Solar panels. Martin Abegglen, CC BY-SA 2.0, via flickr

A plan to convert 240 acres of municipal land south of downtown Houston into an electricity-producing solar farm will be a case study of how the country can address both environmental justice issues and climate change.

Once completed, Sunnyside Energy LLC’s Sunnyside Solar Array will be the largest urban solar project in the country. But the significance of the project, approved unanimously by the Houston City Council in January, is less about its size and more about its location – a defunct and once intensely controversial city landfill. That dispute a half-century ago was an early harbinger of today’s increasing focus on “environmental justice” and “environmental racism” and the disproportionate burdens those terms describe.

While it operated, the landfill and a nearby city incinerator released pollution, caused property values in the largely African American Sunnyside community to plummet, humiliated residents. Solid waste disposal in the community led to the death of an 11-year-old child who wandered from a neighborhood park and drowned in an uncovered pond amid dumped garbage. Prominent community leaders have endorsed the solar project – which will be privately funded on the land leased from the city – hoping it can help change the trajectory of the community.

Landfill legacy

One of the proponents, community activist Sandra Massie Hines, was born in Sunnyside and remembers growing up there in the 1960s. Her father worked as a driver for Houston’s sanitation department, and her mother was a stay-at-home mom. Hines became a community activist and earned the nickname “Honorary Mayor of Sunnyside.”

“When I was growing up, there was literally nothing here,” Hines said. “There was grass that would grow so tall it looked like wheat because it was burnt. As far as the eye could see, you could see oil wells, dairy cows, agriculture. You could see industry everywhere.”

Black families, like Hines’ parents, moved to the suburb to flee crime in the city, Hines said. A number of Black-owned businesses opened in the middle-class neighborhood.

Houston’s Sunnyside neighborhood had been developed in Southeast Houston as a segregated Black community in the 1940s. At one point, it was known as “Baby River Oaks” – the moniker a reference to the famously wealthy, mostly white Houston neighborhood. When the city of Houston annexed Sunnyside in 1956, it sited a landfill there, though Houston unofficially began dumping long before the official landfill.

When she was a child, the trash seemed to reach the sky, Hines said.

“The dumping continued, and it looked like the trash went into the clouds,” she said. “I remember wondering how long they would continue doing that. The stench went all over the neighborhood.”

Sunnyside in 1979: Robert Bullard of Texas Southern University took these photos for his Houston Waste Study as he prepared to testify in the landmark Bean v Southwestern Waste Management Inc. case. It was the first lawsuit in the U.S. to allege discrimination in waste-facility siting under civil rights laws. Bullard’s research showed that all five city-owned solid waste landfills were in Black neighborhoods. Top: The Holmes Road Incinerator in the Sunnyside community, which the city had shut down amid intense controversy several years earlier. Middle: Sunnyside Elementary School, located near the incinerator site. Bottom: A landfill at the Holmes Road site, also closed before 1979. Courtesy Robert Bullard

Later, the city built an incinerator near the landfill site. The incinerator was five stories tall, eight with the smokestack. It was the tallest building in Sunnyside. That was even more embarrassing, Hines said. The burning trash turned the sky black. And though garbage burned day and night, the volume never seemed to decrease. The mounds kept growing higher.

“Everybody in the neighborhood got allergies, asthma,” Hines said.

The city shut down the incinerator and landfill in the 1970s, but the capped land was never rehabilitated.

In 1979, another Houston neighborhood filed a lawsuit against the siting of a proposed landfill. That case, Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management, became the first one in the country in which civil rights laws were used to fight the siting of a waste facility.

Robert Bullard, distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Houston’s historically Black Texas Southern University, was an expert witness in the case. Bullard, who came to be known as “the father of environmental justice,” conducted a study that showed that all five city-owned landfills and eight garbage incinerators in Houston, including Sunnyside’s, were placed in Black communities.

“While the landfill and incinerators are no longer in operation, that does not mean that the residuals of that racist past are in the ground,” Bullard said. “The land is still owned by the city, and it’s still sitting there as a legacy of the past.”

