Aerial view of Galveston flooding after Hurricane Ike in 2008. U.S. Weather Service / Wikimedia Commons

The very first article published by Texas Climate News – on November 17, 2008 – posed a tough question in its headline: “Will Ike, other storms spur new thinking?”

This was only two months after Hurricane Ike had rammed into the Galveston Bay area. Ike obliterated homes, took some 113 lives directly or indirectly, and caused $38 billion in damage (USD 2008). Horrific as it was, this sprawling hurricane could have caused twice as much destruction in Texas had it made landfall just a bit further west or packed just a bit more storm surge.

It’s sobering to realize that in many ways, Texas is more vulnerable to hurricanes in 2024 than in 2008. Sheer growth is one reason. There are now close to 7 million residents in the state’s coastal counties, including roughly a million added in those 16 years. The vast bulk of this settlement is in the Houston area, along and not far from Galveston Bay, where Ike did its worst.

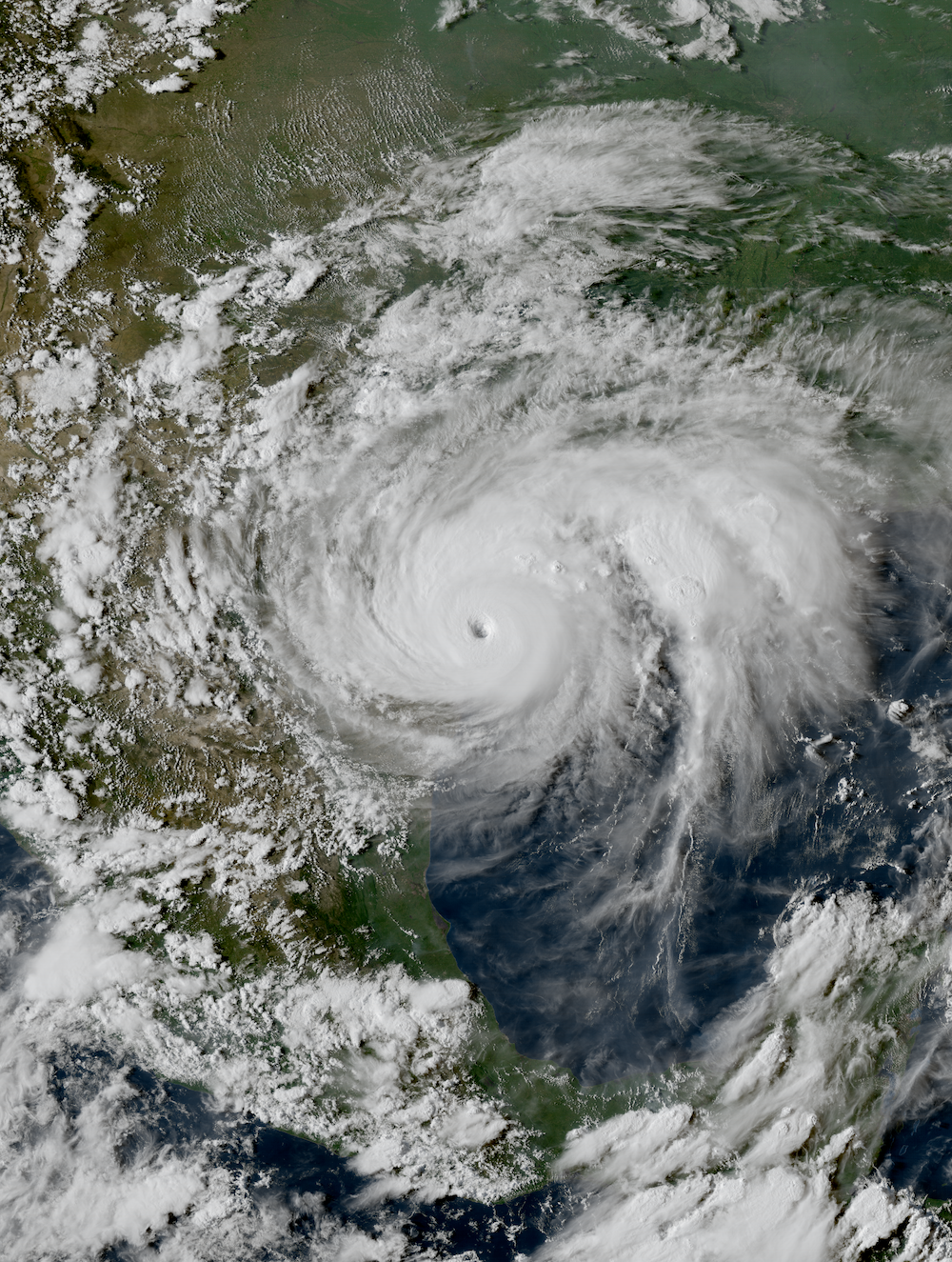

The atmosphere has flung a volley of hurricanes and tropical storms against the Texas coast since Ike. Chief among those was 2017’s Harvey, a Category 4 storm that devastated parts of the Rockport area at landfall and then slowed to a crawl, weakening and lingering for days over southeast Texas. Harvey dumped widespread rains of 30 to 40 inches and produced the largest rainfall total from any tropical cyclone in U.S. history (60.58 inches at Nederland). Along with more than 100 deaths, Harvey inflicted a mind-boggling $159 billion in damage (USD 2024), putting it just behind Katrina as the second-costliest hurricane in U.S. history.

Harvey was not just catastrophic in itself: it also served as a grim harbinger. Prior to Harvey, the nation had gone almost 12 years without a single major hurricane landfall (Category 3 or stronger). But since Harvey, six other named systems have come ashore as major U.S. hurricanes up through 2023.

Texas saw only Category 1 and tropical storm landfalls in that post-Harvey period, none of them catastrophic. Yet as demonstrated by Ike, even hurricanes below major strength can cause immense havoc.

