Thinking ahead to what (and whether?) you may be driving – may have parked in your garage or driveway or parking lot – a few years from now? Like, for instance, in 2035?

Only with “robust” public policy initiatives as yet not on the books (and perhaps not even on the horizon?), could you find yourself choosing, whether a new passenger car or truck, from among only all-electric vehicles? That’s the case if the findings of a newly released analysis from the University of California, Berkeley, and colleagues are to be believed.

The new reports, by Berkeley scholars and colleagues from the nonprofit group Energy Innovation, find (spoiler alert here: big caveat coming) that with “the right policy” across a number of areas, “all new cars and trucks sold in the United States can be powered by electricity by 2035.” Minus those policy adjustments, the researchers warn, “most of the potential to reduce emissions, cut transportation costs, and increase jobs will not be realized.”

(The sweeping studies described in this piece were made public just prior to news reports that the Biden administration was about to commit to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by about 50% by just the end of this decade, requiring “profound changes at home,” the Washington Post reported.)

Technical and economic hurdles are “challenging but achievable”

“Political will, policy, and consumer acceptance – not technical or economic feasibility – are the largest barriers” to be overcome, the report authors write at one point.

In what must seem a blanket endorsement of EV proponents, they say their analyses demonstrate that improved battery technology, costs, manufacturing scale, and industry ambition will accelerate rapid electrification of cars and trucks. And they are not awed by the need to build the extensive battery charging infrastructure needed to support a transition to electric vehicles: All that infrastructure “can be built quickly and cost-effectively,” they write: “The pace of the required infrastructure scale-up is challenging but achievable, and the costs are modest compared with the benefits of widespread EV deployment.”

And, oh yes, the related public health benefits will lead to 150,000 fewer premature deaths and a savings of $1.3 trillion in environmental and health costs over the next three decades.

Jobs? That too, not a problem. In addition to saving consumers $2.7 trillion by 2050 – about $1,000 annually per household – rapid electrification of new cars and trucks will lead to a net increase of more than 2 million jobs by 2035. Again that nagging “if”: If it’s all combined with a 90% clean energy grid. That, the report authors explain, means that given normal demand periods, “existing hydropower and nuclear capacity, approximately half of existing fossil fuel capacity, and new battery storage, wind, and solar is sufficient to meet load dependably with a 90% clean grid.”

And what about periods of high demand and/or low renewables generation? That’s covered too, as the researchers say existing fossil fuel capacity, and new battery storage, wind, and solar are sufficient to meet load dependably with a 90% clean grid. The authors do characterize the 100% EV sales by 2030/2035 and the 90% clean grid goals as “certainly ambitious.”

The authors point to “high upfront vehicle costs and inadequate charging infrastructure” – rather than to technical or economic feasibility – as hurdles to increasing EV sales and faster decarbonization to meet global climate objectives outlined in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

“The case for electric vehicles is stronger than ever before and one of the most exciting findings of this study is the potential for large savings for all households,” said Nikit Abhyankar, senior scientist at Berkeley’s Center for Environmental Public Policy. And, once more, the caveat: “with the right policy and infrastructure,” in which case EV cars and trucks “will be much cheaper to own and operate.”

Another Berkeley senior scientist involved in the study, Amol Phadke, points out in a statement that sales of electric cars and trucks are outpacing earlier forecasts and “already exceeding market projections.” He says “performance and cost of the technology are ready to meet the needs of American drivers today, and the necessary charging infrastructure can be built cost-effectively without straining electricity grids.”

If only national, state, and local policymakers, decision makers, and other leaders could muster the “ambition and leadership.” Minus that, “our vehicle and battery manufacturing industries fall behind in global competitiveness, consumers are saddled with higher costs, and we miss the ever-narrowing window to address the climate crisis and ensure a livable planet,” adds study author David Wooley, a Berkeley public policy professor and executive director of the school’s Center for Environmental Public Policy.

Nettlesome public policy hurdles could be show-stoppers

But alas, there are again and still those nagging public policy obstacles…and too many intransigent policy makers. “With political leadership, policy ambition, and a focus on an equitable transition for all, the U.S. can chart the course for a clean transportation future,” says Sara Baldwin, director of electrification policy for Energy Innovation, the policy partner in the research project, which also involved technical support from GridLab.

Research partner Energy Innovation’s companion policy report details numerous legislative and regulatory policy approaches needed to incentivize the technical and economic components. Many of these ideas are likely to be reflected in the Biden administration’s sweeping proposed policy agenda once details of it become clear.

It won’t be easy, the researchers point out, particularly given profound philosophical, ideological, and political divisions in the policy community, especially at the national level, and considering also the virtual certainty of eventual litigation.

Seeing the country (and perhaps also much of the world?) “at a crossroads” with the end of fossil-fuel-powered internal combustion engine vehicles coming into clearer focus, the group’s policy report readily acknowledges an obvious missing link: “We lack a comprehensive clean transportation policy strategy” to steer us toward a cleaner transportation tomorrow. (Memo to files: Newly confirmed Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg – take note.)

In the policy report, the authors review options ranging from a “business-as-usual” no-new-policy scenario to one that some might perceive, rightly or wrongly, as somewhat utopian: 100% EV sales by 2030 to 2035 in combination with a 90% clean electricity grid. On that latter scale, optimism reigns in terms of the positive climate, environmental, economic, jobs, and public health effects.