Whatever happens to that land, what’s most important is that it’s what the community wants and that their voices are heard, Bullard said.

EPA paradigm shift

Sunnyside’s legacy is what sets the proposed solar project apart from other green energy projects, especially as environmental justice issues have assumed renewed importance on the federal level with the election of a new president who pledged to address them systematically.

On Jan. 20, President Joe Biden signed an executive order creating the first ever White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and ordered federal agencies to create programs and policies to help communities and to invest dollars in clean energy to help communities disproportionately affected by pollution. Bullard is one of the 26 members who were appointed to the advisory panel in March.

It’s part of a paradigm shift at the Environmental Protection Agency and other federal agencies, said Matthew Tejada, director of EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice. Prior to joining the EPA, Tejada was executive director of the Houston grassroots environmental advocacy organization Air Alliance Houston.

Ever since the original 1994 executive order by then-President Bill Clinton on environmental justice, the federal government treated the issue as something to be addressed after the rest of the EPA’s business got done, Tejada said.

“We set national standards, we write national rules, and those are really kind of targeted for the middle of the country,” Tejada said. “There’s long been an acknowledgement that when we make those sorts of decisions, we can’t regulate for the folks that are most impacted because that would be just be too hard.”

The transition that’s underway in the Biden administration begins with appreciating, considering, and focusing on the sorts of challenges that exist in communities with environmental justice concerns, Tejada said.

“We are in a place that we’ve never been before, where not only can we directly address the systems of historic racism but we’re going to address them in a completely different way than the federal government has addressed them before.”

Working with communities like Sunnyside means first making sure they are meaningfully engaged in decisions that will impact them, Tejada said.

“We’ve made progress in the past at EPA, but there’s still a huge amount of work to do on it,” Tejada said.

“It’s up to us to look to the statutory authorities we already have available to us and to re-center our thinking on how we apply those authorities in a new paradigm, where we really challenge ourselves not to think about helping a place like Sunnyside as something that is extra but that is the mission.”

As a result of the pandemic, citizen groups’ meetings with the Biden administration officials have been virtual, giving more people access, Bullard said. Typically, groups that have the means to travel to Washington, D.C., have enjoyed better access to policymakers, he said. While he is optimistic about the new administration’s actions so far on environmental justice, he said he will also be watching developments at EPA’s multi-state regional offices, which include one in Dallas.

Community optimism

Hines and other community supporters of the solar project hope it will be a positive step for a neighborhood that for years had been an environmental sacrifice zone for the city’s garbage. The project calls for land reclamation and a 50-megawatt (MW) solar farm that would be integrated into the state’s power grid. Plans also include a 2 MW community solar array, an education hub, as well as an agricultural center.

“We call the whole project Sunshine in Sunnyside,” Effren Jernigan, a lifelong resident and retired chemical plant employee, said. “Our goal is to let the sunshine of success shine through Sunnyside.”

Jernigan runs a Saturday outdoor STEM program for third through twelfth graders. He’s been teaching kids about solar power and currently is building an indoor solar classroom.

It was through this program that Jernigan met Dori Wolfe, founder of the community solar development company Wolfe Energy and managing director of Sunnyside Energy. Wolfe volunteered to help Jernigan teach kids about solar power.

Wolfe had moved to Houston after finishing work on a 7 MW solar array on a Superfund toxic waste site in Vermont. During a climate change event, Wolfe learned from Lara Cottingham, the city of Houston’s chief sustainability officer, about the C40 Reinventing Cities Competition, a nonprofit initiative “to drive carbon neutral and resilient urban regeneration.” That’s when the idea of the solar array on Sunnyside’s former landfill came to her.

“I did this on 25 acres; why not 250 acres?” Wolfe said, “Why not 10 times as big?”

Wolfe worked with Jernigan, Hines and others to put together a proposal and entered the C40 competition. In August 2019, their project won. Wolfe Energy formed Sunnyside Energy to move the project forward.