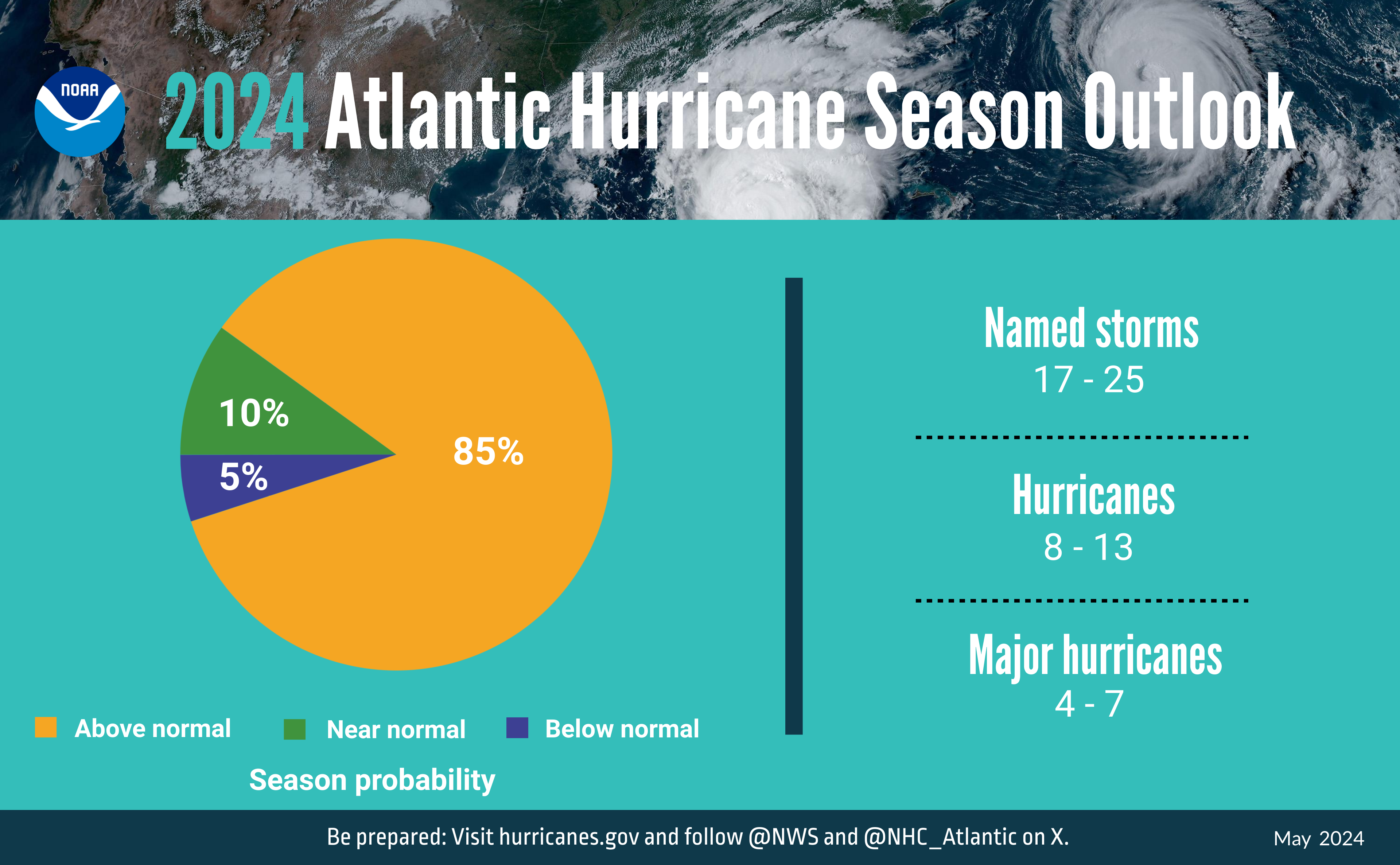

Federal forecasters last month predicted above-normal hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin (including the Gulf of Mexico) this year. Named storms are those with winds of 39 mph or higher. Hurricanes have winds of 74 mph or higher. Major hurricanes have winds of 111 mph or higher. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service

The science of increased hurricane risk in a human-warmed climate

Part of the flip from “before Harvey” to “after Harvey” can be chalked up to natural variability in hurricane steering currents. But there’s more to the story. As the climate continues to warm, ever-more-toasty waters in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean are providing more and more fuel for hurricanes. This includes four devastating ones on the Gulf Coast just east of Texas since Harvey (Michael, Laura, Ida, and Ian).

There’s also been increasing research on the ominous phenomenon of rapid intensification, in which storms can leap to fearsome strengths – sometimes in the critical 24 hours leading up to landfall, as was the case with Harvey. Multiple studies have documented this trend in the Atlantic and elsewhere. A 2024 paper found a global tripling in near-shore intensification rates from 1979-2000 to 2000-2020.

Harvey itself formed atop record-warm water in the northwest Gulf that not only facilitated the hurricane’s quick strengthening but also stoked the record-drenching rainfall that followed. “Harvey could not have produced so much rain without human-induced climate change,” concluded a 2018 analysis in the journal Earth’s Future.

