warms, it expands; in the case of the oceans, that means higher sea levels. This is part of what is causing the global-warming linked long-term rise in the oceans, as they absorb much of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. (Melting land-bound glaciers are also contributing to overall sea level rise.)

But while it’s clear that the sea surface rises in the main El Niño regions of the tropics, the effects further afield and on smaller scales have been harder to tease out, particularly along coastlines.

Oceanographer Benjamin Hamlington set out to see if he could find an El Niño sea level rise signal around U.S. coasts, by putting together data from tide gauges and satellite altimeters, which measure sea surface heights. While tide gauges have longer records, they are sparsely situated along coasts, while satellites can get a more detailed and widespread view of ocean levels.

It’s a way to get “the best of both words,” Hamlington, an assistant professor at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va., said.

El Niño’s Effects

The clearest signals from El Niño on coastal sea levels were found along the West Coast; the find wasn’t surprising given that El Niño is a Pacific-based phenomenon.

On Hamlington’s charts, for example, the very strong El Niño events of 1982-83 and 1997-98 clearly jump out in the West Coast data. While the tide gauge and satellite data largely agreed, the satellites seemed to slightly underestimate the El Niño-related rise.

Unsurprisingly the biggest seasonal effects on sea level came during the fall and winter months, when El Niño events typically reach their peak.

La Niña events — the counterpart to El Niños, featuring colder than normal tropical Pacific waters — caused dips in sea levels. None were as large as the El Niño shifts, but there were no exceptionally strong La Niñas in the record Hamlington used.

There also seemed to be some El Niño effect on sea levels off the Southeast coast, which Hamlington said could be due to increased storminess and related storm surge.

Planning Ahead

While previous studies had examined the effects of El Niño on sea levels, namely around Australia, this one was the first to look at the U.S. and combine tide gauge and satellite data. The new study has been accepted to the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans.

Understanding how such year-to-year natural climate variations impact coastal water levels is key to developing a full picture of the sea level rise threat through the end of the century. Warming alone is expected to cause up to two feet of rise along the West Coast, according to the National Climate Assessment.

Those planning how to protect their communities from sea level rise need to know the full range they could face, Hamlington and Church, who was not involved with the study, said. A strong El Niño in the future could mean that cities face even higher sea levels than the largest projections from warming.

“The impacts of sea level change will be felt most acutely during periods of high sea level, both from this type of interannual (and decadal) variability as well as extreme events,” Church said.

This study, he added, is a good step toward piecing all those bits of information together to get a fuller picture of what future sea level rise holds in store.

+++++

This article was originally published by Princeton, N.J.-based Climate Central, an independent organization of scientists and journalists researching and reporting on the science and impacts of climate change.