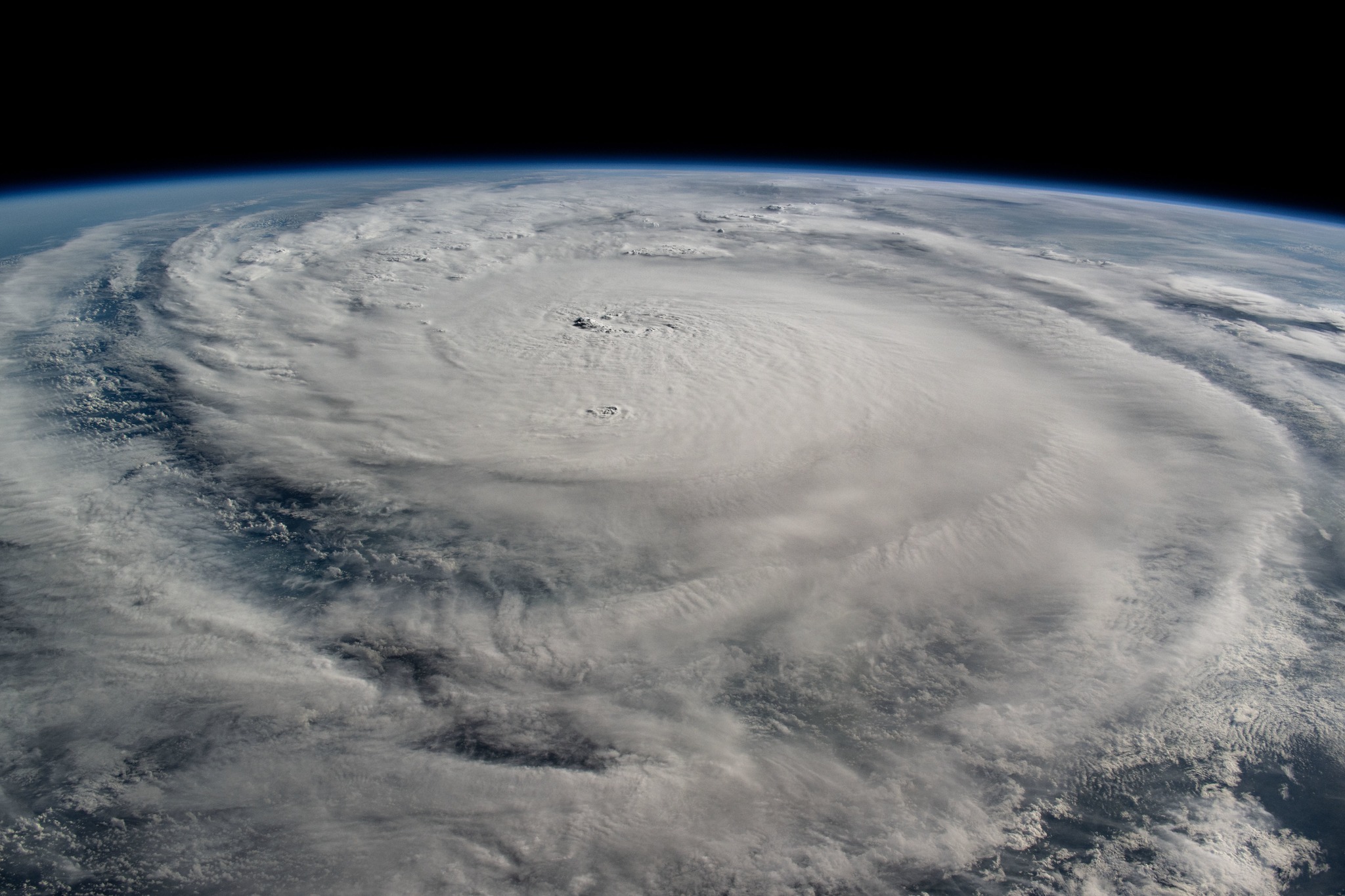

Hurricane Milton after reaching Category-5 status. NASA

After rapidly intensifying Hurricane Harvey brought catastrophic flooding in 2017 to Houston and other locations in coastal Texas, it was only a few months before scientists released calculations showing how much worse the rainfall was because of pollution-fueled climate change.

