A satellite image showing the wildfire that devastated the historic city of Lahaina on the west coast of the Hawaiian island of Maui in August. Another large fire is shown on the right side of this image, northeast of the city of Kihei. Public domain photo by NASA Earth Observatory via Wikimedia Commons

TCN Digest articles present our summary selections of recent news with a common theme or close connections, along with explanatory context and links for further reading.

When U.S. climate scientists announced last week that last month was Earth’s warmest September in records dating to the middle of the 19th century, they were formally certifying the continuation of an astonishing run of extreme heat. The previous three months – “meteorological summer” in scientific terminology — had already entered the record books as the warmest June, July and August.

“Not only was it the warmest September on record,” said Sarah Kapnick, chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “it was far and away the most atypically warm month of any in NOAA’s 174 years of climate keeping. To put it another way, September 2023 was warmer than the average July from 2001-2010.”

Last month’s persistence of 2023’s Big Heat and associated climate extremes – particularly but not exclusively in the Northern Hemisphere – also meant this year is almost certain to end as the warmest on record, NOAA said.

As much as many Texans and others around the world who endured this year’s brutal weather might want to forget about it as fall-like conditions arrive, NOAA’s announcement about September’s record global warmth was a reminder that more of the same is in store:

Many scientists expect 2024 to bring more such scorching conditions, joining 2023 as a harbinger of even greater weather-related challenges beyond next year as fossil-fueled climate change progresses and possibly accelerates.

“A truly staggering margin”

Scientists and science journalists sometimes struggled to convey just how amazing Summer 2023’s scorching, enervating, record-setting, life-threatening temperatures were – even in the context of a demonstrably warming atmosphere.

“The past four months of 2023 have shattered all prior records by a truly staggering margin,” climate scientist Zeke Hausfather of the Berkeley Earth data project wrote on the Climate Brink blog that he co-authors with Texas A&M atmospheric sciences professor Andrew Dessler.

Several days later on X (formerly Twitter), Hausfather decided to depart from his characteristically technical explanatory style in an effort to do verbal justice to what he saw in September’s global temperature record: “This month was, in my professional opinion as a climate scientist, absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.”