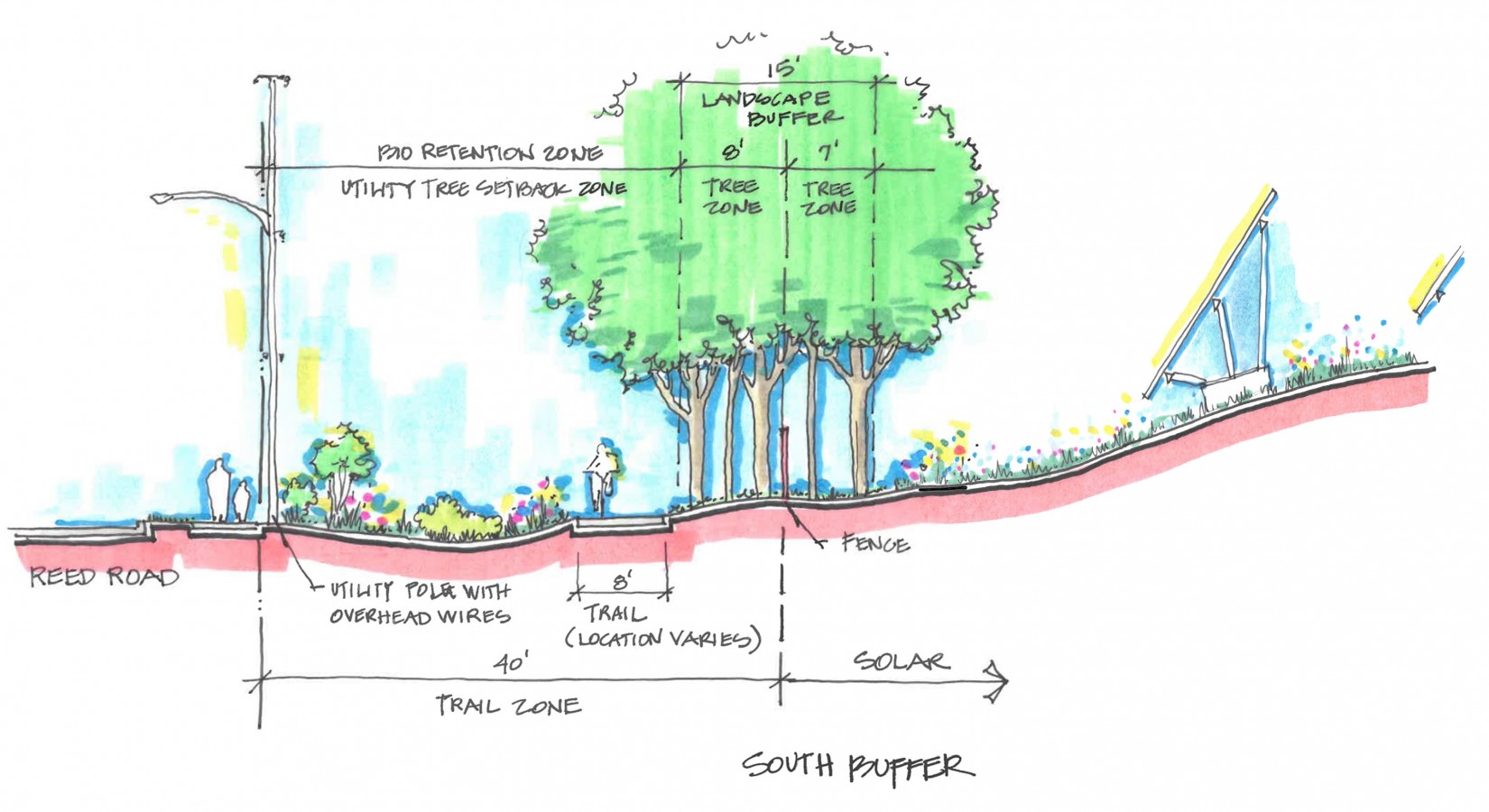

This drawing shows the concept for a vegetated buffer area, including a “trail zone,” between Sunnyside Energy’s solar farm and Reed Road. Before solar panels are installed, restoration of the unmaintained 240-acre’s cover will address methane leakage from the old landfill, the company says. Methane is a powerful climate-warming pollutant. Sunnyside Energy LLC via C40 Reinventing Cities

Under the terms of the lease agreement, the city of Houston will retain ownership of the land, but Sunnyside Energy will be responsible for obtaining permits, construction, operation and maintenance of the project.