Hurricanes Helene and then Milton, coming less than two weeks later, demonstrated once again recently that rapid intensification of hurricanes is one of the most frightening manifestations of global warming.

As they had done following Harvey’s devastation, teams of scientists have announced several preliminary climate-attribution studies about Helene and Milton. All concluded that climate change made both storms more powerful than they would have been without humans’ continuing disruption of the climate system.

Scientists stress that global warming doesn’t cause hurricanes to form, but is making them more destructive in assorted ways. Researchers now regularly perform post-hurricane “attribution studies” – calculating how much climate change boosted a specific storm’s destructiveness.

Hurricane scientists say features of the changing climate including warmer ocean waters, warmer air and rising sea levels are making hurricanes worse in four key ways – winds and rainfall are increasing, storm intensification is speeding up and storm surge is being magnified.

Here’s a summary of attribution studies about Helene and Milton:

Helene

Helene’s monumental rainfall, especially destructive in mountainous regions of Western North Carolina and adjoining states, shocked residents unaccustomed to such deluges. By one expert’s calculation, the storm dropped more than 40 trillions gallons of water across parts of the Southeast.

The highest official precipitation total was 30 inches at one location in North Carolina. Radar estimates suggested totals up to 40 inches fell on higher elevations in the Appalachians. From there the rainwater flowed devastatingly to lower regions and caused flash flooding unprecedented in some areas.

Almost three weeks after Helene struck Florida, its death toll had risen to at least 225, with 95 of the fatalities in especially hard-hit Western North Carolina. At the worst point, an estimated four million people were without power. By one estimate, property damage from the storm totaled up to $250 billion.

Scientists from the U.S., United Kingdom, Sweden and the Netherlands teamed to do one of the attribution studies about Helene for the multinational World Weather Attribution initiative. It included these key findings about the hurricane’s wind speeds and rainfall:

The researchers examined rainfall in two places – a coastal region in Florida and an inland region in the Southern and Central Appalachians, which experienced three days of unprecedented rain before Helene’s arrival.

“In both regions,” they reported, “the rainfall was about 10% heavier due to climate change, and equivalently the rainfall totals over the 2-day and 3-day maxima were made about 40% and 70% more likely by climate change, respectively. If the world continues to burn fossil fuels, causing global warming to reach 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, devastating rainfall events in both regions will become another 15-25% more likely.”

Analyzing storms within about 140 miles of Helene’s track in a 1.3-degree C cooler climate (that is, in pre-industrial conditions), the team’s modeling showed that climate change was responsible for about a 150% increase in the number of such storms, with maximum wind speeds about 11% more intense.

Regarding Helene’s fast-growing intensity, fed by “record-hot sea surface temperatures” in the Gulf, the scientists concluded that those temperatures “over the track of the storm have been made about 200-500 times more likely due to the burning of fossil fuels.”

“Together,” the researchers concluded, “these findings show that climate change is enhancing conditions conducive to the most powerful hurricanes like Helene, with more intense rainfall totals and wind speeds. This is in line with other scientific findings that Atlantic tropical cyclones are becoming wetter under climate change and undergoing more rapid intensification.”

Scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California issued a more narrowly focused attribution report about Helene, which they cautioned was “preliminary and subject to change.”

They reported that their “best estimate is that climate change may have caused as much as 50% more rainfall during Hurricane Helene in some parts of Georgia and the Carolinas. Furthermore, we estimate that the observed rainfall was made up to 20 times more likely in these areas because of global warming.”

The Lawrence Berkeley team analyzed 24-hour rainfall totals from a set of precipitation estimates. “Clearly,” they wrote, “the storm slowed down, especially as it passed over the Carolinas and the storm total rainfalls are considerably larger than the 24-hour totals. As the wettest regions generally experienced a larger effect from climate changes, we may expect to find a larger human influence on Helene’s rainfall in some areas.”

