Stagnant water sits below the dry spillway of Falcon Dam in Starr County on Aug. 18, 2022. Michael Gonzalez / The Texas Tribune

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Two consecutive summers of brutal heat and drought have left some parts of Texas with notably low water supplies going into 2024.

A wet year or a well-placed hurricane could quickly pull these regions back from the brink. But winter rains have disappointed so far. Monday’s downpours are the first in weeks for parts of the state and they won’t hit the watersheds that need them most.

Looking ahead, forecasters increasingly expect another scorching summer here this year.

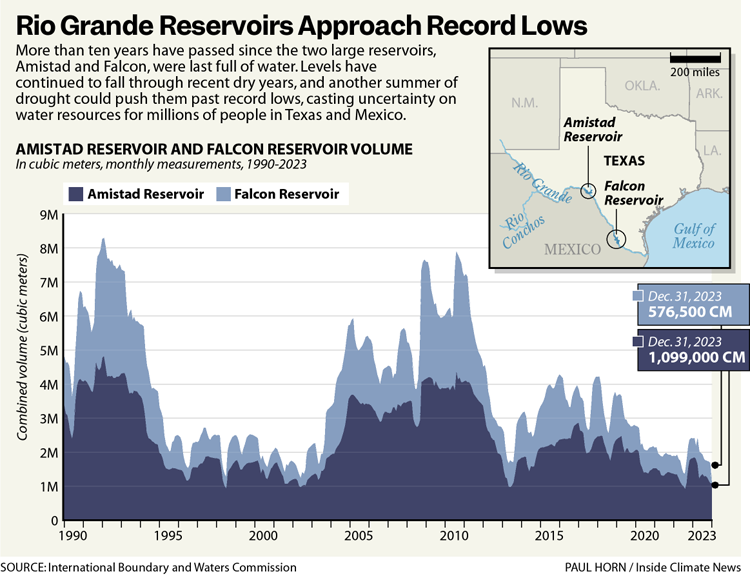

That’s bad news for places like far South Texas, where big reservoirs on the Lower Rio Grande fell from 33 percent to 23 percent full over the last 12 months. A repeat of similar conditions would leave the reservoirs far lower than they’ve ever been, triggering an emergency response and an international crisis.

“Pretty scary times,” said Jim Darling, president of the Rio Grande Regional Water Authority and former mayor of the city of McAllen. “We’ll see what happens.”

Worries stretch beyond the Rio Grande. In Corpus Christi, on the South Texas coast, authorities last month stopped releasing water aimed at maintaining minimum viable ecology in the coastal wetlands, even as oil refineries and chemical plants remain exempt from water use restrictions during drought.

Also last month, in the sprawling suburbs of Central Texas, between Austin and San Antonio, one groundwater district declared stage 4 drought for the first time in its 36-year history.

Texans don’t usually talk about drought in the winter. Damp soil and green grass may conceal the impending predicament today, but water planners in regions with low reserves nervously await what summer may bring.

“Signs are not favorable,” said Greg Waller, a coordinating hydrologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Fort Worth. “Expect warmer and drier, again.”

Winter and spring rains offer the best hope for relief, he said, but weather patterns so far haven’t produced the sustained downpours needed to refill reservoirs.

Drought conditions in 2022 and 2023 struck with markedly acute severity. Last year was the hottest on record for Texas—and the Earth, according to NOAA—after a global heatwave shattered temperature records around the world.

These patterns, Waller said, are consistent with scientific understanding of climate change caused by carbon emissions.

“Climate change means the extremes are going to get more extreme,” he said. “The heat waves are going to get more heat. The droughts are going to get droughty-er and the floods are going to get floody-er.”

Texas rainfall typically peaks in May. If relief doesn’t come by then, some places will need to start bracing for impact.

A mural of ocean life at the Citgo refinery on the Corpus Christi Ship Channel. Dylan Baddour / Inside Climate News

Corpus Christi: Wetlands and refineries

Corpus Christi, with 421,000 people in its two-county metro area, sits where the Gulf Coast marshes meet the semi-arid South Texas plains. The region’s combined reservoirs dropped from 53.7 percent full in 2022 to 43.6 percent in 2023 to 30.5 percent this month.

The city announced in December that it would no longer release water from its reservoir system to support basic ecology in coastal bays and estuaries.

“Due to the ongoing drought in our water supply,” wrote a city spokesperson in a statement. “NO water is being released from Lake Corpus Christi to the Bays and Estuaries.”

Wherever Texas rivers join the sea, these once-vast wetlands host critical reproductive cycles of many aquatic species, and they depend on freshwater inflows for their characteristically half-salty, nutrient-rich systems. When water supply gets tight, the bays and estuaries typically are first to see their allocations revoked while cities keep dam gates closed.

