Jan. 16, 2024 – First snow of the year at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Darryl Vaca / U.S. Army via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Over the past few days, extremely cold Arctic air and severe winter weather have swept southward into much of the U.S., breaking daily low temperature records from Montana to Texas. Tens of millions of people have been affected by dangerously cold temperatures, and heavy lake-effect snow and snow squalls have had severe effects across the Great Lakes and Northeast regions.

These severe cold events occur when the polar jet stream – the familiar jet stream of winter that runs along the boundary between Arctic and more temperate air – dips deeply southward, bringing the cold Arctic air to regions that don’t often experience it.

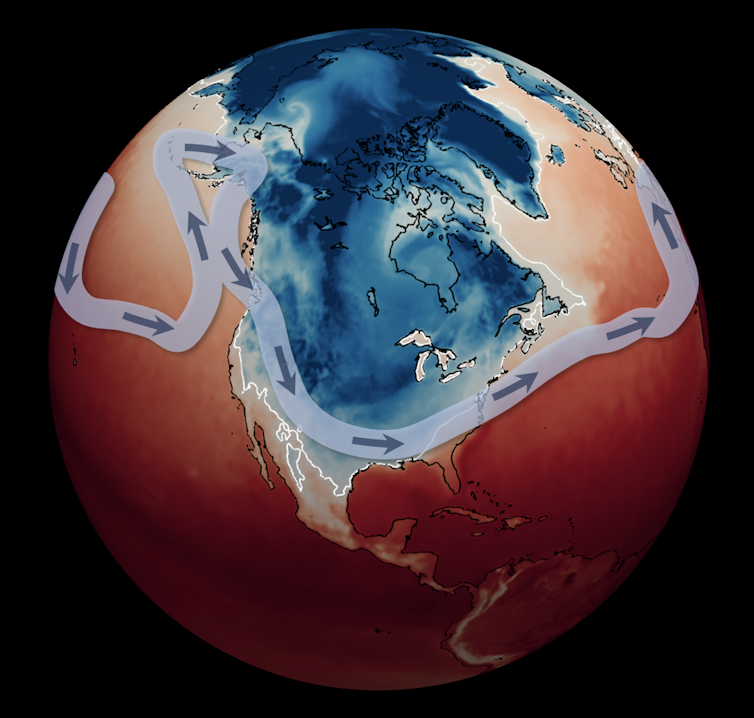

Surface temperatures at 7 a.m. EST on Jan. 16, 2024. Temperatures below freezing are in blue; those above freezing are in red. The jet stream is indicated by the light blue line with arrows. Mathew Barlow/UMass Lowell CC BY

An interesting aspect of these events is that they often occur in association with changes to another river of air even higher above the jet stream: the stratospheric polar vortex, a great stream of air moving around the North Pole in the middle of the stratosphere.

When this stratospheric vortex becomes disrupted or stretched, it can distort the jet stream as well, pushing it southward in some areas and causing cold air outbreaks.

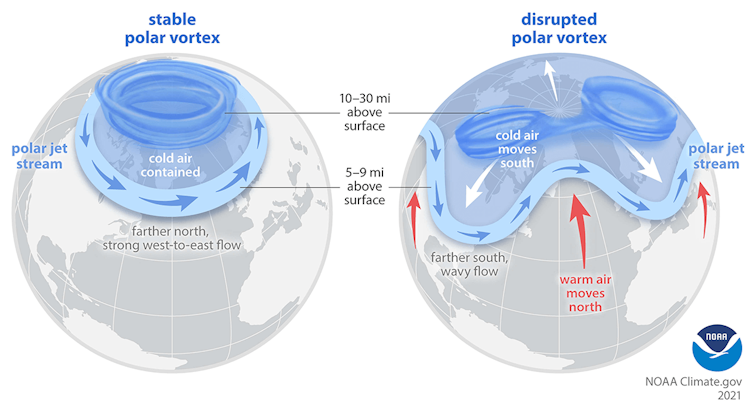

The Arctic polar vortex is a strong band of winds in the stratosphere, 10-30 miles above the surface. When this band of winds, normally ringing the North Pole, weakens, it can split. The polar jet stream can mirror this upheaval, becoming weaker or wavy. At the surface, cold air is pushed southward in some locations. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The current Arctic cold blast fits into this pattern, with the polar vortex stretched so far over the U.S. in the lower stratosphere that it has nearly split in two. There are multiple causes that may have led to this stretching, but it is likely related to high-latitude weather in the prior two weeks.