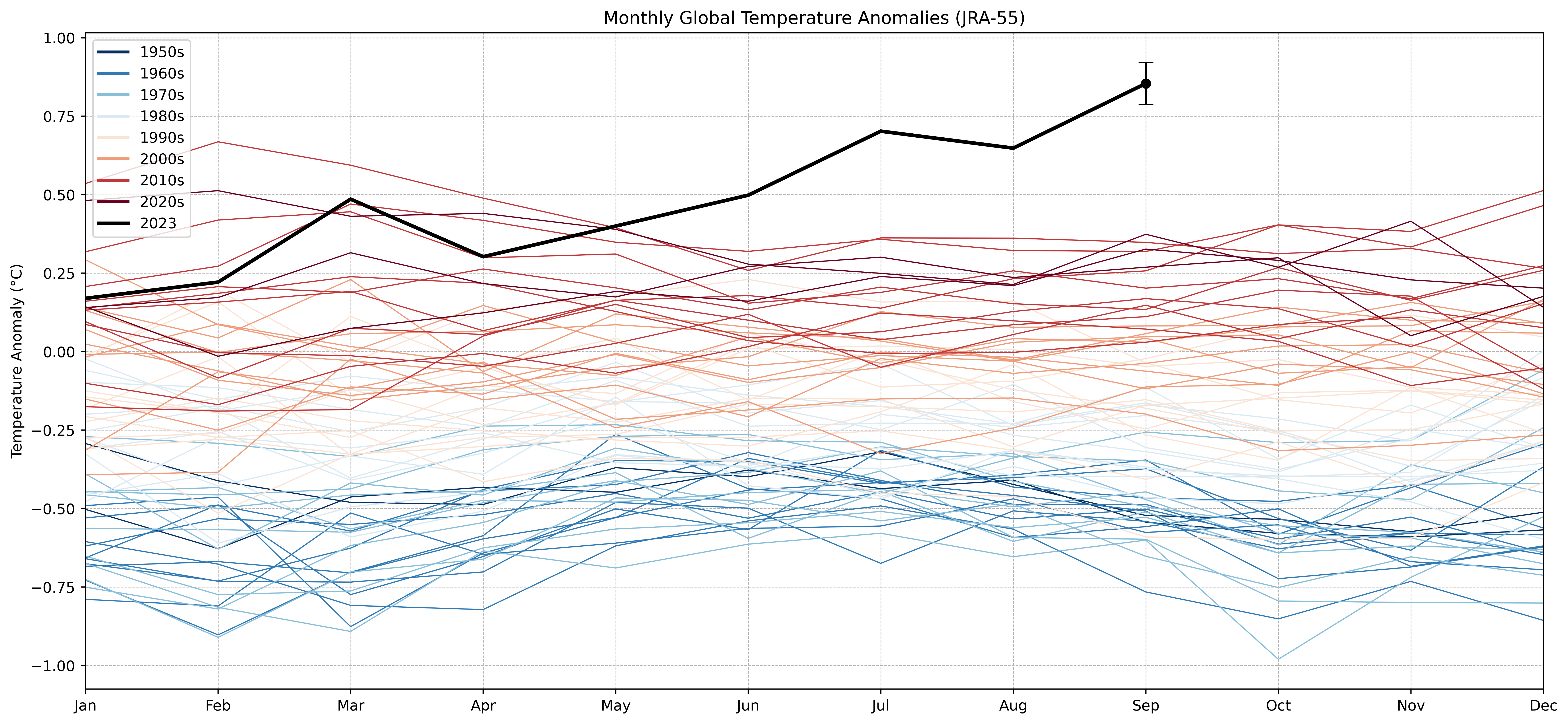

A chart from Zeke Hausfather’s blog post, cited above, that shows how global monthly temperatures compared to a 1991-2020 baseline. The average for 2023, including Hausfather’s estimate for September, is shown by the black line.

Rachel Dobbs, news editor of the U.K.’s newsmagazine The Economist, wrote near the end of July that its journalists were sensing a realization among their audiences that this summer’s extreme heat and other climate phenomena were something shocking:

In recent weeks, public attention [to climate change] has proved much easier to capture than usual. Widespread, record-breaking heatwaves in America and Europe made headlines in the Western press, as they would be expected to. But so too did astonishingly high temperatures in China, the Middle East and North Africa; torrential rains in India and South Korea and on America’s east coast; a destructive storm sweeping across the Balkans; wildfires raging on Greek islands; and freakishly warm sea-surface temperatures. The difference this time is that all these events, in all their separate locations, are suddenly happening more or less simultaneously.

Extreme heat and other events associated with global warming continued on multiple continents after Dobbs wrote. Here are a couple of thorough journalistic overviews that can help understand their scope and severity:

Politico’s E&E News ominously headlined its article “The summer from hell was just a warning.” In it, veteran climate science reporter Chelsea Harvey offered a comprehensive catalog of the summer’s most notable weather extremes and worst climate disasters in the context of scientists’ perspective about what they mean and foretell.

It’s been a summer of norm-shattering extremes — with temperatures beyond human memory, catastrophic floods from Beijing to Vermont, choking wildfires and climate records tumbling on every continent.

Welcome to the rest of our lives.

The Guardian’s “visual timeline,” with ample photos, maps and charts, summarized June-through-September’s “series of extreme weather events exacerbated by climate breakdown caused death and destruction across the globe.”

The U.K. newspaper’s chronology stretched from “unusually intense” rains in Haiti in early June, which killed 42 and destroyed more than 10,000 homes, to the “world’s deadliest weather event of the year” in Libya in September, in which more than 11,000 died in flooding:

“In a single day [in the Libya catastrophe], Storm Daniel unleashed 200 times as much rain as usually falls on the city in the entire month of September. Human-induced climate change made this up to 50 times more likely.”

