Amanecer meeting in El Paso. Courtesy Amanecer People’s Project

After its wide-ranging green ballot initiative flopped in a citywide election on May 6, 2023, a group of El Paso student activists dedicated to environmental preservation and climate justice resurfaced with a new name, broadened membership ambitions and attention to additional community concerns including public-school issues.

After the election loss, for example, a still-continuing campaign to install air conditioning in 24 schools, which now only have evaporative “swamp coolers,” started with a “listening canvass” in which members went door to door to learn about residents’ civic concerns, said Ana Fuentes, the organization’s executive director.

The swamp coolers “used to work but with increasing temperatures, children are in hotter classrooms,” she said. While waging its continuing Escuelas Frescas (“Cool Schools”) drive for air conditioning, the group became involved in public discussions and debates about related issues – school closures, a possible school bond issue (which could pay for air conditioning) and an El Paso Independent School District board election this coming May.

It all started with a climate action campaign and a different group name.

From Sunrise to Amanecer via election loss

The organization, originally known as Sunrise El Paso, was reborn as Amanecer People’s Project (amanecer is Spanish for sunrise) after the ballot initiative failed. Amanecer decided to amplify its influence by expanding recruitment to members of all ages and backgrounds – not just college-age students, as before. Since the 2023 election, Amanecer membership mushroomed by more than 800% as the organization focuses on direct action in underserved communities.

Amanecer bills itself as a “community advocacy and power-building organization that aims to shift decision-making power away from polluting elites and place it back in the hands of the community.”

Sunrise El Paso had been affiliated with the Sunrise Movement, a nationwide youth group prioritizing climate justice that has promoted the Green New Deal, an ambitious collection of proposals to combat climate change, create jobs and reduce inequality.

(The Green New Deal, as such, never became law, but there was disagreement about whether and to what extent Biden administration climate initiatives resembled it. For their part, Donald Trump and other critics often use the name Green New Deal to attack the prior administration’s climate and energy policies.)

Though now disengaged from Sunrise, Amanecer retains the same goals and ideologies, but with the freedom to pursue a broader demographic.

Ana Fuentes, executive director of Amanecer People’s Project. Christian Betancourt/El Paso Matters

“We know that the only way to win is to bring as many people as possible into the movement,” said Fuentes, 28, an El Paso native. “So, we want to open up the membership to all El Pasoans of any age who are committed to climate action and sustainability.”

To that end, Fuentes said she was pleased with the attendance at the Amanecer launch event. “Importantly, there were attendees of all ages – including families and older community members” – “the start of a powerful new phase.”

Amanecer’s precursor, Sunrise El Paso, comprised about 20 University of Texas at El Paso students, including Fuentes, when it joined with Ground Game Texas, an issue-focused organizing project backed by prominent Democrats, to spearhead the El Paso Climate Charter and get it on the May 2023 ballot. Known as Proposition K, the charter principally sought to codify emission reductions, renewable-energy investments and protection of water from fossil-fuel projects. It clearly charted a course toward green energy and away from hydrocarbon-fueled power generation.

Though Sunrise El Paso applied equal measures of enthusiasm and hard work in hatching the climate charter, Prop K soon ran into a buzzsaw of troubles. At 2,500 words, it drew criticism for being too long, and its mashup of multiple environmental policies struck some as unfocused. Prop K also bore a passing resemblance to another, less comprehensive El Paso renewable-energy initiative, Proposition C, that voters had approved only six months earlier. Observers speculated that the existence of Proposition C may have sown confusion about Proposition K, undermining its chances for success.

An alliance of pro-business and fossil fuel-based energy groups quickly moved in for the kill. Led by the Consumer Energy Alliance, an oil industry-backed organization that opposes government regulation of carbon emissions, the Prop K adversaries responded with a blistering multi-media campaign featuring an avalanche of mass mailings and TV ads designed to resonate with the city’s older, more conservative citizens – a group with reliably high voter turnout.

With a reported outlay of $1 million to $2 million, the forces arrayed against Prop K outspent Sunrise El Paso by as much as 20-to-1, according to Fuentes.

“Unfortunately, the nearly $2 million that was spent by our opposition, and the fear-mongering that came with it, really mobilized an electorate that is not representative of El Pasoans,” Fuentes said. “And [the opposition] had so many resources to scare the community into voting against their own self-interests.” When the ballots were counted, the El Paso Climate Charter had gone down in flames, with 82% having voted against it.

While the climate-charter opposition celebrated the lopsided result as a vindication of their positions, Fuentes argued that it was a blizzard of misleading information that doomed the measure. The anti-Prop K campaign had included claims that the climate charter was the work of outsiders, which Fuentes refutes. The pro-proposition campaigners were “all born-and-raised El Pasoans going to school here and wanting to stay here in El Paso,” she said.

The El Paso Chamber of Commerce, central to the climate-charter opposition, commissioned a study showing that Prop K would radically shrink El Paso’s electricity supply and hemorrhage half the city’s jobs, including massive layoffs among police and firefighters – assertions Fuentes characterizes as “an absurd tactic of disinformation. These claims came from the opposition’s purposeful misinterpretation of the policy,” she said.