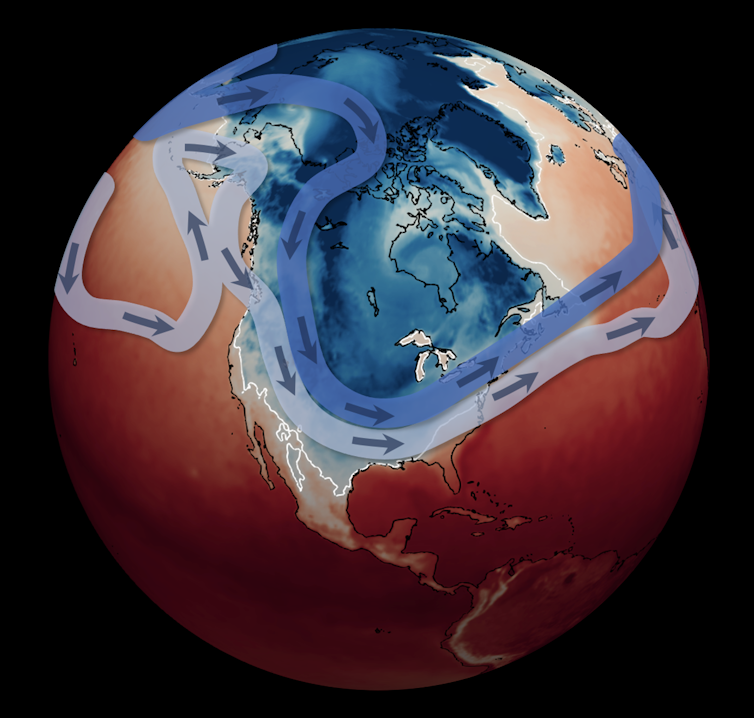

Surface temperatures and the jet stream at 7 a.m. EST on Jan. 16, 2024, with the stratospheric polar vortex also shown as the dark blue line. Mathew Barlow/UMass Lowell, CCBY

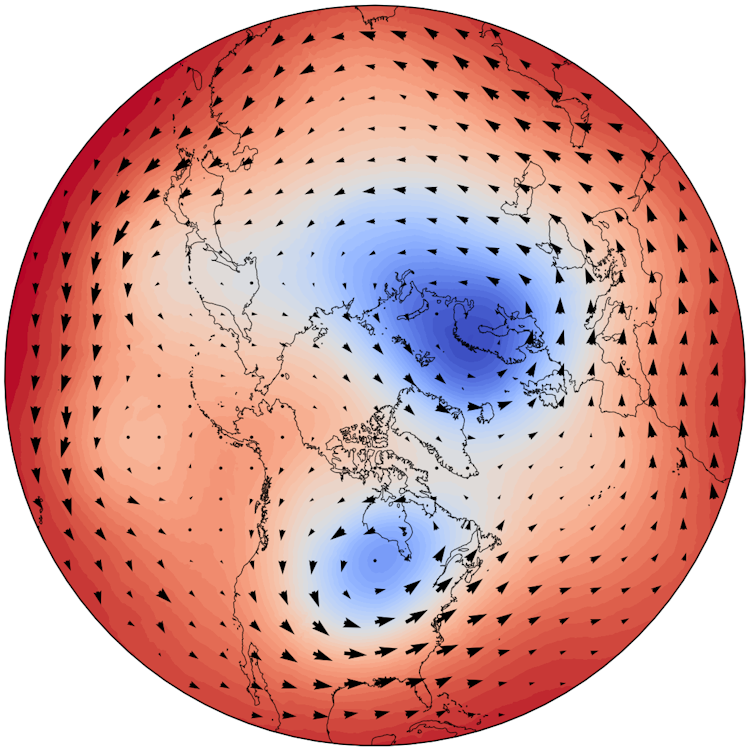

A polar view of the winds in the lower stratosphere at 7 a.m. EST on Jan. 16, 2024. The winds shown are approximately 10 miles above the surface, in the lower stratosphere. Mathew Barlow/UMass Lowell CCBY

No, cold doesn’t contradict global warming

After Earth just experienced its hottest year on record, it may seem surprising to set so many cold records. But does this cold snap contradict human-caused global warming? As an atmospheric and climate scientist, I can tell you, absolutely and unequivocally, it does not.

No single weather event can prove or disprove global warming. Many studies have shown that the number of extreme cold events is clearly decreasing with global warming, as predicted and understood from physical reasoning.

Whether global warming may, contrary to expectations, be playing some supporting role in the intensity of these events is an open question. Some research suggests it does.

The February 2021 cold wave that severely disrupted the Texas electric grid was also associated with a stretched stratospheric polar vortex. My colleagues and I have provided evidence suggesting that Arctic changes associated with global warming have increased the likelihood of such vortex disruptions. The effects of the enhanced high latitude warming known as Arctic amplification on regional snow cover and sea ice may enhance the weather patterns that, in turn, result in a stretched polar vortex.

More recently, we have shown that for large areas of the U.S., Europe and Northeast Asia, while the number of these severe cold events is clearly decreasing – as expected with global warming – it does not appear that their intensity is correspondingly decreasing, despite the rapid warming in their Arctic source regions.

So, while the world can expect fewer of these severe cold events in the future, many regions need to remain prepared for exceptional cold when it does occur. A better understanding of the pathways of influence between Arctic surface conditions, the stratospheric polar vortex and mid-latitude winter weather would improve our ability to anticipate these events and their severity.

Mathew Barlow is a professor of climate science at UMass Lowell. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.