Driven by wind gusts as high as 80 mph, the Parker Creek Fire raced along a linear path through Oldham County on Dec. 15, 2021. @AllHazardsTFS/Texas A&M Forest Service

Trauma from ten years ago got rekindled for Bastrop County residents last week when a controlled burn at Bastrop State Park raged out of control in warm, windy conditions. The blaze on Jan. 18 scorched 812 acres and forced some 250 families to evacuate. Embers from the controlled burn most likely caused the fire, according to state officials, though the cause is still under investigation.

Texas Parks & Wildlife is reviewing why the prescribed burn was carried out in such fire-prone weather.

The Bastrop area is still scarred by memories of the state’s most destructive fire on record, which ripped across eastern parts of the county in the first week of September 2011. The $325-million Bastrop County Complex Fire devoured 1,691 homes, roughly 10 times more than any other fire in Texas history.

The imperfectly controlled Bastrop burn of Jan. 18 could be an omen as much as an echo. Texas’ warmest fall and early winter on record sucked moisture from the landscape throughout the northwest two-thirds of the state. Paltry rains have done little to help. Now Texas is hurtling toward a late winter and spring when unusual heat and dryness will be favored by the climate phenomenon known as La Niña.

“So far, we’re running drier and warmer than one would expect, even with a La Niña,” said state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon.

La Niña – a periodic cooling of the eastern tropical Pacific – tends to produce a chain of weather/climate reverberations that include dry, mild winters from the Southwest into the Southern Plains, including Texas.

La Niña was also in place last winter, but that’s not what stands out for most Texans. Instead, it’s the two weeks in February when the state was hit by a catastrophic Arctic blast – the nation’s costliest winter storm in history, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The vast bulk of the event’s $24 billion in damage and 226 deaths occurred in Texas.

It’s easy to see why that cataclysm dominates recollections of a winter that otherwise wasn’t especially harsh. In fact, the first half of the Texas water year, from October 2020 through March 2021, ended up warmer and drier than the 20th-century average, even with that Arctic blast in the mix.

