By Bill Dawson

Besides their dramatic, immediate impacts – the harm to people and property and nature – environmental disasters can exert a profound influence on attitudes and actions, including the policies that governments and businesses adopt.

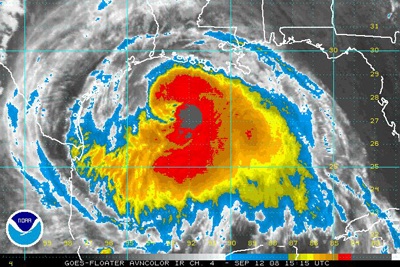

Hurricane Ike, NOAA GOES 9/12/2008 10:15 CDT

Think of the toxic waste at Love Canal in New York State. The nuclear plant accident at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. The runaway chemical reaction that killed thousands at Bhopal, India. The mammoth oil spill from the Exxon Valdez in Alaska. Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of New Orleans and coastal Mississippi. All prompted far-reaching study, debate and policy changes.

With that history of catastrophe-catalyzed response, it’s reasonable to wonder whether Hurricane Ike, which roared across the upper Texas coast in September and ranks unofficially as one of the costliest hurricanes in U.S. history, will combine with the memory of other recent storms in Texas and Louisiana to help propel Texans toward new ways of thinking and behaving with regard to climate change and sustainability.

After all, the world’s leading scientific body assessing manmade global warming, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), declared last year that it is “likely” hurricanes will become more intense and “very likely” that extreme weather events, including heavy precipitation, will be more frequent.

In addition, scientists expect hurricanes’ storm surges to become more destructive because of sea level rise, which the IPCC said is projected to increase as a result of human-caused warming. Ike’s storm surge caused extensive flooding in Galveston and catastrophic damage along the Bolivar Peninsula to the north.

An Ike-energized Texas conversation about climate change and related sustainability issues could encompass a wide variety of topics, related both to mitigating the effects of manmade warming and to planning for, and adapting to, its projected effects.

A few examples:

- Should Texans adopt more policies and practices to reduce the state’s considerable production of carbon dioxide, the principal greenhouse gas that scientists say is warming the atmosphere? Texas ranks No. 1 among the states for CO2 emissions.

- Is it wise to encourage or even permit building (or rebuilding, as the case may be) in some hazard-prone locations near the coast? Thousands of homes were flooded by Ike. Related questions involve the extent to which all Texans should share the financial risk of coastal residents through the Texas Windstorm Insurance Pool.

- Should Texas require utility companies to take protective measures for their electricity-distribution systems, as Florida did, to “harden” them against hurricane damage? State regulators considered doing this after Hurricane Rita in 2005, and the question was revived when Ike cut off power to millions of people, some for weeks.

There are other signs of increased public discussion of climate and related sustainability issues.

“Should we rebuild Galveston?” Houston Chronicle science reporter Eric Berger asked readers of his blog on Sept. 23. “The question we must ask ourselves…is whether it’s prudent to rebuild and continue the development of unprotected areas along the Texas coast such as Galveston’s west end and Bolivar Peninsula.”

And in an op-ed column in the Chronicle on Nov. 5, representatives of Houston-area conservation organizations called for a variety of actions “to achieve ‘community resilience’ to coastal hazards” in response to Ike. Their recommended actions included preventing construction in floodways, expanding greenways beside area bayous, reforestation to boost rainwater retention and air quality, and encouraging “hardening” of the electric system.

Whether or not Ike and other recent storms may prompt more sustainability-oriented actions is complicated, to put it mildly, by the worsening problems that have gripped the U.S. economy in recent weeks.

Texas has become the national leader, for instance, in generating CO2-free wind energy. But state and national news outlets have recently reported that credit problems could slow the growth of alternative energy ventures.

In the public sector, Texas has not launched most of the types of initiatives to address climate change that have been undertaken by other state governments, though some Texas officials have been discussing options for more action in this area.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of Texas cities have been adopting policies to reduce greenhouse emissions from municipal operations. But at both the state and local levels, the current economic downturn at least clouds the outlook for such initiatives, even if a string of destructive storms were to make their adoption more appealing.

To explore where Texas may be heading in terms of attitudes and actions regarding climate change and sustainability, Texas Climate News interviewed several individuals with varying perspectives – an historian, a sociologist, an economist, a municipal official and an environmental group leader.