Texas and nearby

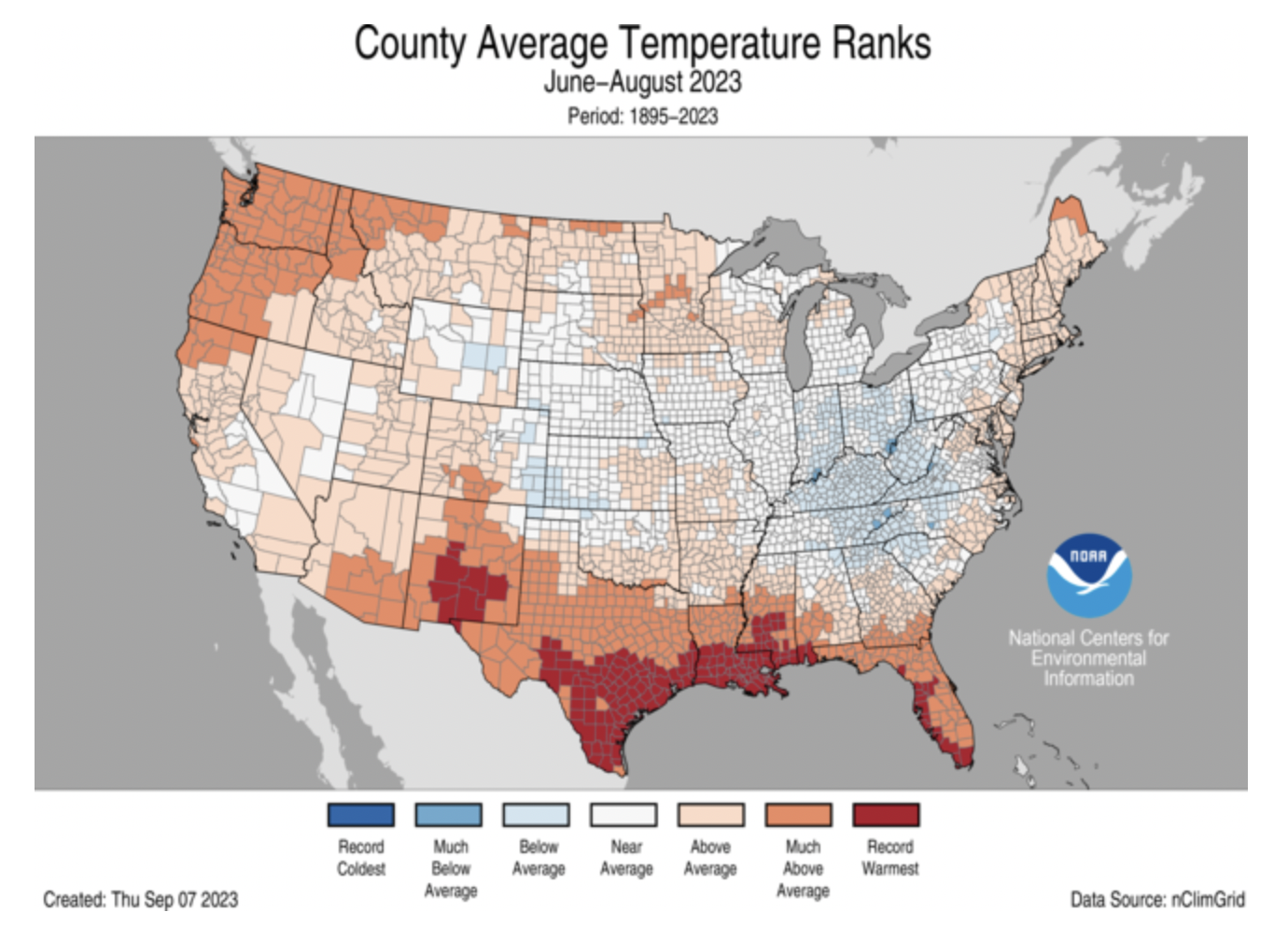

With many locations’ daily high temperatures stuck in the 100s for weeks and weeks, Texas as a whole had its second-hottest meteorological summer on record. About a third of the state experienced its hottest June-July-August season in long-running “heat dome” conditions, while most of the rest was in the “much above average” category, according to NOAA.

The average temperature in Texas for those three months was 85.3 F, slightly behind the 86.8-degree average of the state’s hottest summer on record – 2011, when a record-setting drought also occurred.

This map published by NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Information shows that most counties in South Texas and southern Louisiana experienced their hottest summers on record this year.

Emily Borchard, meteorologist for Spectrum News in Austin and San Antonio, appraised Texas’ summer heat in a number of Texas cities, especially focusing on South Texas locations, in a Sept. 8 article.

“Some notable records from this summer include the most 105-degrees or hotter days and consecutive days of triple-digit heat for several cities,” she wrote. Austin, for example, had 30 days at 105 degrees or hotter from June-August, its largest number on record, as well as the most 100-degree days for the city – 45.

