Kemp’s ridley sea turtles in Rancho Nuevo, Tamaulipas, Mexico 2017. The endangered Kemp’s ridley species is the world’s smallest sea turtle. It mainly nests at Rancho Nuevo and other sites on Mexico’s Gulf coast, with some nesting in Texas. Hrchenge, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikipedia

Texas is no stranger to extreme weather events – the nasty party trick of climate change and an unhappy fact of life even before human-caused global warming.

Most of Texas froze during the record-setting frigid temperatures of Winter Storm Uri in February, with temperatures plunging well below freezing across virtually all of the state, in some cases for days on end. Scientists are trying to figure out whether that event or others like it may be linked to climate change.

While this summer has been relatively mild so far (by Texas’ famously hot standards), predictions call for the state to experience hotter and longer ones as climate change progresses.

These extremes take their toll not just on humans, but on native plants and animals as well.

February’s brutal freeze

In an online Texas Master Naturalist seminar held in April, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department staff reported on how the February ice storm affected Texas wildlife. The known toll numbered in the hundreds of thousands of animals.

TPWD ornithologist Cliff Shackelford noted that birds are built for cold weather, with feathers (think down coats), fat stores, and the ability to adjust their metabolism while sleeping, seek shelter or leave an area. But Uri covered an unusually large area and lasted long enough that birds needed to replenish those fat stores.

Through the department’s Texas Nature Trackers program, volunteers reported wildlife killed by the freeze across the state on iNaturalist, a smartphone app. More than 7,000 volunteers reported 250,000 individual animals killed by the storm, including birds, bats, turtles, and fish.

The significance of those numbers depends on the overall population of a particular species and how it is trending, Shackelford said. He added that birds face greater risk from other weather events, including hurricanes, high winds, heavy rains (especially during breeding season for grassland birds), and drought.

Droughts deliver a double whammy – birds cannot find food to feed their young during the event, and many plants fail to grow the next season, leaving them without shelter.

TPWD bat biologist Nathan Fuller reported that the freeze killed significant numbers of Mexican free-tailed bats. While these bats are migratory, some remain in Texas all winter. Bats can endure brief cold spells, but again, the problem with Uri was how long it lasted.

Bats were too cold to forage, Fuller says, and used up their metabolic water and stored fat, likely perishing from dehydration or starvation. Current populations are fairly large, but the storm could have had a serious effect in some areas.

More than 10,000 cold-stunned sea turtles were recorded by the Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network during February. Texas A&M Sea Grant agent Tony Reisinger told Texas Climate News that this number represents only those found.

“There were many areas where we could not go, so we don’t really know what was out there,” he says. “Experts think every sea turtle in Texas was affected in some way or another by the storm.”

Sea turtles cannot regulate their body temperatures and when the water temperature drops below 50 degrees, they become unable to swim and end up floating at the surface. That makes them vulnerable to boat strikes or washing ashore, where they can die of shock or predation.

Native plants seem to have fared well, Craig Hensley, who coordinates Texas Nature Trackers for TWPD, reported to the seminar.

Agarita bushes lost blooms and therefore fruit for the year, prickly pear suffered some die-back, and trees experienced loss of branches and splitting, particularly Ashe juniper and live oak. But the blanket of snow protected a lot of natives that were just emerging from the ground, he said, adding that the freeze highlights the benefit of native plants best suited for local conditions.

Documenting individual dead animals is useful but does not reveal a lot about population-level effects, reported TPWD state mammologist Jonah Evans. For many species, scientists have no idea what percentage of the population the reported deaths represent. Evans did perform some simple analyses and for every species checked, found reports of live individuals in the same area where there were reports of multiple mortalities.

“The most important lesson to me is that healthy populations are resilient and able to sustain major losses from time to time, when those losses could be bad news for species already at risk or declining,” he told the seminar.

And while Uri was a record-breaking storm that gained a lot of attention, he urged focusing efforts on ongoing threats to wildlife such as loss of habitat, introduced species and emergent disease. One way that wildlife advocates are currently doing that is by working for passage of legislation called the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act.

Increasing summer heat

Texans may find themselves wishing for a bit of Uri’s chill, based on predictions for significant increases in future summer temperatures.

