Ruth SoRelle, a medical and science writer for more than 40 years, covered the annual meeting of the AAAS (American Association for Advancement of Science) for Texas Climate News. The 2018 meeting was held Feb. 15-19 in Austin.

Ruth SoRelle, a medical and science writer for more than 40 years, covered the annual meeting of the AAAS (American Association for Advancement of Science) for Texas Climate News. The 2018 meeting was held Feb. 15-19 in Austin.

AAAS is the world’s largest general scientific society. The organization’s annual meeting is the premier science gathering in the United States, bringing together researchers from a wide range of fields to showcase some of the most important scientific work going on worldwide.

SoRelle covered a variety of science topics for the Houston Chronicle, explained them as chief science editor at Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine, and continues to write about them as an independent journalist.

Her reports from the meeting, which appear below this list:

- Plenary lecture by Texas Tech’s Katharine Hayhoe: When facts are not enough

- Scientific session: “Understanding and responding to climate-change denial”

- Scientific session: “Informing mitigation and adaptation options with the Climate Science Special Report”

- Scientific session: “Preparing for floods and droughts with NASA’s ‘scale in the sky’”

- Meeting discussion: A derailing of climate-data sharing and availability under Trump?

- Scientific session: “Involving stakeholders to improve outcomes – lessons from the climate centers”

- New study: Materials like personal care products are now a dominant source of air pollution [Read her detailed report for TCN about the study here.]

+++

Plenary Lecture by Texas Tech’s Katharine Hayhoe: When facts are not enough

Climate scientist and communicator Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Tech University, named to several prominent lists of the world’s most influential thinkers, likens climate change to smoking.

“The best metaphor I can think of is, we’ve been smoking a pack of cigarettes a day since the beginning of the industrial revolution. There is some permanent lung damage, but at the same time, when is the best time to stop smoking? Now. And if you can’t stop now, tomorrow,” she said in a plenary lecture at the AAAS annual meeting.

In it, she argued that climate scientists should advocate fact-based solutions to the problems they identify, just as physicians do.

“Every additional ton of carbon dioxide we produce carries with it a cost. And so, in the same way, every time we can reduce [emissions], it reduces the risk that we face in the future. Some change is inevitable. But a large amount of serious and even dangerous impacts can be prevented by acting now.”

People who don’t accept the reality of climate change are a scientist’s worst nightmare, she said.

“What happens when facts that are the very lifeblood (of a scientist’s career) are not enough? We are here because we love science,” she said.

Katharine Hayhoe

While the wheels of science grind slowly, she added, eventually they grind out agreement on topics that have been in dispute before.

Scientists tend to assume that communicating the facts underlying that long-sought agreement is enough.

“When we see headlines that say, ‘Don’t worry about sea level rise, it’s just erosion.’ Or, ‘What is the best temperature for a planet anyway? I think we’d like it to be a little warmer.’ Or, ‘Oh sure, the climate may be changing, but it’s not carbon dioxide that’s causing it.’ Our instinct is to say, ‘If they just knew the facts, certainly they would change their minds,’ because that’s what we do. Right now, there’s no question when it comes to climate science. It is real, it is us, and it’s serious.”

But why should the public care if the global average temperature and sea level are high? Just as doctors advocate for and help patients who are ill, climate scientists should advocate for solutions to climate change, Hayhoe argued.

Imagine, she said, being a parent and taking your child to the doctor because she has a constant and increasing fever. After some tests, the doctor offers no diagnosis or advice, saying, “Oh, that is not my job. I can’t advocate.”

That’s not what we expect from our doctors, Hayhoe said. “We expect our physicians to be advocates for us, to walk with us, to explain to us, to help us understand and explore the options. We need our hearts to understand what’s in the hearts of others.”

Part of the opposition to understanding climate change is the fear of solutions, she said. And those solutions might have impacts on our way of life. Scientists need to say that the solutions are beneficial. “There are great solutions, but those impacts are serious.”

“What is the scientist’s role today?” she said. “I’m going to borrow some words from one of my favorite scientists, Jane Goodall, who, at the end of a long career in science, said, ‘It is only when our clever brain and our human heart work together in harmony that we can achieve our full potential.’”

+++

Scientific session: “Understanding and responding to climate-change denial”

Pope Francis’ 2015 climate encyclical speaks of a moral obligation to address climate change and protect the poor who are most hurt by it.

In contrast, President Trump has rolled back a number of Obama-era climate-change policies and initiated U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement.

Whether you agree with the pope (and others who call for action against climate change) or Trump (and others who scoff at it) depends less on your religious affiliation than your political party, say researchers who have studied the phenomenon of science denial.