Reviewing NOAA’s national climate summary for June-July-August for Yale Climate Connections, the meteorologist and journalist Bob Henson (a TCN contributing editor), placed Texas’ August temperatures – the state’s second-hottest on record – in a regional and national perspective:

The heat last month was particularly brutal across the Gulf Coast states from Texas to Florida. Persistent drought and light winds allowed the coastal plains and the adjacent Gulf waters to roast to unprecedented levels, in many cases topping record August averages by 2 degrees Fahrenheit or more. Three states saw their hottest August on record — Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi — and it was a top-10 hottest August in eight other states, extending to Oregon and Washington, as shown in Figure 2. No state had an August that was significantly cooler than average. Averaged across the contiguous 48 U.S. states, summer 2023 was the ninth-hottest in 129 years of record-keeping, according to NOAA.

Climate change made Texas’ scorching heat in July far more likely, as it did in many other places, according to an analysis of that month’s temperatures in 200 countries and 4,700 cities by Climate Central, an independent research organization. July was the world’s hottest month on record.

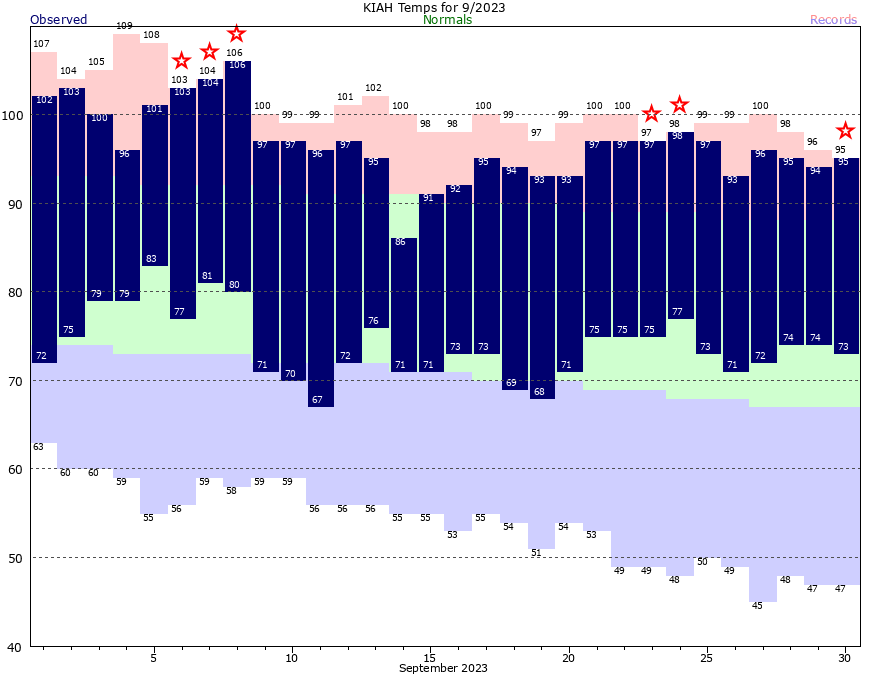

Extreme heat continued in September in Houston. The red stars on this National Weather Service chart mark days when the high temperature tied the previous record or set a new record. The green band shows the city’s “normal” temperature range.

Coastal Texas was one of the locations in the analysis with “very intense temperatures and a strong climate signal,” Andrew Pershing, Climate Central’s vice president of science, said in a media briefing on Aug. 1.

Houston, for example, recorded an average level of 3.5 in July on the organization’s Climate Shift Index, a tool for calculating how much daily temperatures are attributable to manmade climate change. An index level of 3 means climate change meant a day’s temperature was at least three times more likely in that place.

The “summer from hell” that stuck around

This year’s deadly heatwaves dated back to April 23, well before summer’s official start. The year’s extreme heat has also lingered in September and October in many places, reaching record-setting levels across Europe, Asia and North America and accompanying other events and conditions that scientists say are spinning off from a warming climate.

The Associated Press reported on Sept. 18, for instance, that Louisiana, “typically one of the wettest states in the country, is on fire.” The AP noted that the state’s “unprecedented” wildfire season was continuing in force at that time, “stoked by record-breaking heat, drought and plentiful dry vegetation.”