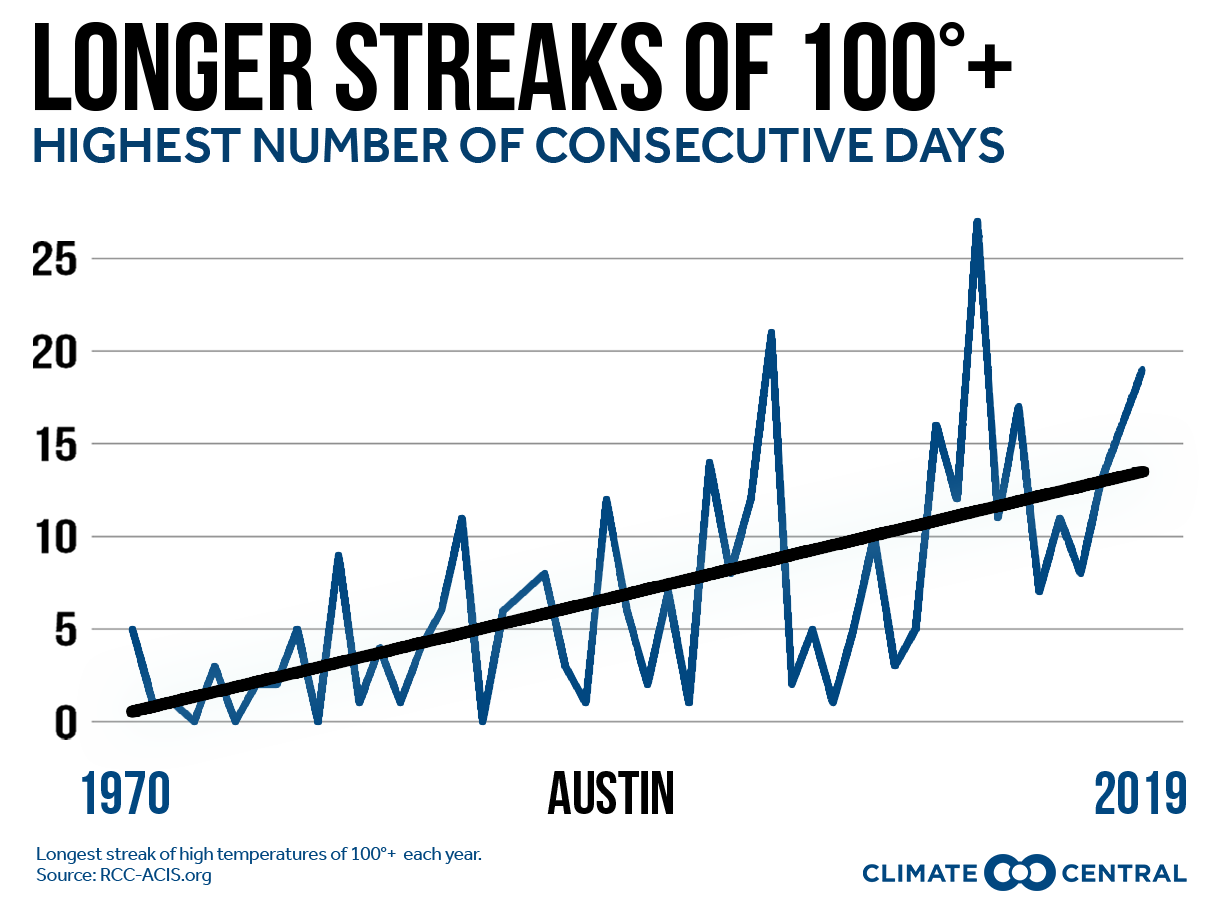

The nonprofit research organization Climate Central analyzed 51 years of summer temperature data in 246 U.S. locations and found that roughly 95% saw increases in their average summer temperature. Nine of the 10 fastest-warming summer locations were in the Western U.S. and Texas, with El Paso landing in the top three.

Climate Central

Of 242 cities analyzed, 74% are experiencing longer stretches of extreme heat compared to 50 years ago. Texas has nine of the 10 cities recording the biggest increases in their longest heat streaks, all of more than 10 consecutive days.

A growing body of research documents the effects of increasing heat and other extreme weather on wildlife worldwide, including dramatic population declines and even local population extinctions.

One study gathered more than 140 scientific studies on the topic and concluded that summertime is quickly becoming deadly. Even when temperatures do not kill animals outright, related shifts in their physiology make them more vulnerable to other stresses. More intense and longer heat waves during pre-reproductive development can reduce an animal’s lifetime reproductive success.

As previously reported in TCN, warmer temperatures could make reproduction increasingly challenging for sea turtles; the temperature during egg incubation determines sex of hatchlings, with warmer temperatures producing more females. Scientists at Rancho Nuevo, Mexico, the primary nesting beach for the highly endangered Kemp’s ridley, say temperatures there already have risen high enough to produce only females.

Plant communities feel the heat as well. A study analyzing some 20 million records of more than 17,000 plant species throughout the Western Hemisphere found that, since the 1970s entire plant ecosystems have changed to include more species that prefer warmer climate, a process called thermophilization. Plants favoring cool temperatures are either moving to higher elevations and latitudes, or locally going extinct.

Study author Ken Feeley, a University of Miami biology professor, told Texas Climate News that of the 200 or so ecoregions in North America, about two-thirds show increased abundance of heat-loving plant species, including most in Texas.

“The pattern we’re observing is increasing relative abundance of heat-loving species,” he said. Whether that occurs because heat-tolerant species increase, cold-loving species decrease, or a combination of the two depends on location. “A primary thing happening is loss of cold-loving species, though. It is getting too hot for them, and they are dying off and their ranges contracting.”

The implications go far beyond the loss of certain plants, Feeley says, as plants provide food and habitat for wildlife. As plant communities transform, so will the animals that need them.

“In general, any sort of change in plant communities causes changes in the diversity of that community, in terms of both the animals it can support and services it can provide people,” he says.

“In some cases, you might get lucky and the changes are good, but in most cases they are negative. Human ecosystems adapted to conditions over the past several thousand years, so any change is likely to be a shock and have negative consequences, at least in the short term.

“The big finding is that this is a really widespread pattern, from the most remote sites in the Amazon to Central Park. Climate change is a unique phenomenon occurring everywhere, with consequences everywhere.”

Melissa Gaskill, an independent science writer based in Austin, is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News.