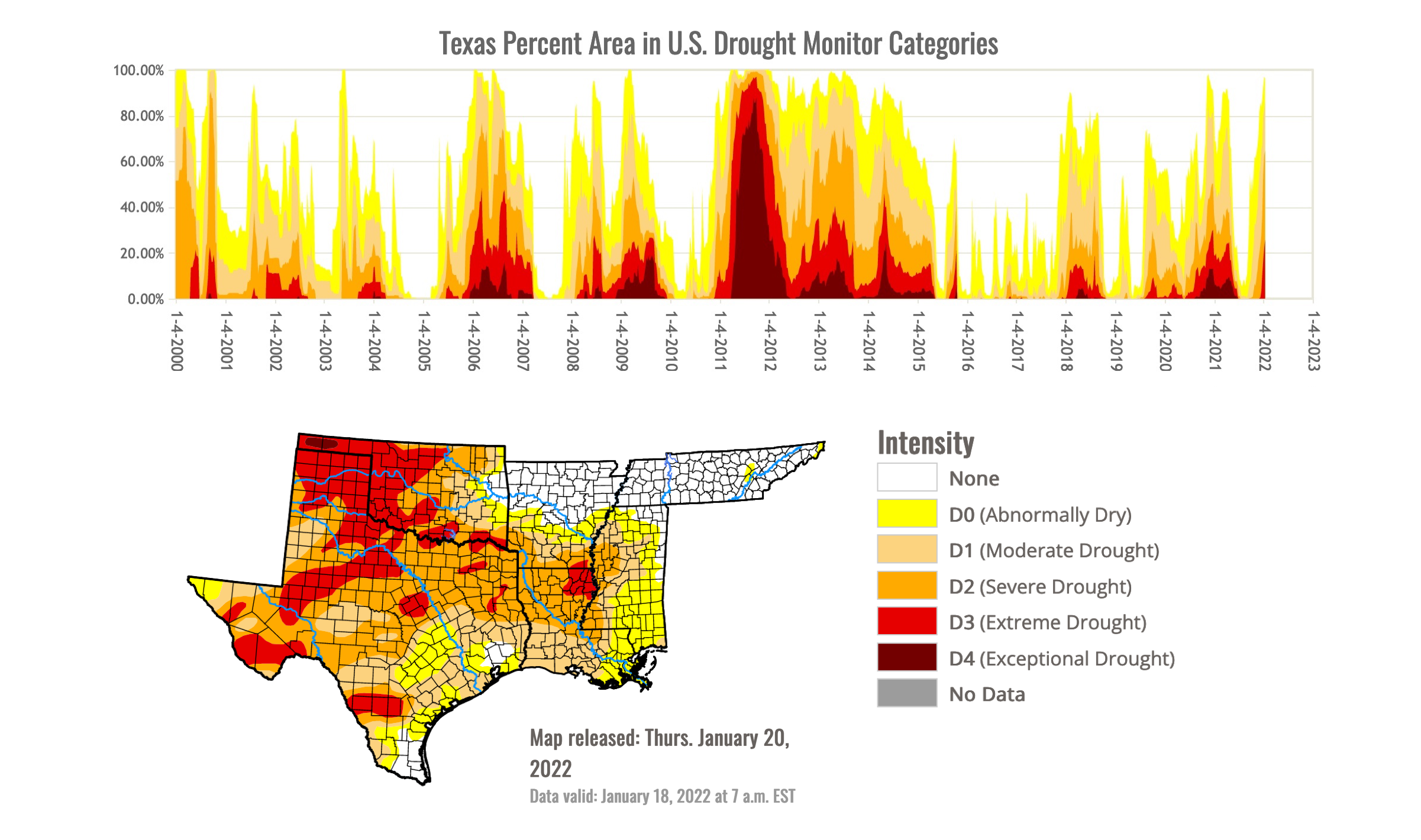

This winter, it hasn’t taken long for extreme warmth and widespread dryness to push Texas into drought. The percentage of state land covered by severe to exceptional drought soared from less than 1% on Oct. 19 to nearly 65% on Jan. 18, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The last time so much of the state was covered by drought this intense was May 2014.

A time series of Texas drought by intensity (top), extending from 2000 (left) to 2022 (right), shows the rapid spike of drought conditions over the last few weeks. Severe to exceptional drought (D2-D4) covered nearly all of northern and western Texas (bottom) as of Jan. 20. U.S. Drought Monitor/National Drought Mitigation Center

What moisture there is has been concentrated in southern and eastern Texas even more than usual, leaving much of western and northern Texas increasingly parched. For the water year thus far (Oct. 1, 2021 – Jan. 21, 2022), Houston and San Antonio were actually somewhat wetter than average, but Midland was at its second driest on record.

More noteworthy has been the unusually high temperatures statewide, which have greatly hastened the landscape dry-out. It’s been the warmest water year on record thus far at Amarillo, Lubbock, and Dallas-Fort Worth, and the second warmest in Midland, Wichita Falls, and Houston, according to NOAA data.

The wildfire threat has jumped in tandem with drought, as borne out in Bastrop County’s recent near-disaster. A few weeks earlier, on Dec. 15, high winds in the Texas Panhandle produced by a powerful storm system in the Central Plains led to extreme fire behavior.

West of Amarillo in Oldham County, the Parker Creek Fire carved out an arrow-like 11,000-acre swath that at one point was 14 miles long but just a half-mile wide.

Lurching into drought once more

The 2011 Bastrop fire disaster was stoked by the hottest and driest summer in Texas history. That year’s vicious drought wasn’t fully quenched until 2015.

If those parched years seem more distant than they are, it’s probably because torrential rain has more recently dominated the Texas weather and climate landscape. In 2017, catastrophic Hurricane Harvey pummeled the Rockport area with Category 4 winds, then left massive flood destruction from Houston to Port Arthur. Harvey dumped rainfall of up to 60.58 inches in Nederland, the most recorded in any U.S. tropical cyclone.

Other headline flood events soaked the state throughout the latter 2010s.

The U.S. National Climate Assessment of 2018 reiterated what longtime Texans know all too well: “The [Southern Plains] region is vulnerable to periods of drought, historically prevalent during the 1910s, 1930s, 1950s, and 2010–2015, and periods of abundant precipitation, particularly the 1980s and early 1990s.”