Too good to be true? Not so fast, report authors caution, recalling the experience of society’s having jumped relatively lickety-split from horses and carriages to gas-powered cars. But there are more arrows too in their quiver – they say the potential for bold action, albeit not a universal objective in today’s highly-politicized Washington, is “bolstered by the widespread support among Americans for more aggressive policy action” on climate change and the public’s favorable attitudes toward EVs.

Clearly with Biden administration officials in mind as they pursue their sweeping infrastructure legislative proposal and other aggressive climate change actions, the Energy Innovation researchers couch their study as “a guide and reference for policy makers.” They spread the responsibilities also to state and local governments and to utilities.

And they include an important and timely caveat: Environmental justice, social equity, and mobility and inclusive processes must be hallmarks of the new policy initiatives they deem necessary. They specifically single out here individuals “disproportionately burdened by health-damaging emissions from trucks and buses” and low- and moderate-income consumers and their communities. (Think here those unlikely to seriously shop car dealer lots for the latest and greatest Tesla.)

Their hierarchy of priority policy initiatives is detailed in a multi-page chart:

- Strong national fuel economy and tailpipe emissions standards for all vehicle classes. The group characterizes these as “the highest priority” for meeting emissions reductions.

- Equity-focused policies and programs reflecting community input from those most adversely affected by transportation pollution – those held back as a result of redlined neighborhoods and frontline and underserved communities.

- Temporary targeted incentives, scaling down as the market matures and as lower costs benefit more and more people and businesses;

- Spending for a “ubiquitous charging network and a modern grid.” Here, the need is to assuage consumers’ and businesses’ concerns and build confidence.

- ‘Made in America’ domestic manufacturing, to help remake automakers as battery manufacturers focusing on EVs, energy storage, and more. A clear goal here: jobs, jobs, and more jobs for workers transitioning out of conventional auto industry jobs.

- Smart electric utility regulations and local government leadership. The group’s motive here: facilitate interconnections and integration of EVs in homes, businesses, and communities in ways that “pay dividends as demand grows.”

It all sets the table for the upcoming debates and controversies – in the wake of the week’s 2021 Earth Day and the two-day remotely conducted climate “summit” – for what could prove to be the definitive turnaround in the U.S.’s international role on climate change. Or else, some might legitimately fear, just more words, followed by too-little and too-late substantive action. Time will tell.

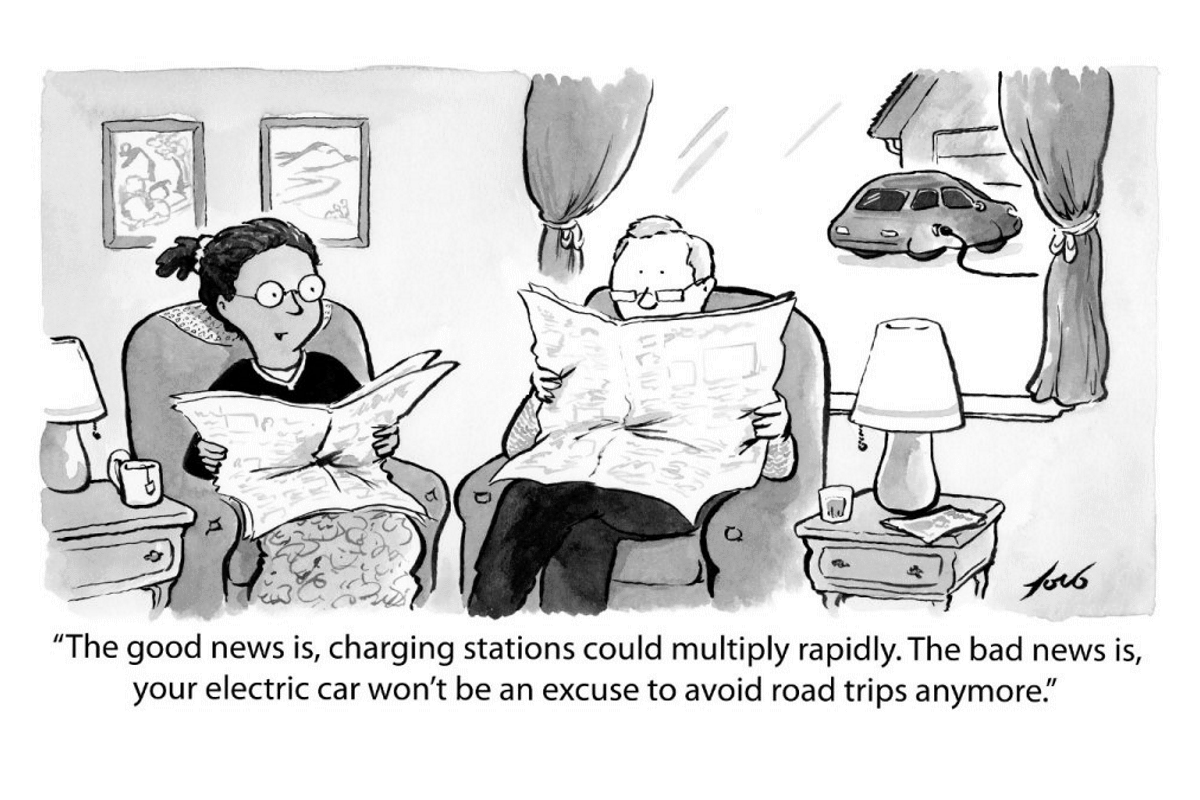

Bud Ward, the editor of Yale Climate Connections, wrote this article for that publication. The cartoon is by Tom Toro, who has published more than 200 cartoons in The New Yorker since 2010.