A member of the Texas National Guard helps out during Winter Storm Uri. Staff Sgt. Yvonne Ontiveros, TXARNG via flickr

Evidence of disaster lay across much of a state in shock: snow, ice, and single-digit cold. But the real proof huddled behind closed doors: millions without electricity and therefore without heat, some in grave danger, some desperately seeking warmth in their running cars only to die from carbon monoxide poisoning.

At the worst, about 4 million households, businesses, and institutions, most in the biggest metro areas, were in the cold and dark. Water failed, too, as pipes and mains burst, and treatment and pumping stations lost power. Whole cities were under boil-water orders. Some places, such as data centers, could not get diesel for backup generators.

In the language of law, what happened was a force majeure, an unpredictable, unavoidable “act of God.”

But it wasn’t. The collapse of Texas was more a result of habitual neglect, the predictable – predicted – consequence of a catastrophic failure to heed a plain warning a decade ago.

Texas went on notice in 2011, after the last polar locomotive crashed the state’s natural-gas and coal-fired power plants for days: Armor those plants and the natural-gas system against the cold, the warning went, and do it soon – because this will happen again when more severe cold snaps arrive.

“And when they do,” investigators concluded, “the cost in terms of dollars and human hardship is considerable.”

The warning came with a detailed to-do list. Texas responded by ordering more reports.

This week, it happened again.

This failure of Texas governors, lieutenant governors, House speakers, legislators, and appointed and elected regulators to act on deeply researched, nonpartisan findings – offered in hopes of curtailing future catastrophes – was not unique. It was consistent with the state’s non-response to repeated warnings about another long-term and intimately related risk.

Texas faces both a fragile electric grid, still driven mostly by fossil fuels despite renewable energy gains, and the certainty of human-induced climate disruptions caused mostly by the worldwide use of those same fossil fuels.

The two risks have converged at a historic moment – as the United States, under a new administration, restarts efforts to address climate change and, in a bigger sense, begins rethinking how we produce, use, and even imagine energy.

The Texas grid’s collapse and climate change are so linked, both in origin and perhaps in solution, that decisions about one will affect the other. In both cases, the stakes could not be higher: people’s health, safety, and welfare.

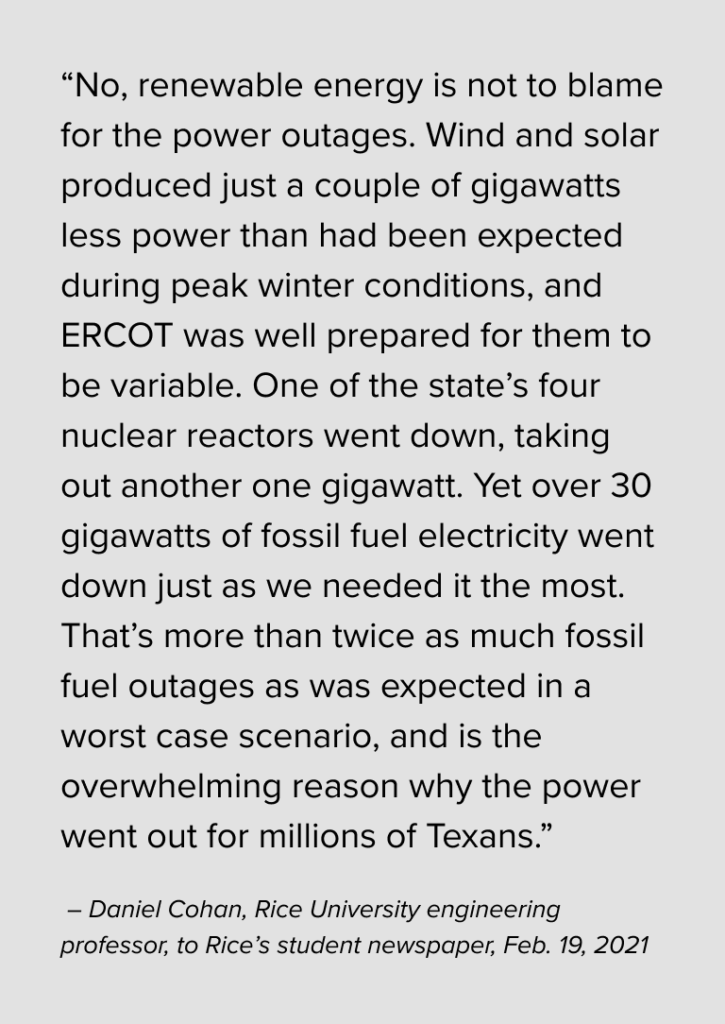

Gov. Greg Abbott claimed on Fox News that weather-related reductions in electricity from wind and solar energy were to blame for the state’s massive blackouts. Other conservative politicians and media outlets echoed that Feb. 17 allegation, particularly targeting frozen wind turbines. However, data from the state’s grid-managing agency and analyses by independent experts at Texas universities and elsewhere indicated cold weather problems at thermal energy facilities (coal, nuclear and mainly natural gas) were by far the principal reason for the power crisis. “The idea that wind is responsible for these outages is actually just absurd,” Michael Webber, an engineering professor and energy expert at the University of Texas, told the neutral fact-checking service PolitiFact, which concluded that the campaign to blame renewables was a “false narrative.” Fox News Channel screenshot