The United States is the birthplace of organized climate-change denial and also home to the world’s only political party, the Republicans, that promotes such denial, said Aaron M. McCright, a sociologist at Michigan State University who studies how various factors influence the capacity to deal with environmental and technological impacts.

Climate-change denial began with the Republican Party in the late 1980s and early 1990s when, after the fall of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the right needed a new enemy, he said.

The U.S. conservative movement mobilized against environmental science and regulation, and climate-change denial may fade only when conservatives abandon their general anti-environmental stance, he said.

Pope Francis greets visitors in St. Peter’s Square at Vatican City, Rome

When Francis issued his encyclical, some thought it might influence conservatives to accept climate science and support climate action.

In fact, the encyclical had little effect on attitudes about climate change across the political spectrum, said Ashley Landrum, a social-cognitive psychologist and assistant professor of science communication in the College of Media & Communication at Texas Tech University, who studies how cultural values and worldviews influence people’s perceptions of science.

Those who already believed in it saw their belief validated, she said. Those who did not believe denied the pope’s authority to speak on such issues.

Did the pope affect his own credibility? she asked, and more importantly, is there hope that the climate problem can be resolved?

+++

Scientific session: “Informing mitigation and adaptation options with the Climate Science Special Report”

Last November, the U.S. Global Change Research Program, a federal initiative that dates to 1989 and comprises 13 agencies and institutions, issued its latest assessment of the current state of the science of climate change – the Climate Science Special Report.

Focusing particularly on the United States, it has a practical goal – “to serve as the foundation for efforts to assess climate-related risks and inform decision-making about responses,” the authors wrote.

The bottom line is simple, Don Wuebbles, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champlain, said at a panel discussion on the report, which he organized and moderated for the AAAS meeting:

“Our climate is changing, it is happening now and extremely rapidly. Because of human activity, the climate will continue to change over coming decades, no matter what we do, but we can affect how much it changes.”

“Climate change is real, it’s us, and it’s serious,” said Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. “Our report concludes there is no natural cause of the warming we are seeing,” but rather it is the result of human activities.

“It matters because it affects us,” she said.

Hayhoe cited Hurricane Harvey as a prime example. Over four days, Harvey dropped more water in the 13-county Houston area than ever before recorded in the continental United States, demonstrating the effects of global warming, she said.

While climate change did not cause the storm, it did increase its intensity and the rainfall that occurred, she said.

That appraisal reflects recent conclusions by scientists who specialize in studying tropical storms.

Last November, for instance, a leading researcher in the field, Kerry Emanuel of MIT, calculated that Harvey’s rainfall over Houston was a once-in-2,000-years event in the climate of 1981-2000 but a once-in-325-years event in the global-warming-influenced climate of 2017. Assuming some of the worst future climate projections materialize, the odds for Harvey-level rains over Houston become once in 100 years or 1 percent per year.

Hurricanes are not the only concern, Hayhoe said. “The California drought had an effect on agriculture, water resources and urban centers. To summarize, the drought is a microcosm of what we see happening. Climate change is interacting with and exacerbating those things like floods that already cause risks. We see this pattern happening across the world. The California drought is an important part of that. Climate change enhanced and extended the drought.”

Rapid reduction of carbon dioxide emissions is the only way to stabilize the average planetary temperature, said Benjamin Sanderson, project scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

To achieve the Paris Climate Agreement’s target of holding additional warming to no more than 2 degrees Celsius by 2100, “we have to reach nearly zero emission by the latter half of this century,” he said. Going below that would require removing CO2 from the atmosphere, a technology which is not feasible at this time.

“When I do my analyses, I look at cities, provinces, regions. And I look at what they will be like at 3 or 4 degrees Celsius warmer than they are today,” Hayhoe said. “We need to understand the minimum we have to prepare for, not matter what, and also we need to know what we can avoid by taking action now.”

For example, she doesn’t expect more hurricanes, but she and colleagues do anticipate their character to change – more rain, more storm.

How many people will be affected and how many buildings, roads and dams?

“Sea-level rising will bring a new paradigm,” she said. Some so-called “nuisance” floods when high tides inundate city streets are already occurring in the eastern half of the U.S., a phenomenon that will make some neighborhoods unlivable in the future.

+++

Scientific session: “Preparing for floods and droughts with NASA’s ‘scale in the sky’”

A Lubbock cotton farmer wanted to know if Texas has groundwater regulation. It was a very pertinent question – cotton farming in West Texas has long depended on irrigation with water taken from the Ogallala Aquifer, but that underground supply is diminishing as pumping exceeds replenishment with rainfall.