Historian’s Viewpoint

Michael Melosi

Ideally, a dramatic event like Hurricane Ike would open up a public discourse over the broad question of sustainability, along with its various sub-issues, said Martin Melosi, a history professor at the University of Houston who specializes in environmental, urban and energy history and is director of the Institute for Public History at UH.

“In some respects, can Ike, Allison, Gustav, Katrina and Rita be harbingers of things to come? Can they also be a wake-up call?” he said, referring to major storms that have battered Texas and Louisiana since Tropical Storm Allison inundated large areas of Houston in 2001.

Melosi confessed that he is not very optimistic that these disastrous storms will prompt Texans to rethink and change longstanding patterns of living.

“Sustainability is a really problematic term – one problem is it covers a wide waterfront of possible responses. In some ways it’s a very conservative idea, but on the other hand it’s a lifestyle-changing concept,” he said.

“Conserving resources, designing systems that will have long-term benefits, not just short-term economic gain – these are some things that don’t set well with Americans in many cases.”

Considering Houston – and especially Galveston – after Ike, “can we foresee it producing any systems, any structures, any changes at all that reflect a sustainable approach?” he said. “To me, the difficulty is always the difficulty of having too many stakeholders, with private property rights coming directly into a clash with regulation of some kind.”

The issue of coordination, especially evident in post-Katrina New Orleans, complicates matters further, he said.

“Who is the one who will bring together the parties and say, OK, let’s plan for the future in a sustainable way? Will it be government? And if it is government, will it be the state government, local or federal government? Utility districts? Special districts? How do you coordinate activities to create a society that might require more planning – and long-term planning – to accomplish those kinds of goals?”

The “least cynical” answer to such questions is that some people and groups will view the crisis following hurricane devastation as an opportunity to bring about change, he said.

“Other people will want to get back to a lifestyle that they had before. I guess we’ll see some of this in terms of what happens on (Galveston’s) West Beach and Bolivar – the cases where already the dialogue is hitting the extremes. One side is saying don’t redevelop, we’re just going to see this happen again, why should the taxpayers pay for the folly of individual property owners? Why should we pay for roads and utilities and so forth for people who are putting themselves in jeopardy? The other side is saying these are our homes, these are our summer places, we don’t want to lose that. We want to return to the way things were and hope that the next time it hits Louisiana and not us.”

Compounding the issue of coastal development is the reality of an eroding shoreline, Melosi said. “I hope we would take a hard look at what the environmental realities are and what you can actually sustain there, even if there was not another hurricane.”

Growing economic problems, however, will only complicate any efforts to address long-range issues that Ike has highlighted, he said.

“Political leaders now are trying to figure out how do we recover from these current disasters with the preoccupation we have to have with the current financial crisis, which does dovetail into our post-Ike problems,” he said.

“The bond markets, interest rates, federal government subsidies and support – which seemingly does not relate to our current woes, in the long run does relate,” he said. “To what degree long-term issues are addressed in the midst of all this activity is hard to predict. It’s hard to criticize political leaders who are having to deal with on-the-ground, immediate problems.”

Houstonians’ attitudes and Houston’s future

Stephen Klineberg

“No one knows, of course, how deep and how long the current recession will be, but it’s surely clear that short-term economic needs will take precedence over longer-term investments,” agreed Stephen Klineberg, a sociology professor at Rice University and director of the Houston Area Survey, which has tracked residents’ attitudes about major public concerns since 1982.

“On the other hand,” he said, “some part of those short-term investments – putting people to work at jobs that cannot be outsourced – might well find expression in rebuilding the urban infrastructure and in subsidies to support investments in conservation energy in homes and transportation systems.”

In Texas, much will depend on directions set by the new administration in Washington, Klineberg said.

“Meanwhile, the longer-term challenge will continue, as Houston and Texas gradually come to recognize the need to address the quality-of-life issues that will affect this city’s and state’s ability to attract the talent and resources that will grow their economies in the 21st century.”

The 2007 Houston Area Survey included several questions that relate to climate change specifically and sustainability more broadly.

Some examples:

- “Requiring power plants to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases, even if electricity rates rise.” Agree – 65.7 percent. Disagree – 24.8 percent.

- “Raising taxes to set aside and protect wetlands, forests and prairies throughout the Houston area.” Agree – 60.6 percent. Disagree – 34.3 percent.

- “Strengthening pollution controls will result in too many restrictions on individuals and businesses.” Agree – 34.9 percent. Disagree – 57.0 percent.

