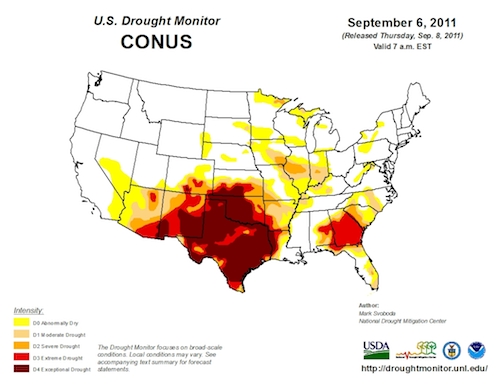

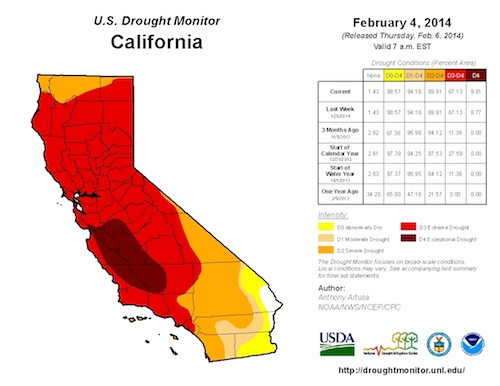

The bright red that signifies “extreme drought” and, even worse, the deep maroon that means “exceptional drought” now cover most of the map of California. Just as they covered most of the Texas map in mid-2011.

News accounts from California over the last couple of weeks described looming water shortages, officials scrambling to deal with the unfolding crisis, attendant political friction, imminent damage to the state’s vital agricultural sector and mounting harm to its wildlife resources.

In general and aggregate terms, it sounds a lot like the situation in Texas, three years back.

You might (unscientifically) call it a tale of two droughts. Or, if some scientists are right, the hyper-dry conditions in California this year, along with the hyper-dry conditions in Texas in 2011 (conditions that linger, though thankfully not nearly in such a “hyper” way) may turn out to be part of a single decades-long “megadrought.”

State climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon has warned his fellow Texans numerous times that the state’s continuing dry spell could drag on for several more years and may statistically eclipse the state’s “drought of record,” a multi-year, low-precipitation period in the 1950s.

That state-specific scenario, however, is not the same thing as the multi-state “megadrought” that some other climate experts have been mulling as a possible explanation for a much longer dry spell that has been gripping much of the Western U.S.

Such long-lasting droughts have affected the region – indeed, on occasion the entire continental United States – in the past, the news-and-science organization Climate Central reported, describing a December presentation at a large annual conference of the American Geophysical Union:

“The current drought could be classified as a megadrought — 13 years running,” paleoclimatologist Edward Cook, director of the Tree Ring Laboratory at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., said at an AGU presentation…. “There’s no indication it’ll be getting any better in the near term.”

But the long period of drought the West is currently experiencing may not be a product of human-caused climate change, and could be natural, he said.

“It’s tempting to blame radiative forcing of climate as the cause of megadrought,” Cook said. “That would be premature. Why? There’s a lot of variability in the system that still can’t be separated cleanly from CO2 forcing on climate. Natural variability still has a tremendous impact on the climate system.”

In the past, Climate Central added, “long-lasting drought events have been tied to fluctuations in ocean conditions, which can alter large-scale weather patterns.”

Casting this month’s water restrictions and appeals for conservation in California in a regional context, a U.K.-based climate news organization quoted a researcher who sees the situation as part of a changing climate:

A vast area of land in the western region of the American land mass, stretching from the province of Alberta in Canada across to parts of Texas in the U.S. and on down into Mexico, is suffering as reservoirs and rivers dry up. A state of emergency has been declared in several areas, including California.

Wallace Covington is director of the Ecological Restoration Institute at Northern Arizona University. “What we’re seeing across this region is an intensification of long-established aspects of climate change”, Covington told Climate News Network.

“I hate to sound pessimistic but all around in these large watersheds we’re seeing a degradation of water structure and function. There’s increased erosion leading to desertification, and with the dry conditions and generally stronger winds the forest fire season is being extended.”

CBS News, meanwhile, quoted the general manager of a Nevada water agency that manages the shrinking Lake Mead, which supplies water to 20 million people in southern California, Nevada and Arizona, about his troubles with a changing climate:

“It’s a pretty critical point. The rate at which our weather patterns are changing is so dramatic that our ability to adapt to it is really crippled.”

California’s growing predicament was dramatized on Jan. 31 when state officials announced that for the first time in its 54-year history, no water would be released from a huge system of reservoirs to local agencies.

The Associated Press noted that this action “does not mean that every farm field will turn to dust and every city tap will run dry,” because the 29 cut-off agencies have other water sources, “although those also have been hard-hit by the drought.”

Despite welcome rains a few days ago, the AP reported that a National Weather Service hydrologist said they had not made “a significant dent” in the water-supply crisis.

That appraisal was echoed on Tuesday by the San Jose Mercury News: “Despite last week’s showers, the lack of rain in California this winter is having a dire impact on the rivers and reservoirs that power the state’s hydroelectricity plants.”

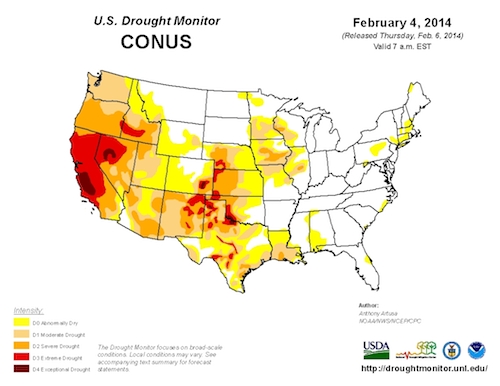

While both states are affected by drought, the current situations in Texas and California have major differences.

