An announcement by NASA and NOAA about rising temperatures is consistent with a series of other recent reports that indicate the world isn’t making progress needed to escape the worst effects of global warming.

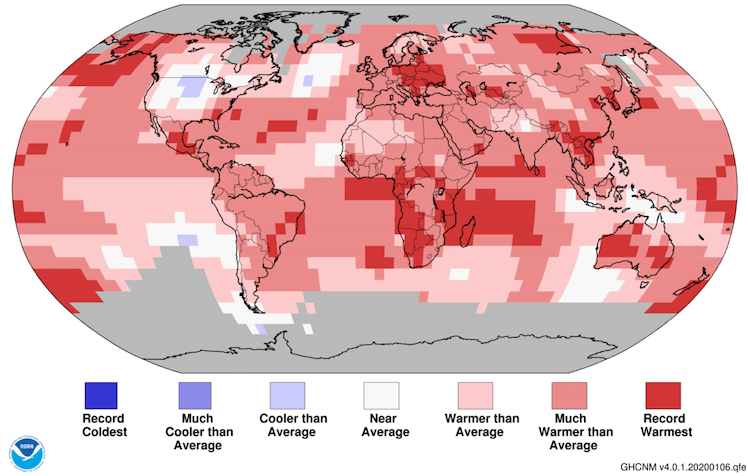

Average 2019 temperatures across most of the earth exceeded 20th-century averages, with many regions experiencing their hottest years on record. Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Scientists at two U.S. agencies made it official this week: As expected, they said their calculations showed 2019 was the earth’s hottest year on record and 2010-19 was the hottest decade.

The joint announcement by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) put a big exclamation point after a string of scientific reports and weather-related crises last year, which had individually and collectively underscored the urgent need for drastic action to avoid the worst projected impacts of climate change.

In a sweeping consensus, scientists have agreed for years that the warming trend documented anew this week by NASA and NOAA is being caused by humans’ creation of heat-trapping pollution in the use of coal, oil and natural gas.

The agencies’ latest annual calculations means 19 of the hottest years with temperature records have come in the past two decades. The past five years have been the hottest on record.

The NASA and NOAA conclusions were consistent with a December report by the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization.

The WMO said the planet’s average temperature is going up more quickly than scientists had thought – potentially putting it on track for an increase of two to three times the warming limits that nearly 200 nations agreed to strive for in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

“The planet is statistically, detectably warmer than before the Industrial Revolution,” said Kate Marvel, a NASA research scientist upon the release of the findings by that agency and NOAA. “We know why. We know what it means. And we can do something about it.”

That “something,” signatories to the Paris accord agreed, should essentially involve diverse actions to halt greenhouse-gas emissions from fossil fuels in the next half-century. The basic goal, the nations agreed, is to keep the continuing increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius and below 1.5 C if possible.

But with emission-cutting progress lagging since the Paris accord was reached, staying below its limits for extra warming is an increasingly daunting challenge.

In 2018, the world’s most prominent scientific body studying the issue, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (or IPCC), said keeping the planet’s temperature increase below 1.5 C will require eliminating 45 percent of greenhouse pollution in just the next 10 years.

The 1.5 C goal has increasingly gained favor with many scientists as the best way to avoid the most catastrophic impacts spinning off from a warming atmosphere – extreme events like stronger storms, more flooding, rising seas, worse heat waves and droughts, and more devastating wildfires among them.

Thirty-six nations experienced their hottest year on record in 2019, according to Berkeley Earth, an independent research organization. Extreme heat events were prominent in far-flung places – from Europe’s record-setting high temperatures to yet another round of killer heat in India (about 350 died as a direct result) to Australia’s raging wildfires at the year’s end and continuing into 2020.

NOAA reported last week that the number of climate- and weather-related disasters in the U.S. that caused at least $1 billion in damage doubled over the past decade, from 59 during 2000-09 to 119 from 2010-19. Last year’s 14 billion-dollar events had a $45 billion toll. The total economic damage from 2010-19 exceeded $800 billion.