The Chamber seized on the criticism to reiterate its message. “Local proponents seem incapable of offering a clear argument for the charter except to criticize the data commissioned by the Chamber,” said its CEO Andrea Hutchins in an interview with El Paso Matters. “The repeated assertion that the [Chamber] study is biased, rather than defending solid policy, is a clear indicator to us that K cannot be defended on its merits.”

But researchers at IdeaSmiths, an Austin-based energy consulting firm with tangential ties to the University of Texas at Austin, found fault with much of the El Paso Chamber’s assertions. The firm debunked the anti-Prop K claims of job losses and power shortages, describing them variously as “egregious” and “unrealistic.” Still, Sunrise El Paso was ill-equipped to transmit that message and mount a proportional media blitz because the group “did not have the millions of dollars that Big Oil used” for its campaign, Fuentes said.

Demographics and public opinion

Despite Prop K’s defeat, Fuentes nevertheless remains optimistic about getting Amanecer’s messaging to a more receptive audience as the organization continues in its all-ages incarnation.

“The electorate is disproportionate – they’re older and whiter than our general population,” she said, noting that the 12% of El Pasoans who are 65 or older represent about 45% of the voting public. “These are the folks who will not live through the worst of the climate crisis.” She believes the city’s majority populations harbor the potential to overcome the Prop K setback.

More than 82% of El Pasoans are Hispanic, and 64% of the city’s population is 20 to 64 years old, with the biggest group concentrated in the 20-44 age range – a demographic generally regarded as more open to climate science and renewable energy solutions.

“From our experience we know that climate action does resonate with El Pasoans – if you talk to them about our lack of reliance on solar energy, our water scarcity and the need to protect our water,” Fuentes said, warning that new, water-intensive oil-drilling projects in the nearby Permian Basin carry the risk of diverting water from an already desiccated El Paso.

