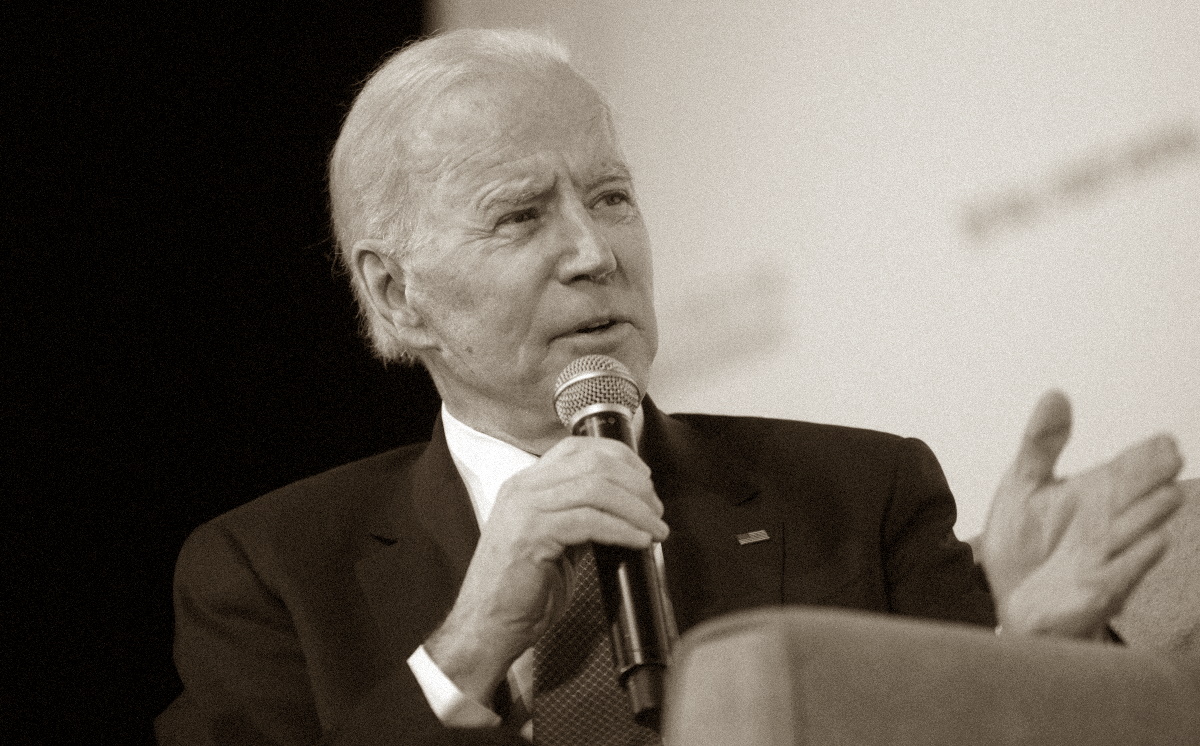

What climate platform is Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden running on? His vision of green energy jobs has brought together the factions within the party that were recently warring over climate. Or brought them together mostly … for now. Biden’s climate platform is extensive and detailed – but probably won’t matter unless Democrats take the White House, win the Senate and keep the House.

The voters on Nov. 3 face a choice. If his record to date is an accurate harbinger, re-electing Donald Trump will mean doing nothing to address climate change – and doing things that will make it worse. Electing Biden (with a willing Senate) will mean major climate action if he and fellow Democrats follow through on their campaign pledges.

Biden would have to bring a large part of his party and its allies with him in the dangerous and delicately balanced dance of legislation. And there is more than one Democratic climate agenda. But, amazingly, he has managed to bring most Democratic factions together in support of his plan.

In practice, we won’t know what either candidate will really do until we see the text of legislation and can count votes for it in both chambers of Congress. Outlines, frameworks, plans and proposals may not count.

Biden’s position

Biden’s position has evolved. Functionally, the position he will govern on, if he’s elected, will be the one unveiled July 14, a month before the Democratic National Convention.

That position, which can today be found on Biden’s campaign website, was the product of a serious dialogue with both climate activists and labor leaders. It made headlines when he picked Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York (a co-sponsor of the Green New Deal) to co-chair his climate platform task force. The product of that negotiation was much more ambitious than the platform Biden put up during the primaries. It was significant that Varshini Prakash, a leader of the Sunrise Movement that launched the Green New Deal, praised Biden’s revised position, although she added that “there’s more work to do.” For the record, Biden did not embrace the entirety of the Green New Deal, but he did call it a “crucial framework.”