There’s also been a rethinking of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, or AMO, which was envisioned as a roughly 30- to 40-year natural cycle in south-to-north heat transfer through the Atlantic. Back in 2008, the AMO was a leading hypothesis as to why Atlantic hurricanes (including those in the Gulf of Mexico) had been so frequent from the 1920s to 1960s, more sporadic from the 1970s into the 1990s, and then often raging ever since. It stood to reason that Atlantic hurricane production might again slow by the 2020s or thereabouts, blunted by the next downward turn in the AMO.

However, the scientist who had named the AMO – Michael Mann (University of Pennsylvania) – then made a rare scientific U-turn. In a 2021 paper in Science, Mann and colleagues asserted that the AMO was actually a statistical artifact, caused by postwar pollution from sun-blocking aerosols that had cooled the North Atlantic during the quiet period. With such pollutants now much less widespread, Mann sees an Atlantic bristling with hurricanes as exactly the outcome one might expect after a century-plus of greenhouse-gas-induced warming.

“Two decades ago there seemed to be both observational evidence and modeling evidence (if rather limited) for the existence of a multidecadal AMO oscillation in the climate system,” said Mann in a 2021 blog post. He added that he and colleagues now have been “led inescapably to the conclusion that the AMO…doesn’t actually exist.”

Also mulling the topic is Phil Klotzbach, who now leads seasonal hurricane prediction at Colorado State University. The CSU group had long used the AMO as a forecast tool, but lately it’s not been behaving as expected. “The AMO is tricky right now,” said Klotzbach in an email. For one thing, colder-than-average waters in the far North Atlantic aren’t linked with hurricane-favorable summer conditions in the tropics as reliably as they once were.