Texas reservoirs are still benefiting from rains that predate the current drought. Some four out of five state reservoirs are between 70% and 100% full, said Dan Hunter, the assistant commissioner for water and rural affairs of the Texas Department of Agriculture. He was speaking at the Texas Alliance for Water Conservation’s eighth annual TAWC Water College, held Jan. 20 in Lubbock.

The state’s notorious natural swings between wet and dry conditions make the flush years a bigger challenge when it comes to setting longer-term water policy, according to Hunter.

“When it’s wet,” he said, “we tend not to think about the problems we’re facing.”

Even in Texas, swimsuit weather on Christmas Eve is not normal

December 2021 came in with a statewide average temperature of 59 degrees F. That’s more than 5 degrees above any other December average in Texas history going back to 1895, as archived by NOAA. (Patchier data from further back suggest that December 1889 may have rivaled 2021, according to Nielsen-Gammon.)

|

“…Projections [for Texas] indicate drier conditions during the latter half of the 21st century than even the most arid centuries of the last 1,000 years.” – John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas state climatologist

|

Wichita Falls took the cake on Dec. 24, soaring to an absurd Christmas Eve high of 91. Not only was this a monthly record for the city, it was warmer than anything ever observed there in November or January as well.

All told, December 2021 saw more than 5,300 daily record highs nationwide. The records were most concentrated across the Southern Plains, including Texas.

Such regional heat waves (or “warm waves”) are prime fodder for climate scientists who carry out what’s called attribution research. This growing discipline uses computer models to simulate large-scale weather extremes in our current atmosphere, as well as in a model atmosphere designed to replicate preindustrial conditions. By running both types of models many times, with tiny changes to the starting-point conditions, researchers aim to assess whether a particular weather event is more likely as a result of human-caused climate change – and if so, by how much.

The 2011 Texas drought was among the first high-impact heat waves to be examined by attribution research. The first batch of studies came to a mixed verdict on the relative role of climate change in driving the event, with the intense heat most likely boosted at least somewhat by long-term warming.

More recently, the 2018 U.S. National Climate Assessment concluded that as this century unfolds, “temperatures similar to the summer of 2011 will become increasingly likely to reoccur.”

Climate change doesn’t play out in a vacuum, of course. The state is filling with more and more people – including many who lack experience with the state’s natural climate swings, much less the ones now evolving under human influence. Given that Texas now has about 5 million more residents than it had when the state was hit by 2011’s summer of unprecedented heat, drought, and fire, it’s safe to conclude that millions of Texans might soon see the state as drought-gripped as they’ve ever experienced it.

The 2021 Regional Water Plan from the Texas Water Development Board hinges on a projected population increase from near 30 million in 2020 to 42 million by 2050 and 51 million by 2070.

A 2020 study led by Nielsen-Gammon warns that the booming state may be in for grueling climatic times: “…projections indicate drier conditions during the latter half of the 21st century than even the most arid centuries of the last 1,000 years.”

The prospects for later this year

For the time being, according to Nielsen-Gammon, “the people who have to do something [about the state’s emerging drought] are already doing it.

“Ranchers are providing supplemental feed and maybe even water. Winter wheat growers are watching their crops struggle. Other farmers are praying for rain for their spring crops and making contingency plans if rain doesn’t show up soon. And domestic water use doesn’t pick up until April, so there’s still time to turn things around before ordinary households have to take action, aside from just being conscious of not wasting water.”

In line with La Niña expectations, NOAA’s latest spring outlook (issued January 20) is for Texas to lean warmer and drier than average. Looking further out, there’s always the chance that an El Niño event will arrive next winter, which would certainly raise the odds for rain (as would one or more tropical cyclones this summer and fall, provided they move far enough inland).

It’s just as possible that La Niña could return for a third consecutive winter. Right now, the odds appear roughly even for El Niño and La Niña by late summer, with a slightly greater chance of neutral conditions. It’ll be a few more months before forecasters have a better handle on what to expect in winter 2022-23.

Science writer and meteorologist Bob Henson is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. He is the author of “The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change.”

John Nielsen-Gammon is a member of TCN’s volunteer Advisory Board. Members have no authority over our editorial decisions.