Clear failure

The National Weather Service sent out the word of approaching trouble: 3 to 8 inches of total snow accumulations in Dallas-Fort Worth. “Heavy snow and blowing snow possible,” forecasters in Fort Worth warned on Feb. 12. “Bitter cold expected and near-blizzard conditions possible. Wind chills as low as -15 degrees F.”

The grid operator for most of the state, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, predicted some increased demand as people cranked up furnaces. ERCOT said its math showed the state ready.

It wasn’t. ERCOT’s demand forecast was far too low. “The magnitude of the forecast error was massive,” consulting firm ICF told industry newsletter S&P Global Platts.

As a crisis developed, ERCOT, a nonprofit under general state oversight, announced rolling blackouts, short power cutoffs in small areas meant to spread the sacrifice. But many electricity sources – natural gas, coal and nuclear-powered plants, and wind turbines – froze and shut down or couldn’t start in the cold. The result was massive, days-long failures.

The full economic toll hasn’t been calculated, although the Austin American-Statesman reported Friday that some experts think it could break Hurricane Harvey’s $19 billion record from 2017. But other results are plain: widespread anger, bad global press for usually self-assured Texas – and obfuscation. Politicians, including Gov. Greg Abbott, went on cable news and blamed wind power failures, although data instantly proved that fossil-fuel failures were overwhelmingly at fault.

Dr. Michael K. Lindell, a nationally known expert on hazard reduction and recovery, watched the fact-free wind-scourging from Seattle, where he works at the University of Washington. But he watched with a Texas eye: He is a Texas A&M emeritus professor of urban planning.

“As a former Texas resident, I have been following the situation there with considerable interest and dismay – not to mention an utter lack of surprise at the blame heaped on the wind-generation sector,” Lindell told Texas Climate News. “The current Texas infrastructure debacle is a clear example of a failure of the hazard mitigation process.”

Some politicians, however, said the Texas calamity was too unlikely to prepare for. U.S. Rep. Dan Crenshaw, a Republican from Houston, repeated the false story that wind failures were the key. “Also,” Crenshaw tweeted on Feb. 16, “Texas infrastructure isn’t designed for once-in-a-century freezes.”

Some politicians, however, said the Texas calamity was too unlikely to prepare for. U.S. Rep. Dan Crenshaw, a Republican from Houston, repeated the false story that wind failures were the key. “Also,” Crenshaw tweeted on Feb. 16, “Texas infrastructure isn’t designed for once-in-a-century freezes.”

Crenshaw might have been right about an under-designed infrastructure, but he couldn’t have been more wrong about how often a freeze threatens the Texas grid.

It happened in 1983, 1989, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011, and 2021. The 1989 winter storm, the record until 2011, marked the first time ERCOT resorted to rolling blackouts. The 2011 storm, the record until 2021, dumped snow in huge quantities, by Texas standards, on Dallas-Fort Worth during what was to have been an exciting run-up week to Super Bowl XLV, played inside the heated, closed-roof AT&T Stadium in Arlington.

It quickly became apparent that Texas’ natural gas distribution system and its fossil-fuel power plants had failed under winter conditions normal in many other states. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC), which sets standards for much of the nation’s grid outside Texas, launched an investigation.

As the outside experts gathered reports and data, visited grid operations and power plants, and held meetings, they heard repeatedly that the degree of cold was unprecedented. They seemed unmoved. “The storm, however, was not without precedent,” they later wrote.

Many operators told investigators their plants were winterized. “However,” investigators responded, “the poor performance of many of these generating units and wells suggests that these procedures were either inadequate or were not adequately followed.”

FERC and NERC’s report, issued six months after the 2011 storm, ran to 357 pages. It laid the blame squarely on the failure, after repeated past crises, to reinforce Texas’ energy system against cold – whether with public, private, or ratepayer money, or whether by legislation, regulatory order, or voluntary action.

The report’s recommendations, mostly technical improvements used routinely in typically colder climates, were economically reasonable, investigators wrote, and “would substantially reduce the risk of blackouts and natural gas curtailments during the next extreme cold weather event that hits the Southwest.”

But by August 2011, when the report was published, official Texas had mostly moved on to other matters. Two months earlier, on June 17, then-Gov. Rick Perry had signed a bill passed in response to the February storm that instructed the Public Utility Commission to address the grid’s extreme weather plans. The state did not require actual winterization of power plants or gas equipment in 2011, or any time since.

Abbott, who became governor on Jan. 20, 2015, called for mandatory winterization on Feb. 18, 2021. “What happened is absolutely unacceptable and can never be replicated again,” the governor said.

State Rep. Rafael Anchia, a Democrat from Dallas and a member of the House Energy Resources Committee, told Texas Climate News in an email that he saw Abbott’s ignoring grid vulnerability until it made news as part of a larger problem.

“The ongoing pattern of our governor actively choosing profit over human life and the denial of global warming has highlighted the need for better leadership here in Texas,” said Anchia, who is in his eighth House term.

Serious challenges

In 2018, experts warned Texas and its Southern Plains neighbors, Oklahoma and Kansas, to expect trouble as the climate changes via human actions. It was far from the first time Texas was given that word.

“Quality of life in the region will be compromised,” the experts wrote, “as increasing population, the migration of individuals from rural to urban locations, and a changing climate redistribute demand at the intersection of food consumption, energy production, and water resources.”

That was in the Fourth National Climate Assessment, Vol. II, one of those reports, like the 2011 FERC/NERC investigation, that make headlines for a day but mark a pathway for those who pay closer attention.

The report – like Vol. I, which covered climate science and observations, and like previous reports going back years – can be tough reading, but the message is clear: Climate change is real, it’s happening, and it requires action now to get people and economies ready.

For Texas, which stretches from the Gulf of Mexico to the High Plains, and from cypress swamps to desert mountains, the range of impacts is huge – more numerous, or worse, hazards such as hurricanes, sea-level rise, droughts in some places, floods in others, shifts in agriculture, heat deaths, and strain on the electric grid, especially in brutal summers.

A handful of those risks appeared in a hazards report the state prepared in 2018, a year after Hurricane Harvey. The report covered only five years of planning and never mentioned climate change except in the footnotes. Asked about ignoring climate change’s impact, both Abbott and Texas A&M System Chancellor John Sharp, who headed the report, fell back on variations of the oft-heard “I don’t know because I’m not a scientist.”

Austin scene: Feb. 16, 2021. David Kitto via Wikimedia Commons

Sharp’s punt came despite repeated reminders by the atmospheric sciences faculty at Texas A&M itself, which includes prominent climate scientists, that “the earth’s climate is warming.” In a statement originally passed in 2014, renewed in 2019 and in effect at least through 2022, the faculty says “continued rising of atmospheric and oceanic temperatures presents the risk of serious challenges to human society and ecosystems.”

Those warnings have had little to no effect on official Texas. The state has no climate change policy, and agencies informally discourage their employees from mentioning the subject even in obviously relevant reports. For years, Democratic legislators have introduced climate-planning bills, virtually all mild measures that required little more than studies. Their nearly universal fate has been to die at the hands of committee chairs who refused to schedule hearings, as Texas Climate News reported in 2019.

The one exception was HB 2571, filed in 2015 by then-Rep. Eric Johnson. The Dallas Democrat’s bill made it to a final vote in the full House before the Republican majority defeated it. Johnson is now Dallas’ mayor.

Anchia has filed several of those failed bills. He’s trying again this session with HB 1044 (download), which would create a 25-member Texas Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission to review and improve state policies on climate and weather-related risks.

Anchia said the new commission – which he’s tried to create before – might have spotted the Texas grid’s forgotten flaws and called for fixes before millions of Texans suffered as a result. More than a month after he filed the bill, it has not been referred to a committee for hearings.

“For several years, state leaders have been in denial about the reality of climate change,” he said, “and as a result, we are all living in the consequences.”

Meanwhile, news at odds with Texas’ official attitudes toward climate change and fossil fuels seems to be breaking worldwide.

Volkswagen, General Motors, and Ford have all announced, by differing degrees, the approaching end of gasoline-powered autos. President Joe Biden has vowed to tackle climate change at home, repair ailing infrastructure to make it more tough and reliable, and place climate as “an essential element of U.S. foreign policy and national security.” Abbott called Biden’s energy plans “a hostile attack” on Texas and promised to sue.

Two noteworthy things happened Friday that may have changed the outlook. It was the first day when the United States officially rejoined the Paris Agreement on climate change.

And it was the day Texas began to thaw.

Randy Lee Loftis is the senior editor of Texas Climate News. An independent journalist in Dallas, Loftis was The Dallas Morning News’ environmental writer for 26 years. He was a founder of the Society of Environmental Journalists and is a faculty member at the University of North Texas.