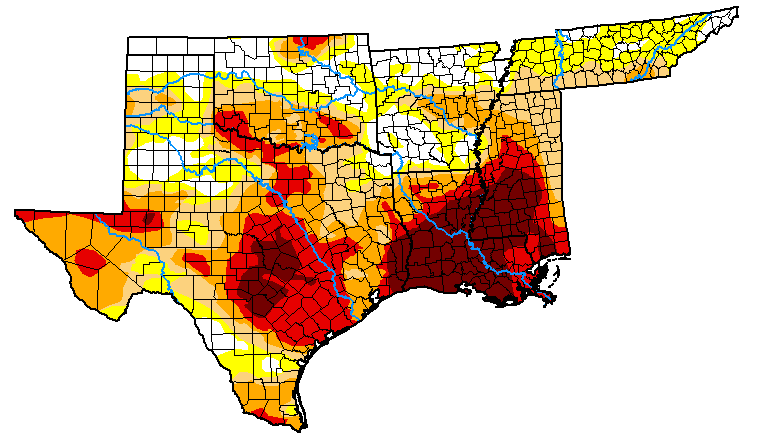

All of Louisiana remained in drought conditions last week – 62 percent in “exceptional drought,” the worst category – while 90 percent of next-door Texas was experiencing some degree of drought conditions, 6 percent of which was “exceptional drought.”

U.S. Drought Monitor map for Oct. 10, 2023. Colors indicate degrees of drought severity, from yellow (abnormally dry) to dark red (exceptional drought).

From north to south, persistent extreme heat continued into October in the middle of the U.S. On Oct. 1, for instance, Minnesota’s Twin Cities Marathon, expected to feature 300,000 runners this year, was canceled because record-setting high temperatures that were expected “do not allow for a safe event for runners, supporters and volunteers.” Three days later in Central Texas, Austin set a new daily high-temperature record for Oct. 4 of 100 F.

The lingering extreme heat has not been confined to North America by any means. The Washington Post reported on Oct. 9 that “October is off to a historically warm start over much of Europe after its hottest September on record.”

So far this month, thousands of locations have set calendar day record highs, and scores have also set records for the entire month of October. Spain, France, Poland, Austria and Slovenia all posted their highest October temperatures.

Weather historian Maximiliano Herrera described the early October heat as “one of the most extreme events” in the continent’s history based on the “quantity of records,” the size of the area affected and the “insane” margins by which records were surpassed.

The Times, one of the U.K.’s leading newspapers, cast a globe-spanning eye at “temperatures rising from Canada to Antarctica” on Sept. 1. Regarding Central and South America and Australia, The Times’ meteorological columnist Paul Simons wrote:

Mexico is roasting in a withering heatwave with 47.5 C (117.5 F) recorded at Chinipas de Almada. This counts as one of the most extreme heat events in climate history at this time of year — only Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have recorded a temperature that high in the last week of September. There is also record heat in the Caribbean and in Central America. Costa Rica reached 37.8 C (100 F), a national record for the month.

It is early spring in the southern hemisphere but already there are brutal heatwaves. Brazil is seeing 40 C (104) or more in some parts and heat is also hitting Bolivia, French Guyana, Paraguay and Argentina, and Peru has equalled its September record with 40.6 C (105 F). In Australia, temperatures have reached almost 42 C (107.6) and both Perth and Sydney have broken their September records.