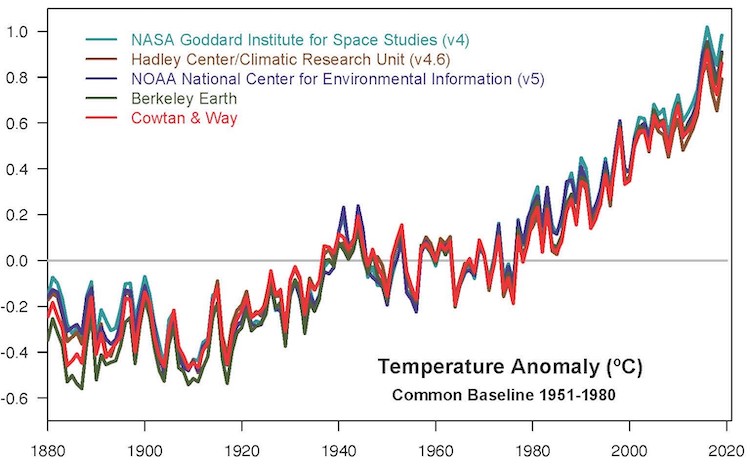

This NASA chart shows how the average global temperature differed from the mean for 1951-80, rising quickly over the past 40 years. The five lines represent statistical analyses by different researchers, including teams at two U.S. agencies (NASA and NOAA) and the U.K. Met Office’s Hadley Center. NASA noted: “Though there are minor variations from year to year, all five temperature records show peaks and valleys in sync with each other. All show rapid warming in the past few decades, and all show the past decade has been the warmest.”

Such details provided the cumulative basis for a dramatic warning by 11,000 scientists in November that humanity faces “untold suffering due to the climate crisis.”

“We declare clearly and unequivocally that planet Earth is facing a climate emergency,” they wrote in the scientific journal BioScience. “To secure a sustainable future, we must change how we live. [This] entails major transformations in the ways our global society functions and interacts with natural ecosystems.”

Not shifting fast enough

At the heart of such transformations, scientists have said for decades, and the Paris accord certified four years ago, is a profound and rapid shift of the world’s economy away from fossil fuels to eliminate greenhouse pollution.

Several reports last year, however, starkly underscored the fact that this shift is not happening nearly as rapidly as scientists say is needed to avoid the worst climate-change effects.

Under the headline “Another year, another record,” the WMO ’s Greenhouse Gas Bulletin announced in November that the average level of carbon dioxide, the primary human-released greenhouse gas, had reached a new record high in 2018.

“This continuing long-term trend means that future generations will be confronted with increasingly severe impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, more extreme weather, water stress, sea level rise, and disruption to marine and land ecosystems,” the organization said.

A day after that announcement, the U.N. Environment Programme released its annual Emissions Gap Report, which details “where greenhouse gas emissions are heading against where they need to be” to meet the Paris targets of 1.5 C and 2 C in extra planetary warming. Authors called their findings “bleak.”

A basic conclusion in the report was that the world must cut greenhouse emissions by 7.6 percent each year by 2030 to come close to meeting those targets. The Washington Post noted that 7.6 percent reductions, year after year, would be a pollution-cutting rate “currently nowhere in sight.”

Last week, the Rhodium Group, an independent research organization, announced its preliminary finding that U.S. greenhouse emissions fell by 2.1 percent in 2019 – almost wholly because of a drop in coal use – but were “still a long way off from the 26-28 percent reduction by 2025 pledged under the Paris Agreement.”

(President Donald Trump launched a process to withdraw the United States from the Paris pact, and his administration is in the process of rolling back numerous government initiatives to cut greenhouse emissions and boost fossil-fuel production and use.)

Despite an overall decline of nearly 10 percent in U.S. emissions from electricity production last year, “far less progress was made in other sectors of the economy,” the Rhodium report said. “All told, net U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions ended 2019 slightly higher than at the end of 2016.”

Alongside such documentation of unencouraging emission trends, leading scientists reported that the impacts of climate change are accelerating.

“There is a growing recognition that climate impacts are hitting harder and sooner than climate assessments indicated even a decade ago,” the authors of a U.N.-sponsored report, assembled by representatives of a variety of international science organizations including the WMO, declared in September.

“Climate change causes and impacts are increasing rather than slowing down,” the WMO’s secretary general, Petteri Taalas, said. “Sea-level rise has accelerated, and we are concerned that an abrupt decline in the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets will exacerbate future rise. As we have seen this year with tragic effect in the Bahamas and Mozambique, sea level rise and intense tropical storms led to humanitarian and economic catastrophes.”

Just three months after that grim assessment, worries about conditions in Greenland were aggravated with the publication of two new studies in December.

In one study, published in the journal Nature, 96 scientists reported that Greenland’s ice sheet is melting far more rapidly than scientists had thought – seven times faster than in the 1990s – threatening inundation of additional coastal regions inhabited by millions of people and worsening hazards from phenomena tied to rising sea levels such as storm surge.

In a second study, Norwegian and U.S. scientists analyzed past periods of warmer global temperatures, lasting thousands of years, when the Greenland ice sheet retreated. It appears there was “a critical survival threshold [for the ice sheet] within a few degrees of modern temperatures,” they concluded.

“Notably,” the researchers wrote in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “the critical temperature threshold for past [Greenland ice sheet] decay will likely be surpassed this century. The duration for which this threshold is exceeded will determine Greenland’s fate.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.