Bridget Scanlon of the University of Texas said she told the farmer: “Texas does have groundwater conservation districts, and they have managed depletion in the Ogallala Aquifer.” It is self-regulating. If it gets down to a thickness of 30 feet or less, we cannot deplete it any more and [agriculture in the region] goes to dry farming or range land.”

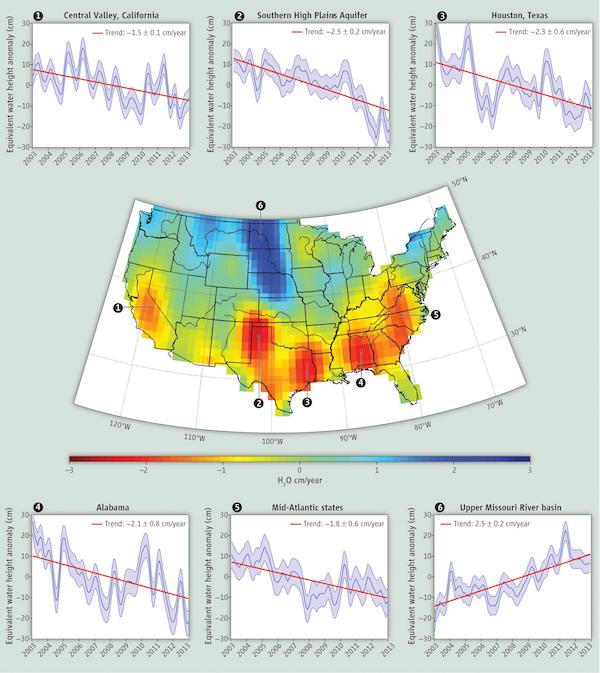

Texas’ drought-flooding cycle, which affects various regions of the state and scientists expect climate change to magnify, seems made for the attention of GRACE, NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment mission, a satellite-based remote-sensing effort that began in 2002. GRACE monitors variations in groundwater supplies around the world. Along with its other uses – cities like Houston, for instance, rely on groundwater as well as surface-water supplies – groundwater is a traditional backup for water supplies during extended periods of drought.

Compared to seven other models of measuring global water storage, GRACE is more likely to estimate the extremes in water storage and thus also the rate of sea-level rise, another concern because of a changing climate. As a giant “scale in the sky,” it measures the total amount of water (snow, surface water, groundwater and soil moisture) that enters or leaves a region each month.

“GRACE is better at modeling the extremes,” said Scanlon. Other models help understand different parts of the water cycle, she added, warning that experts should not rely on single models to understand it because the world faces an increasing need to adapt water use to trends in its availability.

Michelle Miro of the University of California at Los Angeles is attempting to scale down GRACE data to understand water use and need in the Central Valley of her state. While the area’s agriculture relies on a surface-water infrastructure of canals delivering water from Northern California, drought conditions force it to dip down deeper to the groundwater.

A map and charts based on GRACE data show areas where groundwater supplies diminished or grew from 2003-12. Much of Texas saw major losses over that period.

A recently signed state law regulating groundwater use is a paradigm shift that won’t be achieved until 2040. Miro hopes GRACE can provide necessary information, but the technique has low spatial resolution. Using equations derived from physics could help make the findings more specific, or researchers could achieve it by extrapolating known data points and melding those with GRACE information.

Jay Famiglietti of California Institute of Technology, in presenting his data, noted that as population has grown in the Pakistan-India region, the need for efficient water use has become apparent.

Faisal Hossain of the University of Washington is using data from GRACE to help Pakistani farmers in decision-making. Hossain wondered if the GRACE satellites could help. Combining data from GRACE and other missions to measure water across the globe, he runs the information through a model to understand water balance in the region – essentially, the flow of water in and out.

Text messages to individual farmers who have signed up for the program tell them whether their crops need irrigation during that two-week period. The result has been a 40 percent saving in irrigation water among the 80 percent of farmers who use his service. Farmer income has doubled because of a corresponding increase in crop yield.

Satellites such as those deployed for GRACE can help solve many complex challenges in water management in the developing world, said Famiglietti. But that requires a two-way, long-term strategy implemented by both researchers and stakeholders.

“User-inspired is not user-ready,” he said.

+++

Meeting discussion: A derailing of climate-data sharing and availability under Trump?

President Donald Trump has often expressed hostility to climate science and its crucial conclusion that manmade global warming poses a variety of threats.

Trump’s administration has often acted in ways that are consistent with those views. An international coalition of researchers and activists documented cases of references to climate change being “systematically removed, altered or played down on websites across the federal government,” the New York Times reported in January.

Even so, fears that scientists’ past attempts at sharing climate data and making it widely available would be derailed completely in the Trump era may be overblown, some researchers at the AAAS meeting said.