These ecosystems, which once benefited from all the water from the formerly undammed rivers of Texas, have adapted to natural droughts. Dry years severely decrease the amount of species reproduction, but when wet weather returns, the system can usually recover within a year, according to Paul Montagna, endowed chair of Hydroecology at Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies in Corpus Christi.

“However, if a system is permanently impaired it is also possible that recovery will not reach former levels,” Montagna said.

Studies suggest that systems around Corpus Christi may already be “permanently impaired,” Montagna said, largely due to a sustained lack of fresh water.

Similar problems span the lower Texas coast. The Rio Grande hasn’t flowed consistently into the Gulf of Mexico since the early 2000s. On the Colorado River, which runs through Austin, authorities have kept water releases to the coastal wetlands at a bare minimum in recent years. Jennifer Walker, director of the National Wildlife Foundation’s Texas Coast and Water Program, called it “critical life support.”

“Water to meet environmental needs is frequently the first to be negotiated away,” Walker said. “Our bays and estuaries are a hugely important part of Texas and they’re not something that would be easy to go back and fix.”

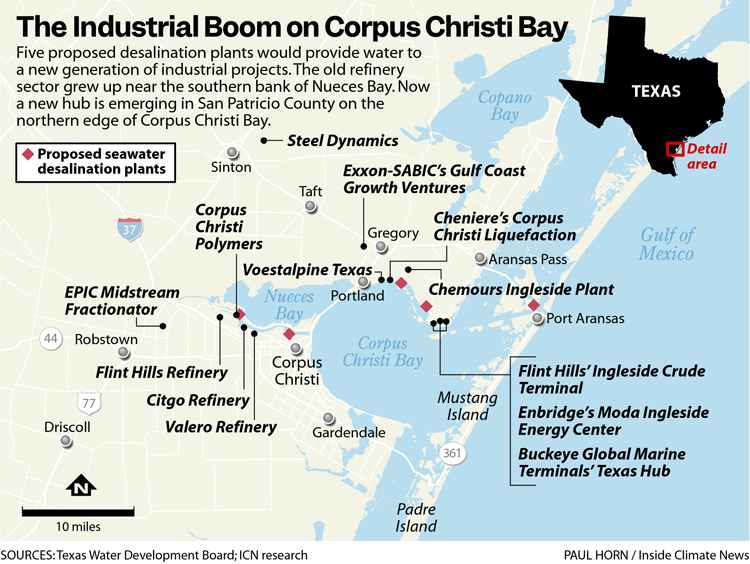

In Corpus Christi, a major refining and export hub for Texas shale oil and gas, city authorities have imposed water use restrictions on residents, with more to come if reservoir levels fall below 30 percent. But the region’s largest industrial water consumers operate unabated, thanks to a purchasable exemption from drought restrictions for industrial users—$0.25 per 1,000 gallons—passed by the city council in 2018.

That includes users like ExxonMobil’s massive new plastics plant, which is authorized to use up to 25 million gallons of water per day—a quarter of the regional summertime water demand.

“Industry can continue full bore through all of these drought stages and the estuary gets cut off early,” said a water resource consultant from Corpus Christi who requested anonymity to preserve his business relationship with the city. “I think it’s a looming disaster. They are still trying to recruit all these water-intensive industries along the coast.”

Proceeds from the exemption program were supposed to fund development of seawater desalination plants that would expand the regional water supply and meet demands of a booming industrial buildout. The first plant was initially planned to begin operations early last year, but it remains mired in challenges and years away from breaking ground. Meanwhile, the industrial buildout continues.

Central Texas: People and grass

Two hundred miles inland, the five-county region surrounding Austin, Texas’ high-tech capital city, has grown faster than any U.S. metro area for 12 straight years. Its water supplies haven’t.

In 2022, less water flowed into City of Austin reservoirs than ever before, city staff said at a public water task force meeting on Tuesday. Last year was only slightly better. The largest reservoir serving Austin, Lake Travis, fell from about 80 percent full in January 2022 to 38 percent full at the start of this year.

Even in another extreme drought year, Austin can avoid heightened water use restrictions, which take effect when reservoirs fall below 30 percent full, until at least July, according to a water supply outlook presented at the meeting. But the outlook stopped short of August and September, the region’s hottest and (recently) driest months.

“It’s not looking good,” said Robert Mace, director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University and a member of the water task force.

Even if levels fall below 30 percent, water users in Austin will face only minor restrictions, focused mostly on car washing and lawn irrigation. During the summer in Texas, when water consumption can double or triple over wintertime use, major cities spray most of their treated drinking water onto grass.

The problem worsens as more land converts to suburban subdivisions amid a homebuilding boom, said Todd Votteler, a water dispute consultant and editor of the Texas Water Journal, a peer-reviewed journal focused on water management and research. Texas gained more residents and built more homes than any state in recent years.