Also in the mix is an unexpected and somewhat mysterious trend toward La Niña rather than El Niño in the last several decades. According to Klotzbach, this also counteracts the presumed AMO influence and works in favor of Atlantic hurricanes. If La Niña were to remain more frequent than El Niño for decades more, it could substantially hike the risk of landfalling hurricanes in Texas.

“There is certainly natural multidecadal variability in the North Atlantic, but there is an anthropogenic component influencing things as well,” Klotzbach said.

Hurricane Harvey as it reached Texas at peak intensity on Aug. 25, 2017. Lingering along the state’s coastline, the hurricane caused catastrophic flooding in Houston and neighboring areas and claimed more than 100 lives. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration / Wikimedia Commons

How Texas is adapting and faring as hurricanes step up their game

As for the broader picture of how hurricane-relevant policy has evolved in Texas, consider several queries posed high up in that 2008 TCN story, reproduced here in italics.

Should Texans adopt more policies and practices to reduce the state’s considerable production of carbon dioxide, the principal greenhouse gas that scientists say is warming the atmosphere? Texas ranks No. 1 among the states for CO2 emissions.

As of the most recent year of data (2021), that was still true – and by a long shot. The total Texas CO2 emissions of 663.5 million metric tons was more than twice that of the next runner-up state, California, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Wind and solar development have boomed in Texas – especially wind power, largely due to a 1999 act deregulating the electric power system. But state lawmakers have consistently refused since Ike and later climate disasters to pass (or, typically, even consider) bills filed to reduce greenhouse emissions or study the impact of climate change on Texas.

After the Legislature last met, in 2023, a Texas Tribune headline summed up the session’s record on energy and climate: “Fossil fuels got a boost from lawmakers aiming to fix Texas’ grid, while renewable energy escaped stricter regulations.”

Is it wise to encourage or even permit building (or rebuilding, as the case may be) in some hazard-prone locations near the coast? Thousands of homes were flooded by Ike.

Rebuilding and resilience, not retreat, was Galveston’s post-Ike theme, just as it was after a catastrophic 1900 hurricane. “Dozens of projects,” ranging from better-draining roads to a new, backup water line, were installed or planned to help withstand future storms’ impacts, the Houston Chronicle reported in 2018, the 10th anniversary of Ike’s devastating blow to the island city, including major flooding.

New building codes and standards, including requirements to build above flood elevation, meant “we’re definitely improving our ability to weather another storm,” a city official told the Chronicle. (Houston, after Hurricane Harvey’s catastrophic flooding in 2017, required elevated construction in floodplains. Also post-Harvey, voters in Harris County, where Houston is located, approved a $2.5 billion flood mitigation program.)

Galveston’s slowly growing population was not back to it’s pre-Ike level of 57,000 residents in the Census Bureau’s latest estimate in 2013. But new construction continues. A pair of multi-million-dollar projects were announced in January amid “the island’s white-hot tourism industry,” according to a news report. Some, at least, were undeterred by Ike’s legacy and the online insurance broker Assurance’s decision to put Galveston at the top of its 2023 list of the riskiest 75 U.S. beach towns based on hurricane frequency and the value, percentage, and populations of at-risk homes.

Related questions involve the extent to which all Texans should share the financial risk of coastal residents through the Texas Windstorm Insurance Pool.

The Texas Windstorm Insurance Association, the state-mandated insurer of last resort, now serves some 231,000 property owners. Private home insurance rates jumped in Texas by 23.3% in 2023 – the highest rate of any U.S. state, and double the U.S. average, according to S&P Global. Yet during most of the past few years, the association board has rejected any rate increase for its own residential and commercial properties. The result: a growing gap between resources and risk. “Failing to charge adequate premiums means a big storm could bankrupt TWIA and leave the Legislature scrambling to cover unpaid claims with taxpayer money,” warned Houston Chronicle columnist Chris Tomlinson in 2023.

Should Texas require utility companies to take protective measures for their electricity-distribution systems, as Florida did, to “harden” them against hurricane damage?