- “Need better land-use planning to guide growth or leave people free to build wherever they want?” Better planning – 69.8 percent. Free to build – 22.4 percent.

- “Would you favor or oppose creating a General Plan to guide Houston’s future growth?” Favor – 82.8 percent. Oppose – 10.5 percent.

“There’s a clear consensus among Harris County residents that we’ve got to plan this city, that there’s going to be another one million people moving here in the next 20 years,” Klineberg said.

He believes Ike will be another factor helping to firm up public opinion on the subject of climate change.

“Ike is just one more piece,” he said. “No one episode can be attributed to global warming. Ike in itself wouldn’t have done very much. But in conjunction with everything else, it’s a further consolidation of a paradigm shift that has occurred in the minds of the general public.”

Events like Ike “concentrate the mind,” he said, “but the great challenge of global warming is that we have to respond before the evidence is overwhelming. The real lesson about the challenge of global warming is that we have to respond in advance.”

Texas is at the center of the climate change issue, because it will be affected both by efforts to limit warming and by its projected consequences, Klineberg said.

Whatever new energy policies emerge under the new federal administration will include more emphasis on alternative energy sources and mandatory improvements in energy efficiency, he said.

“Houston needs to figure out a way to recover more quickly – to build electric systems and high-rise buildings more intelligently to withstand and recover more quickly from these kinds of hurricanes. It’s central to the question of whether I want to live in Houston. If we’re going to make it in the 21st century, we’ve got to be a place where the best and brightest people work at the cutting edge of knowledge, where people who can live anywhere want to live.”

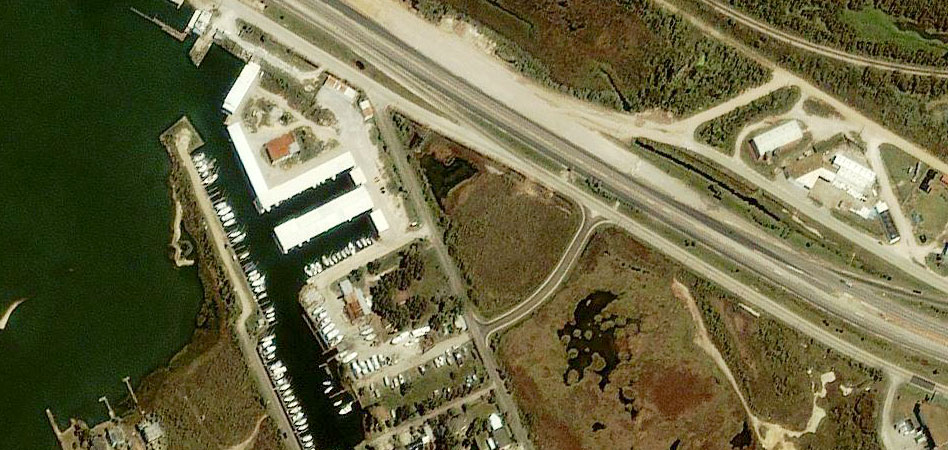

Galveston Causeway before Hurricane Ike (Copyright © 2008 GeoEye)

Galveston Causeway after Hurricane Ike (Copyright © 2008 GeoEye)

Economic problems and city programs

Rapid cleanup and recovery after a storm such as Ike is important for Houston to maintain a positive image with outside investors, so they don’t start to see it as a risky, hurricane-prone place, said Barton Smith, an economics professor at the University of Houston and director of its Institute for Regional Forecasting.

“We know Houston’s energy economy goes up and down,” he said. “My concern is that if the economy gets weaker over the next six months, that will be, in the minds of many, due to Ike. There could be a more permanent stigma associated with Ike than Houston really deserves.”

In any event, Smith said he is concerned that the Houston area is in for hard times in 2009, with the possibility of job losses on the near horizon if worsening economic conditions evolve into a major recession.

Based on experiences in the U.S. and elsewhere during past economic downturns, that could mean some city governments assign a lower priority to municipal sustainability initiatives, such as the energy-saving and related measures that Houston Mayor Bill White and some other Texas mayors have been introducing, he said.

“There’s evidence that environmental quality tends to be a luxury good,” Smith said. “When people are doing well, they feel they can afford it and are willing to pay the price. When things don’t look so good and you’ve just lost half of your retirement savings in your 401k account or lost your job, the environment is something you put on the back burner.”

The public’s support for measures to combat global warming may wane because of the recent reduction in gasoline prices from their record levels of just a few months ago, which were driving public sentiment for greater energy independence and for reducing energy consumption, he said.

