Kemp’s ridley sea turtle nesting on Padre Island. Of the world’s seven species of sea turtles, Kemp’s ridley is one of two that are internationally listed as “critically endangered.” Another species is “endangered” and two are “vulnerable.”

By Melissa Gaskill

Texas Climate News

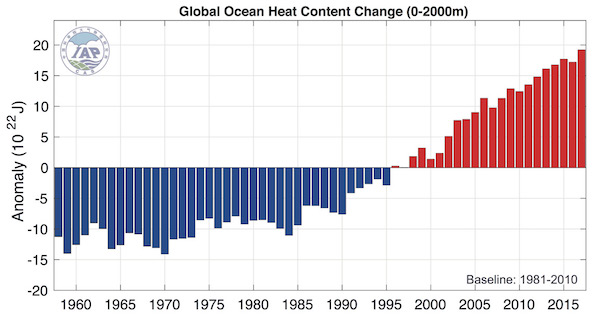

The past few years have seen the warmest average temperatures on record for the global ocean, with higher temperatures in most regions of the world.

Hotter seas have a number of consequences: increased bleaching and mortality on coral reefs, larger hypoxic zones with lowered oxygen levels and shifts in the timing and abundance of prey for marine species. Warmer temperatures also could make reproduction increasingly challenging for sea turtles, including those that nest on Texas beaches.

Like most reptiles, sea turtles lack sex hormones. An embryo develops into a male or female based on incubation temperature, a phenomenon known as temperature-dependent sex determination. For most sea turtle species, males and females develop in equal proportions at 29 degrees Celsius (84.2 Fahrenheit). Lower temperatures produce more males, higher temperatures produce more females. Around 35 C (95 F), embryos start to die.

Up to a point, more females mean more eggs and, therefore, more sea turtles. But scientists don’t know how many males are sufficient to sustain a population.

“It is a concern,” says Donna Shaver, chief of sea-turtle science and recovery at Padre Island National Seashore in South Texas. “Eventually, of course, mating opportunities become limited because there are not enough males.”

A recent study in Current Biology found that green sea-turtle rookeries on the northern Great Barrier Reef of Australia have produced primarily females for more than two decades, making complete feminization of that population possible in the near future. The authors note that average global temperatures are predicted to increase 2.6 C (4.6 F) by 2100, putting many sea turtle populations in danger of high egg mortality and female-only offspring production.

Researchers from Florida Atlantic University note a similar trend in Palm Beach County, Florida, where 97 to 100 percent of hatchlings since 2002 are female.

Most sea turtles nesting on the Texas coast are members of the critically endangered Kemp’s ridley species; 353 Kemp’s ridley nests were recorded in Texas in 2017, 219 of them at Padre Island National Seashore, breaking previous records of 209 in Texas in 2012, and 117 at the Seashore in 2009 and 2011.

For this species, the pivotal temperature, or point at which males and females develop in equal proportions, is thought to be 30.2 C. Kemp’s also may survive at a slightly higher nest temperature than other species. That doesn’t mean the species is out of hot water, though, pardon the pun.

A graph produced by the Institute of Atmospheric Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences shows rising ocean temperatures since the 1950s – a trend that U.S. and other scientists have also charted. Each bar shows the annual mean temperature’s difference from a 1981-2010 baseline.

Thane Wibbels, biology professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has monitored temperatures at Rancho Nuevo, on the Gulf coast of Mexico, since 1998. The primary nesting beach for the Kemp’s ridley, this location sees upwards of 25,000 nests per year. Wibbels also monitors other beaches in Mexico and at Padre Island National Seashore. While data from the Texas beach do not go back to 1998, in general temperatures there tend to mimic those at Rancho Nuevo.

“We are seeing significant increases in beach temperature and temperatures in egg corrals, which equates to higher production of females,” Wibbels says. Strong indications are that Rancho Nuevo is producing three females to every one male. In the egg corrals, which are simply protective fences constructed around nests on the beach, temperatures have been upwards of 34 C and 35 C, he adds, which will produce only females (and, eventually, lead to embryos dying).

“Quite frankly, it means more eggs in the near future, as long as there are enough males,” Wibbels says. “The question that we don’t have an answer to is, when don’t we have enough males?”

Some data suggest Kemp’s ridleys are nesting a little earlier. This species practices mass nesting, where several times per season hundreds or thousands of females come ashore to nest at once. The event is known as an arribada. In 2017, Wibbels reports, arribadas occurred earlier than usual.

The Current Biology paper notes that sea turtles theoretically can adapt to climate change by changing their choice of nesting grounds or adjusting timing of nesting. But they are unlikely to be able to make such changes quickly enough; sea turtles take at least 15 years to reach sexual maturity, and have strong natal homing, with females returning to nest at the beach where they were born. Temperatures are predicted to increase by several degrees Celsius in only a few turtle generations.

In addition, sea turtles nest two or three times per season, Wibbel points out, and even if they lay one nest earlier, when temperatures are cooler, their second and third nests will still experience warmer temperatures and produce mostly females.

“This is happening so fast that we don’t have the generations for [adaptation] to happen,” he says. “From an evolutionary standpoint, sea turtles could compensate on geological time scale, but not on the time scale we’re seeing. We really have to keep an eye out and monitor it closely before we have an extreme sex ratio situation, or temperatures so hot that we start getting mortality and decreased hatch rates.”

Scientists can take action to counter some of the effects of higher temperatures, including screening nests from the sun and cooling them with water. The FAU study also found that temperatures normally producing females can produce male hatchlings given high sand moisture. These methods have been used successfully on various nesting beaches, and the infrastructure is already in place at both Rancho Nuevo and Padre Island, where eggs are brought into an incubation facility where the temperature can be controlled.

“We don’t want to get into continual manipulation,” Wibbel cautions, “But, at the same time, we are in good situation to monitor and take the best conservation strategy available to produce optimal, healthy hatchlings of an appropriate sex ratio.”

Sea turtles make important contributions to their marine ecosystems. For example, green sea turtles crop sea grass beds, increasing their productivity, and contribute to the flow of nutrients.

“Sea turtles may have roles we haven’t even thought about yet,” says Shaver. “As their numbers get closer to what they have been historically, those may become more obvious.” In addition, they support ecotourism in many places around the world.

+++++

Melissa Gaskill is a Texas Climate News contributing editor. An Austin-based writer, Gaskill’s work has been published by Nature News, Scientific American, Wildflower, Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine, Smithsonian, Men’s Journal and others. She received a bachelor’s degree in zoology from Texas A&M University and a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin.