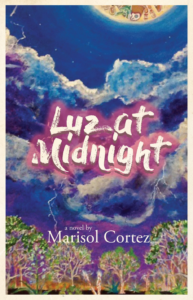

Marisol Cortez. Flowersong Press

A Corpus Christi native, Marisol Cortez moved as an infant with her family to San Antonio and grew up there and in Central Texas. She received her undergraduate degree from Texas State University and a doctorate in Cultural Studies from the University of California at Davis.

Before going off to graduate school Cortez became active in environmental justice issues in San Antonio, cutting her activist teeth fighting a Professional Golf Association plan to build a massive golf complex on land in the recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer, source of most of San Antonio’s drinking water.

After graduate school Cortez was offered a teaching position at a Kansas university and seemed destined for an academic career. But the pull of her South Texas roots occasioned a life-changing decision, and in 2012 Cortez returned to San Antonio.

“Luz at Midnight”, published last December by McAllen-based Flowersong Press, is her first novel. A contemporary love story set in South Texas during a time of climate change and a rising awareness of environmental justice issues, the novel was recently awarded the Texas Institute of Letters’ Sergio Troncoso Award for Best First Book of Fiction, the most prestigious such award in the state.

Cortez spoke with TCN deputy editor Fritz Lanham. The interview has been edited for length.

At what point did you start having literary ambitions as well as environmental commitments?

It’s more that I came back to a realization that that’s what I was primarily – a writer. At least since late middle school, early high school, I had written poetry and fiction and creative nonfiction. I majored in English, but then, when I started sending my work out trying to get it published – as a young person, of course, you get rejected. I concluded I must not be very good. I didn’t have anybody [telling] me that’s normal, just keep going. But I never stopped writing poetry, I never stopped writing fiction. I just stopped trying to make it public.

I started writing [“Luz at Midnight”] in, like, 2010, when I was in Kansas, and it just poured out. It felt it was writing me, like I wasn’t in control of this thing coming out of me. After a few years, I had a finished draft. I started feeling, if I never do anything with it, that is so much worse than putting it out there and getting rejected.

So there was a specific event or experience that prompted the book?

I would say it was just that moment of rupture in my life, a moment of crisis. Even in my mental health, where, you know, this path that I thought I was on turned out not to be the path. So yeah, it definitely came out of the unraveling of my academic trajectory – and my personal trajectory as well. The love story is pretty much autobiographical.

Let’s talk about the book’s title. Who is Luz?

Flowersong Press

She’s a dog character. She’s born in a lightning storm, apparently spontaneously generated, and the suggestion is these are intense weather events prompted by climate disruption. But she’s also a street dog, born in Brackenridge Park [in San Antonio], historically a park where people went to dump stray animals.

She’s a character who’s very cosmic. We don’t really know where she comes from, we don’t really know why she’s here. She’s a trickster kind of figure. She makes things happen at critical moments in the story. She brings characters together, she pulls other characters apart. At the same time she represents the unwanted or the excluded of city politics.

You cycle through multiple genres in the book. You do prose, poetry, drama, reportage. What was your goal in adopting that approach?

The book just came out the way it came out. The original impulse, I think, was that I know that I write in different ways. Even when I was an academic – my theory, I always wanted to have poetry in it. My poetry – always wanted to have theory in it, or it always came from a sort of theoretical impulse to explain or document things. So my natural tendency when I write is to combine genres.

In your discussion of environmental and climate-change issues, where in the book does reportage stop and fiction begin?

It’s funny because the part about the rare earth mining [a subplot involving a plan to mine rare earth minerals in South Texas and use them to manufacture wind turbines that would feed electricity to San Antonio] is stylistically some of the most nonfiction writing in the book. But that element of the story is actually the most speculative in many ways.

I knew I didn’t want to write about any one particular environmental justice struggle that I had been a part of. I felt that would be too limiting, that I would be limited to the facts of what happened in each of those struggles. I wanted, instead, to be able to write about the anatomy or the logic of all of those different struggles. So whether it was the PGA Village, or whether it was fracking in the Eagle Ford shale, or whether it was the expansion of the South Texas nuclear project, or whether it was more recent struggles around displacement and the right to remain on land within urban spaces – you saw certain dynamics happening again and again. I wanted to be able to write about those logics, but I didn’t want it to be historical fiction, per se. I felt the only way I could do that was to speculate.

There’s a passage in which you describe massive blackouts in Texas caused by a severe winter storm, and you do it in a way that anticipates with uncanny accuracy what actually happened last month. So do you have clairvoyance or what?

[Laughs] No, I don’t. I did a lot of reading about stuff that was already going on that scientists were linking to disruption. You know, we already know drought. We already know it’s getting hotter. You already know that we’re having these freeze events. That incident in particular in the book was based on something that took place in 2011. That part of the story is really just documenting what has already been happening and maybe is accelerating now. But yeah, it’s definitely weird.

Was it a challenge to find the right balance between the love story involving two people and the environmental and climate-change issues? Did you feel any stress or tension about how do I make those fit together?

Yes, I think so. And I think it’s a tension that isn’t fully resolved, ultimately, and maybe that’s OK. I worked on the love story first. That was the part of the story that felt super urgent to me. Then I went backwards from there and built the political story around it.

Fritz Lanham, TCN’s deputy editor, is an independent journalist in Houston. For 16 years he was books editor at the Houston Chronicle.