“One of the challenges is the idea for home builders and the real estate industry that all these new houses need to have beautiful green lawns,” said Votteler, who has worked at groundwater and river authorities in Central Texas since 1994. “People moving here from some place else have not lived in a region with a limited water supply.”

Around the city of Austin, a patchwork of authorities manages various aquifers and reservoirs. Last month, the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Groundwater Conservation District declared stage four drought restrictions for the first time in its 36-year history. That required the oldest communities and major companies in the district to reduce water use by 40 percent, while 16 newer permit holders were cut off entirely.

The district’s customers include the small city of Kyle, the third-fastest growing U.S. city in 2022, plus dozens of small water companies and utility districts.

“We’ve been concerned for years. We’ve been in one stage of drought or another for well over a year and a half now,” said Tim Loftus, general manager of the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Groundwater Conservation District. “We just really need rain.”

Loftus said his customers have “risen to the occasion” and complied with cuts. Another district hasn’t been as lucky.

Aqua Texas, an investor-owned water utility, pumped almost twice as much groundwater as its permit allowed in 2022, according to officials with the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District. Photographed on Thursday, August 10, 2023 outside Wimberley, Texas. Dylan Baddour / Inside Climate News

The neighboring Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District has fought for two years with a local subsidiary of a national investor-owned water supply company over violations of permit pumping limits, even as severe drought conditions have continued to deepen.

The company, Aqua Texas, has taken almost twice its permitted allotment for two consecutive years and has declined to abide by drought restrictions, according to Charlie Flatten, general manager of the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District. This month, Aqua sued the conservation district in federal court. Its legal brief didn’t address whether Aqua had overpumped, but accused the groundwater district of violating due process and of “unequal application of its penalty policy.” It added that “Aqua Texas has voluntarily spent millions of dollars in water conservation.” The groundwater district, in legal documents, has denied Aqua’s allegations.

“We’re already seeing wells drying up, not just in specific sections but across the district,” Flatten said. “As we continue to use water and there continues to be no recharge, more and more wells will be affected.”

Another major nearby water source, the Canyon Lake reservoir, started last year 80 percent full, surpassed its record low of 68 percent in August and is 60 percent full today.

A bridge in Zapata, Texas, crosses a dry bed on the Falcon Reservoir. Dylan Baddour / Inside Climate News

The Lower Rio Grande: Texas and Mexico

The biggest water problems in Texas lie along its southern border, where some 6 million people in two countries depend on the dwindling Lower Rio Grande system.

At the river’s end, amid the irrigated fields of the fertile Rio Grande Valley, farmers have lost crops midseason in recent years due to water shortages. This year, many won’t plant at all, worried they will lose the investment to another summer drought, said Darling, the Rio Grande Regional Water Authority president.

That creates a spiraling conundrum for the flourishing cities of the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, home to more than a million people, he said. The once-prosperous agricultural sector historically accounts for more than 80 percent of water demand here. Without its vast volumes flowing for irrigation, the region’s network of canals would almost dry up. Cities would lose more than half their water supply to evaporation and soil absorption along its 70-mile journey from the nearest reservoir.

There are two possible temporary remedies to this problem, Darling said.

One is the weather. The only other time the Rio Grande reservoirs fell as low as they have today, around 2000, a hurricane soon hit and refilled them almost entirely. A Pacific storm could also bring relief to the bulk of the Rio Grande watershed, which covers the mountains of northwestern Mexico.

Another is international politics. Because most of the water used by Texas farmers on the Lower Rio Grande originates as rainfall in Northern Mexico, a binational treaty governs water sharing between the countries.

Northern Mexico has experienced its own water crises lately, including a deadly riot at a reservoir dam in 2020 and months of water rationing in 2022 in one of the country’s largest cities. So, it’s been reluctant to release water for Texas farmers, contributing to low levels in the downstream reservoirs.

Since 2020, Mexico has fallen sharply behind on its schedule of water releases to Texas under the treaty, which was ratified in 1944. It has until the end of 2025 before it faces delinquency. But the Rio Grande Valley of Texas might not have another two years to wait, Darling said.

The political situation is managed primarily by the International Boundary and Water Commission, a small agency operated by the U.S. and Mexico.

“We are negotiating an agreement with Mexico intended to improve the predictability and reliability of Rio Grande water deliveries,” said an agency spokesperson, Frank Fisher. “We hope this agreement will provide tools that will help users affected by supply shortages.”

North of the border, Fisher said, water restrictions will be managed by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

A TCEQ spokesperson, Victoria Cann, said the agency “has warned users about declining storage and encouraged users to plan for water shortages.”

“TCEQ continues to advocate for water users on the Rio Grande by communicating to IBWC the need for Mexico to deliver on their water obligations under the 1944 Water Treaty,” Cann said.

Dylan Baddour covers the energy sector and environmental justice in Texas for Inside Climate News.