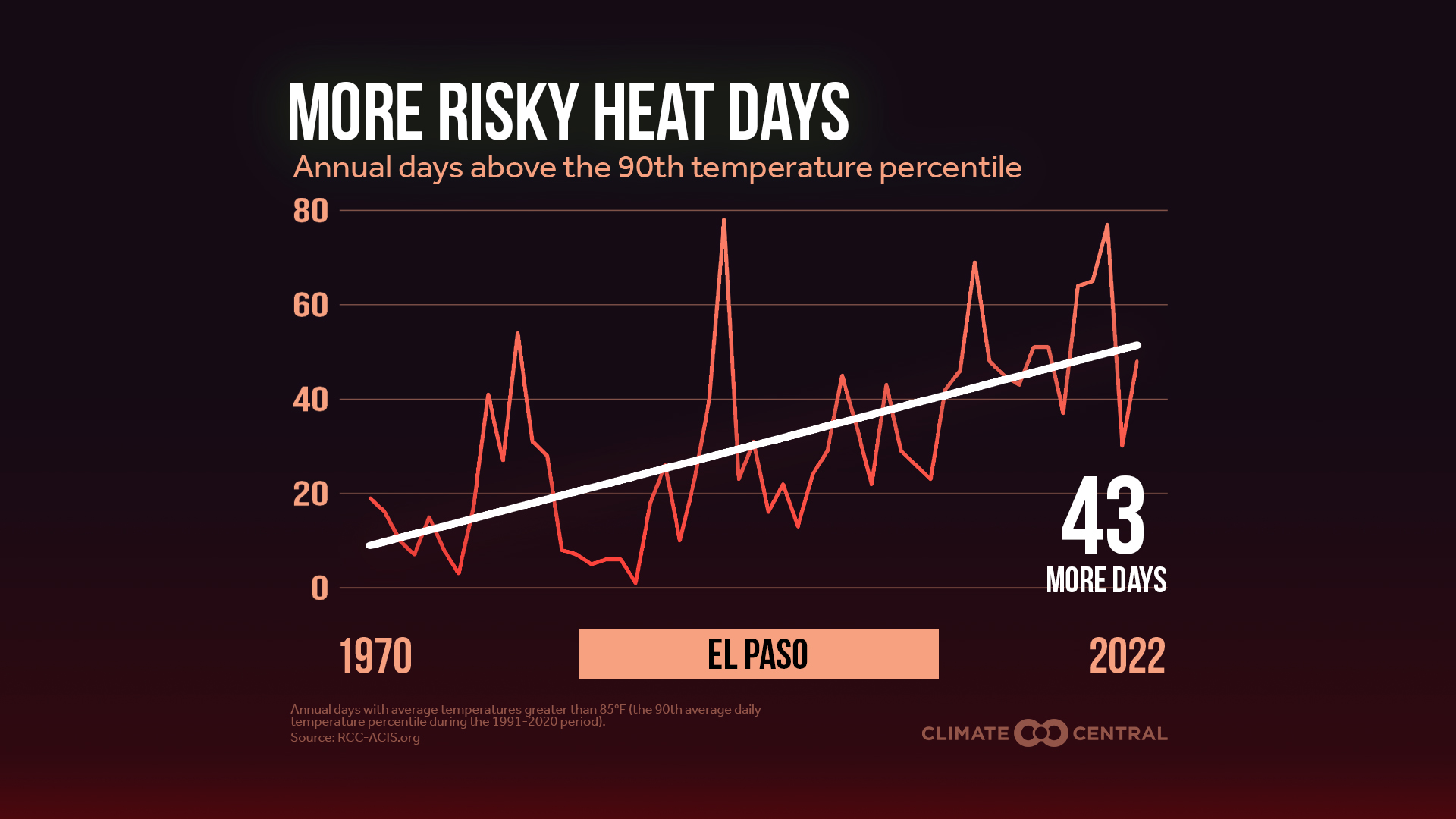

Climate Central, which produced this graphic, is a nonprofit science and communications organization.

Concerns about the more and/or stronger dust storms have increased in the city amid projections of warmer, even drier conditions in the desert Southwest as climate change unfolds.

The latest in a recent series of dust storms to hit El Paso brought these local headlines last week:

Dust storm wreaks havoc in El Paso, residents express frustration

String of dust storms pose risk to physical health, AC units

‘It feels apocalyptic’: Dust storm blows through El Paso

The television station KFOX14 reported on March 18: “Another dust storm swept through the borderland on Tuesday, bringing high winds and significantly reduced visibility, leaving residents frustrated with the persistent weather conditions. […] Many locals, who have lived in El Paso for years, believe the weather has worsened over time.”

Just days before that dust storm hit, Amanecer was seeking to draw attention to possible links between such storms and man-made climate change in an Instagram post about an upcoming orientation meeting.

One slide on that post quoted an article published in January in the British scientific journal Lancet Planetary Health: “The frequency and intensity of sand and dust storms has intensified in many world regions due to climate change and anthropogenic [human] activity.” Such storms, the article said, pose a growing public health threat that demands more study to “support policy action.”

The dust storm last week was so bad, it compelled Amanecer to hold a weekly work meeting as a virtual, instead of in-person, gathering, Fuentes said.

Electricity production and the future

El Paso Electric, the utility that supplies electricity to the city and surrounding region, has been an object of Sunrise El Paso’s and then Amanecer’s criticism because of its reliance on fossil fuels in the fourth-sunniest city in the U.S. While the power grid that serves most of Texas outside of El Paso receives 37% of its electricity from wind and solar farms, El Paso Electric was generating just over 5% of its electricity from solar as late as 2022, and showed no wind energy in its renewables portfolio.

The solar-power scenario is changing, however, as electricity from the utility’s huge new Buena Vista solar farm surges into the grid. In June 2023, EPE switched on the 900-acre facility, located outside Chaparral, New Mexico, unleashing up to 120 megawatts of photovoltaic power.

El Paso Electric has committed to producing 100% carbon-free power by 2045, a goal that would seem to be in alignment with those of Sunrise El Paso and Amanecer. But the utility joined the opposition to Prop K at least partly because of the climate charter’s stipulation to examine converting the utility to city ownership, a move opposed by the company and other anti-Prop K factions. (The utility is currently owned by a JPMorgan Chase investment fund, which bought it in 2019.)

Meanwhile, Amanecer has been mapping a strategy to determine how best to guide El Paso toward a more sustainable future while taking action to address the needs of overlooked populations.

A social media post promoting Amanecer’s launch of its Escuelas Frescas campaign on Instagram.

“Through our canvassing work, we identified 22 schools in the El Paso Independent School District with old, ineffective swamp coolers,” Fuentes said. Amanacer has called for EPISD to use available federal funding from the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act – a law that provided for hundreds of billions in spending on climate-related, clean-energy and other initiatives and projects – “to update these inadequate cooling systems and ensure our children have access to healthy, sustainable classrooms, ” and address other school needs, she said.

School-district politics isn’t the only challenge facing that effort. Uncertainty clouds the federal Inflation Reduction Act’s future, as its continuing rollout faces strong opposition from Trump and many congressional Republicans. The Brookings Institution, a prominent, nonprofit think tank in Washington, assessed the law’s future in January:

Recent attempts by Republican lawmakers to partially repeal or hinder the implementation of the IRA suggest that there may be specific sections of the IRA that are particularly vulnerable under the [Trump] administration. The slimness of majorities in the Senate and House could present challenges for Republican lawmakers in creating a coalition for a full repeal of the IRA, as incentives in the IRA have benefitted Republican constituents. However, the IRA remains vulnerable as congressional coalitions are not needed for executive action that challenge the implementation of the IRA.

Fuentes said Amanecer members understand the demands of the advocacy work they have undertaken as the group has evolved from a university student endeavor to one with a broader membership.

“We just want to reemphasize the importance of building community power and talking to our community members about climate change and solutions to climate change because the solutions and the vision and the narrative can so easily be co-opted by the opposition, as we learned from Proposition K,” Fuentes said. “So, it is on us to build relationships and trust with El Pasoans so they know the reality that we’re living through, and what we all can do about it.”

John Kent, an independent journalist based in Fort Worth, is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News.

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.