The ClimaMeter organization – a Europe-based scientific consortium – did not attribute a specific portion of Helene’s power to human-driven climate change. But it concluded generally that climate change had contributed to the storm’s increased precipitation and wind-speeds. Storms like Helene are now 20% wetter over the Southeastern U.S. and up to 7% windier on Florida’s Gulf Coast than in the past, the group said.

Milton

Hurricane Milton exploded from tropical-storm status to Category-5, the strongest hurricane designation, in less than 24 hours as it churned toward the central part of the Florida peninsula’s west coast.

Its intensity decreased slightly to Category-3 by landfall, however, so its extreme rainfall, storm surges of up to 10 feet and high winds, while devastating, were not as dire as had been feared.

At least 33 deaths have been officially assigned to Milton, three in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula and 30 in Florida. The cost of property devastation has been estimated at more than $50 billion. Many of the deaths and much of the property destruction in Florida were caused by a related and record-setting tornado outbreak before the hurricane made landfall.

Just as with Helene, Milton’s explosive strengthening as it crossed the Gulf occurred over super-heated ocean waters that were at record levels or hotter. Building on their earlier research, scientists from the independent, U.S.-based research group Climate Central concluded that sea-surface temperatures in the region where Milton developed were made up to 400-800 times more likely by climate change in the preceding two weeks.

World Weather Attribution said it analyzed Milton too soon after the storm’s landfall – the next day – to have updated data necessary to perform computer modeling of the storm’s rainfall, as it had done with Helene. However, the organization said historical data showed that rain events like Milton are at least 20-30% more intense in today’s warming, post-industrial climate.

Using the same analytical method they employed with Helene, the scientists’ modeling of Milton showed climate change has produced about a 40% increase in the number of storms with the same intensity and a 10% increase in their wind speeds: “In other words, without climate change Milton would have made landfall as a Category 2 instead of a Category 3 storm.”

Another team of researchers – this one in the U.K. at the Imperial College London – duplicated the 40% intensity estimate using the same model. They added a calculation about financial losses: “We also estimate that nearly half (45%) of the loss in Florida of a Milton type can be attributed to climate change.”

The Imperial College researchers included this comment in their report regarding the super-heated Gulf waters that helped fuel Helene and Milton:

“[Regional climate changes] are more likely to be caused by decadal variations and less likely to be sustained or representative of global warming. It is for example very unlikely that the Gulf of Mexico will continue to warm relative to the globe at the current rate.”

ClimaMeter also weighed in on Milton with a brief conclusion that “Hurricanes similar to Milton have become up to 12 mm/day (up to 20%) wetter over South Florida in the present than they have been in the past.” The researchers said, however, that they had “low” confidence in that estimate “because of the exceptional trajectory” of this storm.

Non-linear impacts

In a recent blog post, Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist and climate policy expert at Texas A&M University, commented on an aspect of reactions to Helene’s devastating flooding in Asheville, N.C. and nearby areas: Nestled in the Appalachian mountains, far from Helene’s landfall in Florida, booming Asheville had been considered by some as a safe haven for avoiding the hazards of a changing climate.

Dessler observed:

While climate change does not cause hurricanes, we are certain it makes them more destructive. Humans have increased sea level, leading to more destructive storm surge, and a warmer atmosphere produces more rain.

Many people don’t understand how this will affect them.

They think it’s a long-term problem where small impacts accumulate over decades, eventually leading to significant consequences far in the future.

In reality, though, these increases in storm surge and rainfall push our physical environment beyond thresholds that infrastructure was designed to handle.

As a result, the impacts of climate change are non-linear: they are zero until you cross the threshold and then, suddenly, you are wiped out. This leads to headlines like this: “In decades, their home never flooded. Then in a flash, they were homeless.”

And there will be “indirect impacts” of more devastating hurricanes, he added, besides the direct destruction and death in flooded and wind-struck areas:

At best, insurance rates will go up. At worst, insurers will pull out of markets across the Southeast U.S. In the absolute worst case, if the insurance industry can’t pay all of the claims, then society (e.g., you and me) will be on the hook to bail it out.

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.