Overall, Biden called for a big step-up of U.S. and global ambition in limiting climate-altering emissions from the use of fossil fuels. And like the Green New Deal – an ambitious program to fight both climate change and economic inequality – he envisions the transition to clean energy as an opportunity for creating many jobs.

A quick sketch of Biden’s current position includes the following:

- Achieving net-zero emissions for the entire U.S. economy by 2050

- Achieving an emissions-free electric power sector by 2035

- Upgrading 4 million buildings over four years to achieve the highest energy-efficiency standards

- Expanding U.S. production of clean and electric vehicles to out-compete countries like China, and financial incentives for American consumers to buy them

- Establishing an environmental and climate justice office within the Justice Department and addressing environmental justice in other ways

- Spending almost $2 trillion over four years to advance clean energy in the transportation, electricity, and building sectors

- Rejoining the Paris Climate Accord immediately upon taking office

- Aggressive use of executive and regulatory authorities to advance climate action, as seen in the Obama administration.

The other Democratic climate plans

Where it gets sticky, even if the Democrats win House, Senate and White House, will be turning all this into specific legislative language and getting the majorities needed to make law.

It may be important, even if Dems win the Senate, whether they abolish the filibuster, which often stops legislation from going through that chamber. Biden is not there yet.

It may also be important whether the Supreme Court is willing to stand by its 2007 decision in Massachusetts vs. EPA, the case that established the authority of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act. Nominee Amy Coney Barrett‘s position on that case is unknown. But she has expressed some willingness to reverse precedent, and a new, more deeply conservative majority on the Court could be tempted to revisit it.

A program as sweeping as Biden’s climate plan, or any other climate plan, will need to wend its way through many competing congressional committees. More problems stem from that.

Although Biden would effectively head the party if elected, it would still be a variegated party. Democrats for the last few years have come up with many conflicting proposals for climate.

Upon retaking the House in 2018, Speaker Nancy Pelosi set up a Select Committee on the Climate Crisis under Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Fla.). Their report fell short of the Green New Deal’s sweeping blueprint but does represent a center point for elected Democrats. Another Democratic stab at forming a climate program came from House Energy Committee Democrats, whose plan was less ambitious still. Their proposal came in the form of an actual draft bill, suggesting a grip on the practical.

Just as controversial – but perhaps less consequential – was the official platform adopted by the Democrats before their national convention in August. At the last minute, the DNC platform panel dropped a plank calling for an end to all dirty energy subsidies. The Biden campaign itself downplayed the problems this presented. But Biden’s actual position on this precise issue remains unclear.

Some grizzled veterans remember when “oil Democrats” ran much of Congress, including the House Energy Committee. The mix of climate proposals includes some that are strongly favored by the oil and gas industry – including carbon taxes and carbon capture and storage. We don’t really know how Biden would find his way through this maze.

Another pitfall Biden may (or may not) skirt is the drilling method called fracking. The combination of horizontal drilling in shale together with hydraulic fracturing has spurred the rise of gas and the decline of coal.

Environmentalists hate fracking for several reasons. Biden has declined to say he will end it (even if he had the power to do so), motivated, some think, by the need to carry Pennsylvania, where there is a lot of fracking. This has not stopped Trump (who also needs Pennsylvania) from falsely claiming that Biden opposes fracking.

Biden’s vision of climate action as a gigantic jobs program reminds us that infrastructure is not a new concept to Congress. Highway, water project, and farm bills have been an ancient tradition usually endorsed by both parties, and in recent years Dems have made them greener. The politics of pork gets these bills through in many election years. So far, this year, they seem to be mired in the partisan gridlock.

But all the current infrastructure legislation just points up how many House and Senate committees end up being involved in such major efforts – not just environmental and resource committees, but taxing and appropriations committees as well. This reality will be an obstacle for any climate program to surmount, including Biden’s. Jurisdiction, like water, is for fighting over.

So even if the Democrats take House, Senate, and White House, it may take effort to reconcile the different kinds of Democrats. An example: A Democratic Senate could well see Joe Manchin of West Virginia as chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee (not the Environment and Public Works Committee, as the original version of this article erroneously stated). The Energy Committee would surely have a major say over climate legislation – and Manchin would probably be merciful to coal, his state’s favorite fuel. Even an election-eve Trifecta win would still leave Biden’s climate visions with practical obstacles like this.

+++++

Joseph A. Davis is the Washington correspondent of Texas Climate News.