About 67 percent of California was in the “extreme” or “exceptional” drought categories – the two most critical – in the U.S. Drought Monitor’s weekly report last Thursday. None of the state was in those categories a year ago.

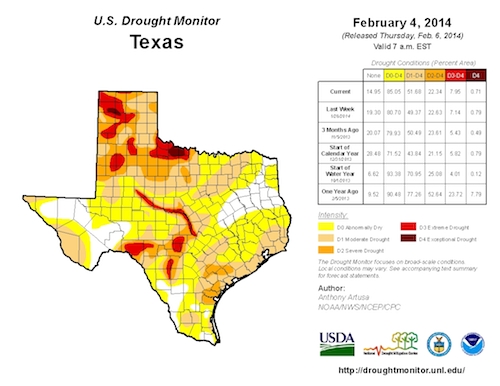

In Texas, by contrast, only about 8 percent was affected by “extreme” or “exceptional” drought in last Thursday’s report – a big drop from the 24 percent a year before.

Still, most of the area of both states was classified last week as “abnormally dry” or in one of four “drought” categories – 99 percent of California (up 1 percent since the start of the year) and 85 percent of Texas (up about 14 percent in the same period).

And news accounts from the past few weeks have illustrated that, drier though California is at the moment, both states are grappling with many similar concerns.

As in Texas, in 2011 and since then, agricultural impacts have been prominent in news from California, a legendary food producer.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported:

California’s great Central Valley aquifer and the rivers that feed it, already losing water in the changing climate, are now being drained because of the drought, leaving water levels at their lowest in nearly a decade.

Water experts say many farmers who depend on the huge water source beneath the valley for irrigation will have to resort to pumping water from ever deeper levels at greater costs, even as they plant crops on fewer and fewer acres as more of their land is gobbled up for development.

“The combination of climate change, growth and groundwater depletion spells a train wreck,” said James Famiglietti, a water resource expert and director of the UC Center for Hydrologic Modeling at [the University of California]-Irvine.

The Bloomberg news service reported that California’s water emergency, after its driest year on record, “is likely to boost the prices of everything from broccoli to cauliflower nationwide. Farmers and truckers stand to lose billions in revenue, weakening an already fragile recovery in the nation’s most-populous state.”

In an article focused on the farm situation, the AP reported “the nation’s leading agricultural region is locked in drought and bracing for unemployment to soar, sending farm workers to food lines in a place famous for its abundance.”

In Texas, meanwhile, agricultural impacts and their reverberations continue to be felt.

Lubbock’s KJTV reported that hundreds of employees are still out of work a year after Cargill’s Plainview beef-processing plant closed because of “ongoing drought and a dwindling cattle supply.” Waco’s KWTX, meanwhile, reported that the National Agricultural Statistics Service had declared the nation’s January cattle inventory was the lowest since 1951 with a 4 percent decrease in Texas, the leading cattle-producing state.

In farming-related news with much broader ramifications, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality commissioners on Wednesday delayed a decision on an agency staff recommendation that they approve another emergency plan for the Colorado River that would likely mean the Lower Colorado River Authority would later cut off water to downstream rice farmers, who need it for irrigation, for the third straight year.

The hotly contentious proposal, debated during hours of testimony before the environmental commissioners, was supported by upstream users of Colorado River water (such as Austin) and opposed by farmers downstream along with environmentalists who contend that it would go too far in depriving seafood and other wildlife species in Matagorda Bay of sufficient inflows from the river.

(The mathematically complex TCEQ proposal and the competing water demands it addresses were detailed in a Texas Tribune article on the commissioners’ deferral of a decision on the issue until after an administrative law judge issues a recommendation.)

The long-running argument over how to apportion Colorado River water among urban, industrial, agricultural and wildlife demands – at a time when reservoir lakes in Central Texas are only a little above a third full – has echoes in California.

In that state, with a considerable more severe drought than Texas’ at the moment, competition for dwindling water resources – and the political jockeying that goes along with it – have begun to intensify.

The McClatchy news service reported that one unfolding tussle over water set aside by farmers last year for later use “underscores the tricky balancing act that California’s drought now forces on farmers, water managers and lawmakers alike. As reservoir levels drop, myriad competing tradeoffs are coming to light. The longer the drought lasts, the harder these choices become.

And just as downstream wildlife resources in Texas have been spotlighted by environmentalists in the debate over how to divvy up Colorado River water, drought-impacted wildlife species in California have been drawing attention as the drought there grew more intense in January and the first part of this month.

California prohibited fishing in some streams late last month, trying to safeguard salmon and steelhead trout that depend on those waters for crucial life-cycle development.

The Los Angeles Times reported this week that drought conditions were blocking migratory paths along some streams for coho salmon, with the situation especially crucial along California’s northern and central coasts, where a population of a few thousand of the fish was “already teetering on the brink of extinction.”

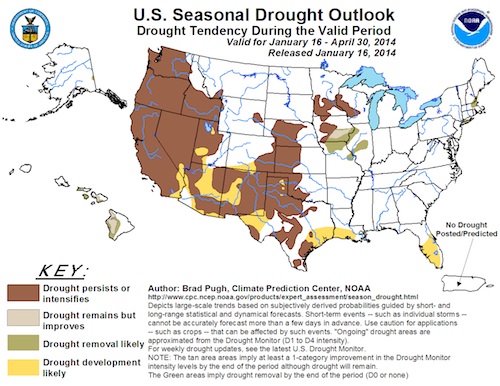

The most recent Drought Outlook from federal scientists projects drought conditions will likely persist, intensify or develop throughout California and across about half of Texas.

– Bill Dawson

Image credits: U.S. Drought Monitor, National Weather Service