“They had a kind of natural marriage. You didn’t have to believe in global warming to think you had to reduce dependence on fossil fuels.”

Smith praised White’s decision in October to get ready for any additional economic erosion with plans for possible delays in some infrastructure spendingso that more severe measures such as layoffs and sweeping budget cuts can be avoided.

“I don’t know if Mayor White has in mind any environmental initiatives or not,” he said. “But I think the environment will get lower and lower down the priority list. It’s human nature.”

However, Frank Michel, the city of Houston’s communications director, said he doubts the economic situation will have much effect on White’s continuing support for energy-conserving and associated sustainability programs.

“If anything, it would accelerate those things,” he said. “One small example is the program to replace most, if not all, traffic signals with LEDs (light-emitting diodes). They’re brighter, more visible, last longer and are twice as energy efficient.”

A “long list” of sustainability-related efforts is continuing, Michel said. Plans to delay spending “aren’t targeting any programs or services, just things we typically borrow money for. In general, environmental programs will not be much impacted.”

He noted that on Oct. 6 White announced an effort, in concert with other public and private entities, to plant a million trees in the Houston area over the next five years. The program was unveiled three weeks after Ike made landfall.

“We had planned to announce (the tree initiative) anyway,” Michel said, “but it takes on greater significance in the wake of the storm because so many trees were lost.”

Other sustainability initiatives announced by Houston officials recently include a competition soliciting citizen ideas for recycling tree debris resulting from Ike and a plan to install a solar energy system to supply part of the power electricity used at the George R. Brown Convention Center.

Environmental leader’s outlook

Ken Kramer

Ken Kramer earned a Ph.D. in political science at Rice, taught and carried out academic research on environmental policy and administration and has been the Sierra Club’s Texas state director for nearly 20 years. With that background, he has a special understanding of the tough challenges that frequently face environmental advocates in the state.

His initial response, when asked if Ike might prompt consideration of more policies oriented toward climate change and sustainability, had a sardonic edge: “Theoretically it could, but this is, after all, Texas.”

In a more serious vein, he quickly added, “I do think there is a good possibility that there will be more attention to sustainability issues as regards the Texas coast – by state officials and others – after what happened with Ike.”

One thing in particular will get the attention of state legislators when they convene next year – the large anticipated insurance payout as a result of Ike and the resulting impact on the Texas Windstorm Insurance program, Kramer said.

“The fact that the figures that have been mentioned are incredible has to give state political leaders some cause for thought about continuing, in effect, to subsidize development in some potentially very dangerous areas of the coast, where they could perhaps be hit by storms of various types with wind or flood or combined effects,” he said.

“My personal opinion is that when you’re talking big bucks and having an impact on the state budget and economy, that’s when people stand up and pay attention. I wish I could say there’s more attention to environmental concerns, but I think economic concerns are bigger with public officials.”

Ike could have more effect on public officials’ thinking than previous storms, because of its relatively wider area of impact, he said. “Also, it came only three years after Rita, impacting some of the same locales in different ways, when in many ways the recovery from Rita was not complete.”

There may also be more hesitation to rebuild in areas especially susceptible to storm hazards than after earlier storms, when the prevailing attitude was always to forge ahead, he said.

“If there’s a major amount of rebuilding of structures, it may be an opportunity to incorporate more current ideas about energy efficiency and renewable energy.”

Beyond such immediate questions, Kramer said Ike and other recent storms should sharpen Texans’ focus on climate change and their state’s emissions of greenhouse gases.

“One would hope, in a general sense, that concerns about global warming and sea level rise along the coast would translate into some acceleration of efforts at the state level to reduce the contributions of the state to global warming,” he said.

“Our philosophy is that you should start in your own backyard. I hope this will mean more of an emphasis on renewables and energy efficiency.”

Texas has taken important initial steps in recent years to improve energy efficiency, including legislative action in 2007 to boost from 10 percent to 20 percent the requirement for utilities’ use of efficiency improvements to meet growth in electricity demand, Kramer said.

“We may be poised to make more improvements,” he said, in part because Ike’s impacts, coupled with the assertion that global warming is accelerating sea level rise, could provide an effective argument for more ambitious energy-efficiency mandates.

Meanwhile, in a bid to augment the progress of the wind-power industry in the state, environmentalists are going to be pushing harder for state policies to encourage development of non-wind forms of renewable energy production, Kramer said.

“That movement is already under way.”