All final research products funded by the federal government have to be stored in a federal repository, and one questioner in the discussion following a talk worried that such databases could be corrupted.

That, said other scientists, would be hard to accomplish. All the original researchers have their own work on file. Many universities have redundant copies of the final products.

“There was an awareness of the need to take extra steps” to safeguard data, one researcher said.

+++

Scientific session: “Involving stakeholders to improve outcomes – lessons from the climate centers”

Three scientists, a local emergency manager, a line manager for a rural electric company and a sixth-grade elementary teacher walked into a meeting of the appropriations subcommittee of the Oklahoma Legislature, seeking funds for climate monitoring.

The emergency manager told the lawmakers that climate information helped him save lives during a weather incident in his community. The line manager discussed how access to climate information changed the way his company transmitted electricity, and the sixth-grade teacher talked about the lonely child who became a leader when he was given charge of a climate project.

“The gentlemen in the Legislature were in tears by the end of that talk,” said Renee McPherson, a climate scientist at the University of Oklahoma and one of the speakers at this AAAS session. “The three scientists said, ‘That’s our presentation.’ And each member of the subcommittee said, ‘Where do we send the check?’”

“Science is about people,” she said. “How can we make it about and for the people it is to serve?”

Eight regional climate centers set up by the U.S. Department of the Interior are designed to do just that, drawing in a host of resource-management partners to learn about the importance of climate change to them and brainstorm about how they can advocate preparations for the future. The aim is to help fish, wildlife and ecosystems adapt to climate change.

April Taylor, a sustainability scientist with the Chickasaw Nation who is based at the South Central Climate Science Center, housed at the University of Oklahoma, was another session speaker. Taylor’s job includes working as a liaison between Native American residents and climate scientists in Oklahoma, New Mexico, Texas, and Louisiana.

April Taylor (center, with hands folded) met tribal stakeholders in Louisiana at the first climate-training session for tribal representatives that was held in that state by the South Central Climate Science Center.

Tribes’ local monitoring of air and water quality means they are collecting their own data and own it, she said. There are a lot of opportunities to help them build capacity as they contribute to broader understanding by their traditional observation of the landscape and how and when things change.

Aaron Fournier, a law student at the University of Oklahoma, said the South Central Climate Science Center hosted there comprises representatives of a diverse group including the Chickasaw and Choctaw nations along with academic partners such as Texas Tech and Louisiana State universities.

The center, he said, employs more than 60 people from a variety of scientific disciplines along with others such as graphic designers.

Michelle Staudinger, science coordinator for the Northeast Climate Science Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, offered an example from that region of the kind of work that goes on at the eight centers.

She and her group developed a planning document that described the importance of climate information in comprehensive wildlife conservation strategies for the next decade, as well as other needs.

Staudinger said hoped the guides would help with writing and revising climate-change documents across the 22 states.

But Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech and the session organizer, offered a cautionary note. In light of climate-change projections, predicting the future by looking at the past is fraught with disaster, she warned.

“It’s like driving down the road looking into the rearview mirror,” she said. “If you are heading into a curve, who knows where you will end up? We are already on the curve in climate science and we have to figure out how to successfully negotiate the curve. That means we have to be talking to people and asking if we are all going to be OK in a time of such massive change.”

+++

New study: Materials like personal care products are now a dominant source of air pollution

In 2016, the U.S. Global Change Research Program issued a major report synthesizing scientific findings about the impacts of climate change on human health. One key conclusion involved a stark warning about ground-level ozone, a respiratory hazard that forms when various chemical air pollutants react, and historically the nation’s leading air-quality problem:

Climate change will make it harder for any given regulatory approach to reduce ground-level ozone pollution in the future as meteorological conditions become increasingly conducive to forming ozone over most of the United States. Unless offset by additional emissions reductions, these climate-driven increases in ozone will cause premature deaths, hospital visits, lost school days, and acute respiratory symptoms.

A view of smoggy Los Angeles in 2010, captured by scientists from a research aircraft.

A new study, discussed at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science, revealed another complication in the effort to reduce health-threatening air pollution:

The researchers surprisingly found that as tailpipe emissions dwindle with increasingly rigorous controls, volatile chemical products that include pesticides, coatings, printing inks, adhesives, cleaning agents and personal care products now make up about half of volatile organic compounds (VOC) emissions from fossil fuels in industrialized cities, contributing to continuing air pollution problems.

At the AAAS annual meeting in Austin, leaders of the mammoth project described the painstaking work that went into identifying the gap in the inventories of urban volatile organic compound sources – a gap that had only widened as controls on air pollution from transport- and fuel-related sources reduced emissions.

Read a detailed report on the study in TCN.

+++++