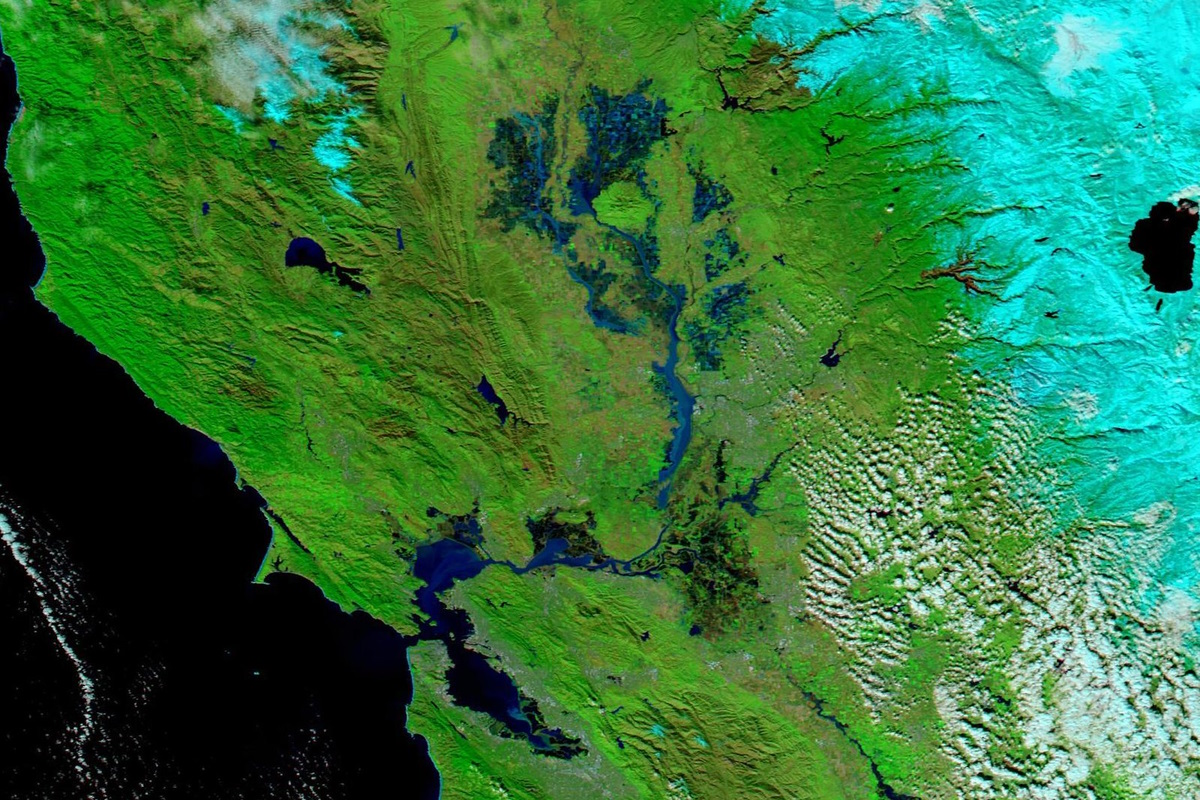

NASA Terra image of flooding in California’s Central Valley, Jan. 17, 2023. Stuart Rankin, CC BY-NC 2.0, via flickr

TCN Digest articles present our summary selections of recent news with a common theme or close connections, along with explanatory context and links for further reading.

It’s already the middle of January now, so 2022 has well and truly given way to 2023 (unless you prefer the lunar calendar, in which case the new year will start in just a few days).

Either way, a review of news developments reported around the turn of the year provides both a retrospective image of climate change in 2022 and some indications of what to expect in 2023’s months ahead.

In summary: It’s safe to expect more major news about weather extremes and the roll-out of parts of the biggest government attack on climate change in the nation’s history.

Climate and emissions in 2022

Experts warn that months-ahead forecasts are always risky business and that the continuing march of weather extremes worsened by climate change won’t proceed in an unbending line. Still, year-end reports gave no sign of abatement in 2022 or hint of that happening in 2023.

Some key indicators in relevant news items:

Driven by extreme summer temperatures in some regions, the earth’s global average temperature last year meant the past eight years were the hottest on record, and that 2022 was the fifth-hottest year.

For the fourth straight year, the average global ocean temperature reached a new record high. Scientific American: “It’s an ominous sign of the speed at which the world is warming. The world’s oceans are massive heat sinks – they absorb as much as 90 percent of the excess heat in the atmosphere.”

An annual federal report ranked 2022 as the United States’ third most economically costly year in terms of climate and weather damage ($165 billion) since officials began keeping such cumulative-cost records in 1980.

The research group Rhodium calculated that U.S. emissions of climate-disrupting greenhouse gases, mainly from fossil-fuel use, had increased by 1.3% in 2022 from 2021, though the economy’s “carbon intensity” went down.

Weather extremes in 2023 – and beyond

A return of the naturally cyclical El Niño weather pattern is expected to combine with human impacts on the climate system. The Guardian on Jan. 16: “Early forecasts suggest El Niño will return later in 2023, exacerbating extreme weather around the globe and making it ‘very likely’ the world will exceed 1.5 C of warming. The hottest year in recorded history, 2016, was driven by a major El Niño.”

Columbia University’s James Hansen, one of the world’s most prominent climate scientists, and his colleagues reported last fall that El Niño’s return will mean that “2024 is likely to be off the chart as the warmest year on record.”