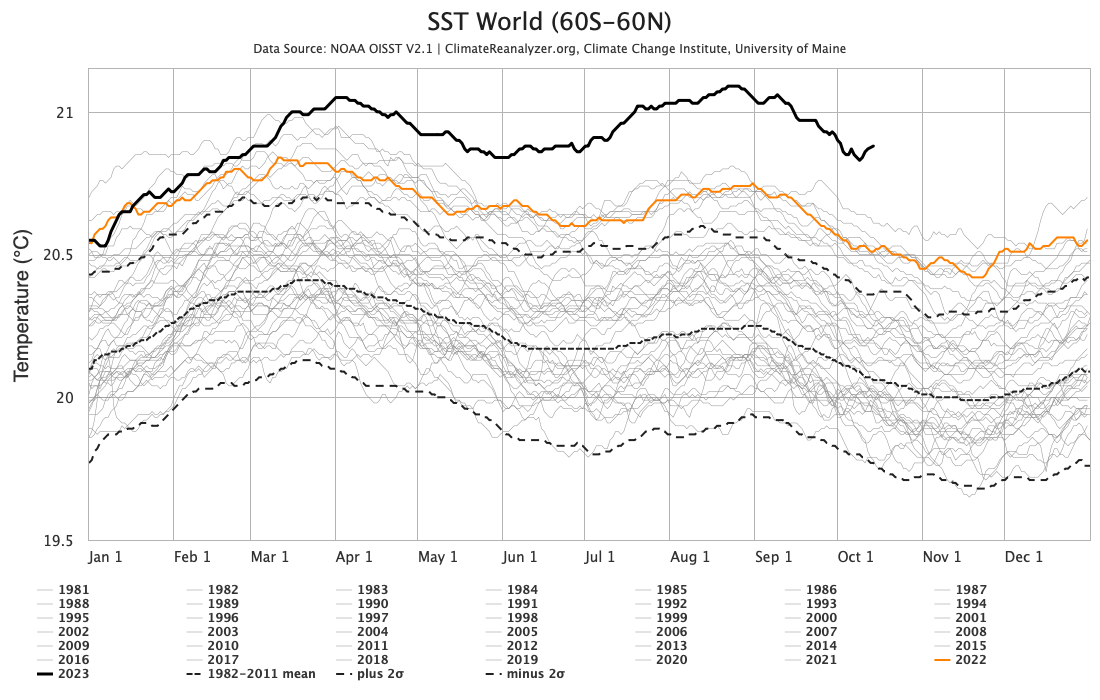

Most manmade atmospheric warming is absorbed by oceans, which has mitigated the rise of land temperatures but contributes to sea-level and rise boosts tropical storms, as with Hurricane Hillary this year. This chart by the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute shows that since mid-March, the 2023 average sea surface temperature (bold black line) has remained well above the previous record-high average in 2016. The orange line shows the average in 2022. Scientists have recorded a number of “marine heat waves” this year, as well as sea ice around Antarctica at the lowest winter levels ever.

Does 2023’s heat mean climate change is accelerating?

Prominent climate scientists say they expect 2024 to be as hot as 2023, if not more so, as a persistent El Niño, a natural weather pattern, continues adding warmth to a human-warmed atmosphere. Beyond next year’s expected conditions, however, they’ve been discussing a more significant long-term question: Do recent and current conditions signal that the manmade climate warming that researchers have been projecting and recording, along with its attendant impacts like drought, wildfires and floods, is speeding up?

Last week, the Washington Post’s global weather writer Scott Dance wrote an article examining how El Niño and other possible factors – that is, in addition to human-caused warming – may have been influencing this year’s extreme, multi-continent heat: “Record warmth is to be expected as greenhouse gases heat up the planet. But a spike in global temperatures observed in September was so much more dramatic than past extremes that some climate scientists said it defies a simple explanation.”

In July, The Economist provided a detailed overview of reasons that global warming may be accelerating. One possibility it cited: Earth scientists at Britain’s Royal Holloway University argue that increasing emissions of methane, an especially potent heat-trapping pollutant, may not all originate in leading suspected sources linked to fossil fuels and agriculture:

The researchers think that the surplus may be coming from the growth of tropical wetlands, whose plants produce the gas when they rot. This is one candidate for the mechanism that drives the methane spikes seen at the end of ice ages. If true, it opens up the possibility of a feedback loop starting today similar to the ones that seem to have operated in the past. More methane means more warming, which means more wetlands, and therefore more methane.

Texas A&M’s Andrew Dessler wrote in a blog post on Oct. 10 that it’s dangerous to infer a sudden and lasting surge in manmade warming’s pace from 2023’s “short snippet of the climate record,” because “short-term climate variability” can be misleading.

[…] If we continue to see extraordinary warmth for the next three to five years, even after the current El Niño ends, we’ll know that something fundamental has changed in our climate system. However, I suspect that things will settle down and the climate will continue evolving along the [warming] pathway charted by the climate models.

This provides me no comfort, though. My biggest fear is not that the physical climate system spins out of control, but that we reach tipping points in the economic and social systems due to climate change, such as an implosion of the insurance market. The impacts of climate change are strongly non-linear, so our society could be much closer to a catastrophic tipping point than we realize. That’s what keeps me up at night.

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.