In 2009, the year after Ike deprived millions of Houston-area residents of electricity, a task force assembled by Houston’s mayor recommended against burial of power lines – an often discussed “hardening” measure. Burying the lines would cost an unacceptably expensive $35 billion, the group declared. Alternatively, the region’s major electricity provider installed more “high-tech power poles” to reroute power more quickly in outages and removed more trees that could fall across power lines in a storm. But utility officials admitted in 2013 that such measures would help speed up recovery after major storms and not greatly reduce the number of people without electricity.

The question of how to protect utility supplies from extreme weather took on additional, unexpected gravity during the brutal, deadly Texas cold wave of February 2021, part of the nation’s costliest winter storm on record. The disaster took almost half of the state’s electrical generation offline and nearly triggered a catastrophic failure. Meanwhile, research at the University of Texas’ Energy Institute and elsewhere is confirming the immense value of bolstering the grid against hurricanes. A 2024 study in Nature Energy examined seven tropical cyclones affecting the Texas power grid from 2003 to 2020 and found that hardening just 1% of the state’s electrical grid lines could make the worst type of outage from 5 to 20 times less likely.

Whither the Ike Dike?

Perhaps the most vexing yet most crucial single policy choice that still looms for Texans on hurricane protection is one pushed to the fore by Ike in 2008: Should a seawall and floodgate initiative be built to protect Galveston and the Galveston Bay area? And if so, how?

The U.S. Corps of Engineers (USACE) is well into a decades-long effort to plan, approve, and eventually build a coastal barrier system commonly known as the “Ike Dike,” which would likely be the largest civil engineering project in U.S. history. Importantly, the anticipated 20-year design and construction process means that the barrier would not be in place until 2045 at the earliest. That leaves plenty more time for more hurricanes to wreak havoc, and for sea level to keep rising – a related process, also aggravated by climate change, that increases hurricanes’ storm-surge impacts.

The coastal barrier, as laid out in a five-year, $20-million feasibility study released in 2021 by USACE and the Texas General Land Office, could cost at least $57 billion once inflation is factored in, as reported by the Texas Tribune. After years of study and public discussion, the project was finally authorized by Congress in 2022 but has received neither federal construction funding nor the roughly one-third of the cost to be borne by Texans. The U.S. House Appropriations Committee rejected a $100 million funding request for the Ike Dike last year, but the Corps of Engineers did allocate $500,000 in May for engineering and design work on part of the project.

Gates at the entrance to Galveston Bay from the Gulf of Mexico would be a key part of the proposed Ike Dike project. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Texas General Land Office

Researchers at Texas A&M Galveston have pushed for a more expansive Ike Dike concept, going well beyond the USACE proposal. They argue that the Gulf-facing coastline needs a full land barrier with sand dunes surrounding a solid core, rather than the dual set of erodible sand dunes proposed by USACE. They also call for a gate system at San Luis Pass to prevent back-door intrusion of storm surge from the west into Galveston Bay.

In an online response, the team sharply critiqued the USACE proposal: “The concept of a strong regional-scale coastal spine as a first line of defense to reduce flood damage has been abandoned.”

Meanwhile, the multi-institution SPEED Center (Severe Storm Prediction, Education, & Evacuation from Disasters), based at Rice University, has put forth a Galveston Bay Park Plan. It calls for a north-south string of new islands in the western bay that would protect much of the immediate coast while supporting marine ecology and recreation. Houston, Harris County, and the Port of Houston Authority teamed with Rice in 2023 to fund a $1 million assessment of the project.

As envisioned, Galveston Bay Park wouldn’t supplant the Texas Coastal Barrier but rather precede and complement it. “Over time, as the federal procurement process evolves, the Coastal Barrier can be completed to provide broader and more comprehensive protection for the entire bay system,” said a 2024 update from SSPEED. “But in the short-term, the Park Plan can provide significant reduction in surge vulnerability at a very high rate of return on the investment and can also propel forward our next required navigation improvements for the Ship Channel.”

The SSPEED update closed with an observation that’s as basic yet as pertinent to Texans and tropical cyclones in 2024 as it would have been in 2008:

“Our vulnerability to a major hurricane is very real.”

Bob Henson, a contributing editor of Texas Climate News, is a journalist and meteorologist. TCN founding editor Bill Dawson contributed to this article.