Turning attention from the latter part of 2022 to the first weeks of 2023, it’s instructive to consider California’s massive flooding from a succession of “atmospheric river” storms that began sweeping in from the Pacific in late December. Such a series of heavy rain events is a natural, if uncommon, phenomenon that’s likely to happen more frequently, thanks to climate change, scientists are warning.

A state flood-protection plan for California’s Central Valley, approved last month, “presents a stark picture of the dangers,” the Los Angeles Times reported on Jan. 18: “Giant floods like those that inundated the Central Valley in 1861 and 1862 are part of California’s natural cycle, but the latest science shows that the coming megafloods, intensified by climate change, will be much bigger and more destructive than anything the state or the country has ever seen.”

Government action (1)

Last year saw Congressional passage of the landmark Inflation Reduction Act, with $391 billion in clean-energy spending that made it by far the biggest governmental effort to reduce and guard against climate change in U.S. history. The law supplements two other major climate-action measures signed by President Joe Biden – the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law with $138.5 billion and the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act with $67 billion.

No one expects anything from Congress this year that would be remotely comparable in adding further impetus to the nation’s transition away from fossil fuels. Republicans in November gained narrow control of the House. The Inflation Reduction Act had passed without a single Republican vote last August.

NPR noted on Dec. 30 that California Republican Rep. Kevin McCarthy, subsequently elected as House speaker, has revealed plans that include both “boosting domestic oil and gas drilling” and “building climate-friendly energy sources like nuclear and hydropower.” Such measures, if passed by the House, would face an uncertain future, at best, with a Democrat-controlled Senate and a Democrat wielding the presidential veto power.

Then there’s another complicating factor in the congressional outlook – the power of a small contingent of far-right House Republicans instrumental in McCarthy’s election as speaker. His committee appointments for several of them this week provided “the latest evidence that the new Republican majority is driven by a hard-right faction that has modeled itself in former President Donald Trump’s image, shares his penchant for dealing in incendiary statements and misinformation, and is bent on using its newfound power to exact revenge on Democrats and President Biden,” the New York Times reported.

Trump, like many of the most conservative members of his party, was notably hostile to climate science and renewable energy during his term in office. Many conservative Republicans’ dislike for renewables has grown since Trump assumed office five years ago, according to polling results released in mid-December by Yale and George Mason universities:

“There is…evidence of increased political polarization in climate policy support over the last five years. Conservative Republicans are much less supportive of funding research into renewable energy today (52% in 2022) than they were five years ago (71% in 2017), and the difference in support between liberal/moderate and conservative Republicans has grown by 10% points (from a difference of 15% points in 2017 to 25% points in 2022).”

Texas legislators in Austin, with conservative Republicans still firmly in control after last November’s elections, have consistently refused to pass climate-action proposals for years. Texas is the leading wind-energy state, thanks in large part to bipartisan legislation in 1999, but don’t expect renewables-boosting measures to pass in this year’s session of the Legislature.

Luke Metzger, a veteran Austin-based campaigner in his job as executive director of the Environment Texas organization, told Texas Climate News he expects to be in a defensive posture this year when it comes to energy legislation, focused on fending off attacks on renewables that have been promised or already filed as bills.

Government action (2)

Despite all that, major government action against climate change will occur this year, thanks to the three big federal laws that Biden signed in 2021 and 2022. Their dedicated climate-action funds will begin flowing in earnest this year toward a wide range of purposes.

One example with particular pertinence in Texas, resulting from its long history of oil and gas exploration and production, is a ramping-up program to use funds from the 2021 Infrastructure Law to plug so-called “orphaned wells.”

These abandoned oil and gas facilities without a solvent owner of record – more than 120,000 documented nationwide – are blamed for leaking climate-warming methane as well as other environmental problems including groundwater contamination and emission of toxic gases.

On Jan. 10, Interior Secretary Deb Harland announced she was establishing an Orphaned Wells Program Office to implement the effort. Last year, her agency announced initial allocations of $560 million to 24 states to begin work toward plugging, capping and reclaiming orphaned wells, including 800 in Texas.

Meanwhile, in a major bid to replace some of the vehicles on the nation’s roads and highways that are powered by gasoline from non-orphaned wells, the existing federal program offering tax credits for buying new electric vehicles was overhauled at the start of the year.

The changes, which stem from the far-reaching and big-spending climate provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act, establish new and complicated rules to qualify for a $7,500 tax credit for a new EV or plug-in hybrid. For details, we’ll refer you to NPR’s Jan. 13 explanatory article, which warns readers at the top that with the redesigned rules meant the program “got complicated. Really complicated.” Well, no one said the transition to cleaner energy would be easy.

Starting on Jan. 1, the Inflation Reduction Act is also now providing rebates and tax credits to consumers for an assortment of other high-dollar purchases. It’s all aimed at helping the U.S. meet Biden’s goal of reducing buildings’ carbon footprint by half over the next nine years, especially through electrification substituting for in-house use of natural gas.

Vox explained the rebates and credits in a Jan. 3 article:

“There’s money for rooftop solar; electric vehicles, clothes dryers, stoves, and ovens; heat pumps for heating, cooling, and hot water; electric panels and wiring. The law also includes programs that cover the costs of insulation and weatherization to cut a building’s energy usage.

“Not everyone will need to replace their furnace, car, or stove in 2023. But even if you aren’t planning to do so, or you don’t own your home, there are ways the IRA’s incentives can apply, and it’s important to start thinking about them early to take full advantage.”

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.