The city council lease approval allows Sunnyside Energy to secure necessary state and local permits as well as finalize financing. It will apply to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which operates the electric grid across most of Texas, for a permit to connect to the grid. It will also apply for a land-restoration permit with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

“It’s pretty unusual to have a utility-scale renewable project of any kind within the city limits,” Cottingham said. “Just because it takes so much space. This is one of neat, quirky aspects of Houston. We have a pocket of 300 acres in the middle of the city.”

The city touts the project as another step in increasing solar energy, a key component in Houston’s Climate Action Plan.

“You can have the most efficient building, but without clean energy, you’re never going to meet that carbon-neutral goal,” Cottingham said.

Community Concerns

Not all residents are sold on the project, however. Tracy Stephens, also a lifelong Sunnyside resident, is president of the Sunnyside Civic Club and a community developer for the environmental justice group ACTS, or Achieving Community Tasks Successfully.

Stephens supports the proposed agriculture hub and education center connected to the project. His primary concern is related to the 50 MW solar array that will be connected to the state’s power grid.

Sunnyside residents, like most Texans living in deregulated portions of the state, will still have to buy electricity through a retail provider. Stephens thinks the project might be another example of outside interests making money at the expense of the neighborhood.

“If this is for the community, how is the community going to benefit from it if the power is just going to the grid,” Stephens said. “It’s not like they’re going to offer [the power produced] at a discount to the residents of Sunnyside. That’s like any other energy company.”

Stephens would support the solar farm if the electricity it produces resulted in a discount in power prices for seniors in the neighborhood.

Compared to landfills or pollution-emitting plants that have traditionally been placed in or next to some neighborhoods, there’s no harm in a solar plant, Stephens said, but “they’re going to make money off our backs.”

In an environmental justice framework, the Sunnyside project can’t be just another energy project, Bullard said. It has to create benefits for the people living in Sunnyside, independent of the benefits the entire city will get from having a source of clean power.

“There are benefits that need to accrue, and a solar farm can have that leverage because it would be an economic generator,” Bullard said. “We’re talking about money being made, and some of those benefits need to be shared with the community for upgrading, not displacement or gentrification to the point of pushing people out, but benefits that would accrue.”

For Jernigan and Hines, it comes down to neighborhood pride and putting communities such as Sunnyside on a different trajectory.

Jernigan believes that more community education about the project, which has slowed down because of Covid-19, can help all residents feel comfortable with it. While the main solar farm will feed into the grid, he said, the 2 MW community solar array will be something the community can buy into at a fixed rate, depending on the number of residents that participate.

The food grown in the agricultural hub can help with food insecurity in the community, especially among children and seniors, Hines said. Included in the project plan is also a training program for local residents to learn how to repair and maintain solar panels, another positive impact.

Wolfe believes that the project can be replicated in other communities. She is talking to community activists in Dallas and Austin about similar projects in those cities. Building solar farms provides a way to safely use urban properties including “brownfields” (with real or perceived contamination from past uses) and Superfund sites (on a federal priority cleanup list for toxic waste) – turning them into a source for clean energy while helping disenfranchised communities, she said.

“Not only can we do it here, but we can replicate it. Near every landfill you can generally find a community of high energy burden [where residents spend more than 6 percent of household income on energy costs] and socially challenged through inequities.”

Nushin Huq is a contributing editor of Texas Climate News. She is a Houston-based independent journalist focused on covering energy and the environment.

Reporting for this article was made possible, in part, by a fellowship with the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources.