The likelihood that a tropical cyclone would become a Category 3-5 hurricane grew by 8 percent per decade between 1979 and 2017, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

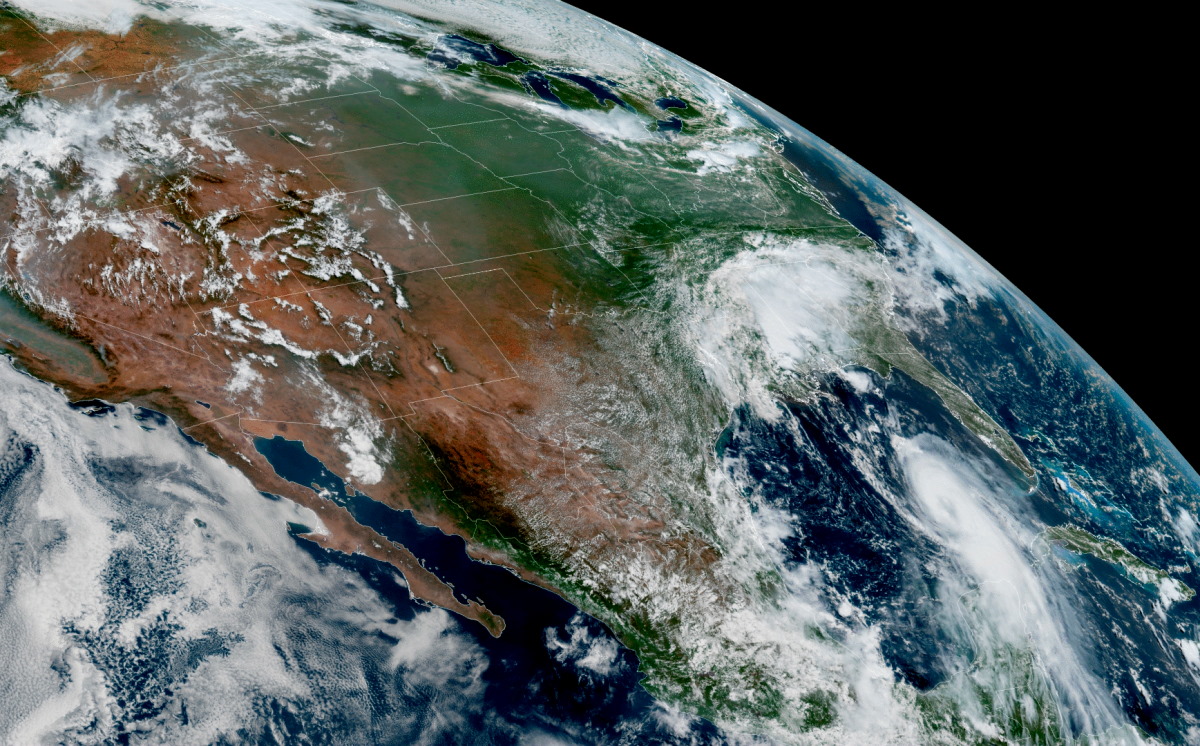

August 25, 2020: A satellite image shows the remnants of Hurricane Marco over the Southeast and Hurricane Laura in the Gulf of Mexico as it speeds toward Texas and Louisiana. To the north, smoke from wildfires in California spreads across the West and Midwest.

Hurricane Laura’s rapid strengthening into an extremely dangerous Category 4 storm with 150 mph winds at landfall offers a sobering harbinger of the effects of a warming climate on tropical cyclones.

Scientists have long predicted that manmade climate change will increase the frequency of the most powerful hurricanes, but robust evidence of an actual trend was lacking. Evidence has been growing, however, with recent studies documenting patterns of stronger, and more rapidly intensifying, storms.

In a study published in May, researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Washington reported detecting a global increase of 8 percent per decade from 1979-2017 in the likelihood that a tropical cyclone would become a major hurricane (that is, Categories 3-5 with sustained winds of 111 mph or higher).

The 39-year period was longer than a period analyzed previously, which was too short to assess statistical significance. The increased chance of a major storm that the researchers found between 1979-2017 was statistically significant and consistent with climate theory and modeling projections for a warming atmosphere, they wrote.

“We’ve just increased our confidence of our understanding of the link between hurricane intensity and climate change,” said James Kossin of NOAA and the university, lead author, upon the study’s publication in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “We have high confidence that there is a human fingerprint on these changes.”

Researchers are also reporting evidence of faster intensification of tropical cyclones.

Last year, a team of scientists from NOAA and Princeton University wrote that their study of how fast storms in the Atlantic basin strengthened from 1982-2009 had found that manmade climate warming had added to “significant increases” in intensification rates. The increases were “highly unusual” compared to model-based estimates of natural variability, they wrote.

“Tropical cyclones that rapidly intensify are typically associated with the highest forecast errors and cause a disproportionate amount of human and financial losses,” the researchers observed in the study, published in the journal Nature Communications.

Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist and climate communicator at Texas Tech University, told Texas Climate News that Laura’s rapid and extreme intensification as it neared southeastern Louisiana last week – gaining 65 mph in strength in 24 hours – was consistent with scientists’ general expectations about stronger storms in a changing climate.

Laura’s 150 mph force at landfall prompted renewed warnings in Houston about the potentially catastrophic impacts if such a powerful storm directly strikes the low-lying metropolis and its nationally crucial oil and chemical complex with devastating winds and storm surge.

Two days before Laura’s landfall, Hayhoe was a featured speaker to an online conference held by the city of Houston to discuss the climate action plan that municipal officials adopted earlier this year.

While climate scientists have not found an overall increase in hurricane frequency accompanying climate warming, she said in her presentation, storms are “intensifying faster because they get their energy from warm ocean water and the oceans are warming.”

She added, “We also see that even though the number of storms isn’t changing the percentage that are stronger is increasing, so more of the storms we have are stronger. They’re moving slower, and they’re getting bigger. None of that is good news. And then of course sea levels are rising.”

Evaluating the evidence

TCN also asked John Nielsen-Gammon, an atmospheric science professor at Texas A&M University and the Texas state climatologist, for his overview of the evolving science of hurricane intensification. His emailed reply:

On the observation side, there’s solid evidence that rapid intensification rates have increased over the past few decades in the Atlantic Ocean, where the observations are of highest quality, but that period includes a transition in phases of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation [a recurring climate cycle] that itself is not caused by global warming.

Inferences with a couple of techniques from global climate models indicate that global warming should drive an increase in rapid intensification rates, but there’s not enough modeling data for me to consider these to be robust projections.

Lastly, rapid intensification rates are different from overall frequency of occurrence of rapid intensification. The latter depends on how many storms exist in the first place, and the bulk of evidence suggests a possible decrease in overall storm frequency.

So at this point for me, it would not be surprising if global warming was causing an increase in the chance that a hurricane would intensify rapidly. Conversely, it would be surprising if global warming was causing a decrease in the chances.

Eleven climate scientists from the U.S. and other countries evaluated the persuasiveness of the overall body of research about global warming’s influence on tropical cyclone activity in a pair of papers published in 2019 and this year in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. The project revealed different levels of agreement on different points.

For instance, all 11 scientists agreed that the “balance of evidence” (showing more than a 50 percent chance) suggests there has been a “detectable increase” (compared to natural variability) in the global proportion of tropical cyclones reaching Category 4 or 5 wind speeds in recent decades. Eight of the 11 agreed that the balance of evidence suggests manmade warming “has contributed to this increase.”

On a related question, 10 of 11 saw a balance of evidence for a “detectable increase in the global average intensity” of the strongest tropical cyclones since the early 1980s. Eight of 11 agreed said the balance of evidence suggests manmade warming has added to this growing intensity.

The scientists assessed projections of future tropical storm changes in terms of their relative confidence in different statements. Overall, the tally produced a mixed picture.

Regarding storms that reach Category 4 or 5 intensity, for example, three scientists had “high” confidence their proportion of all tropical cyclones is projected to increase globally and eight scientists had “medium-to-high” confidence. There was less confidence that the frequency of Category 4 and 5 storms is projected to increase, with those ratings ranging widely “high” confidence (one scientist), “medium-to-high” (four), “medium” (one), “low-to-medium” (2) and “low” confidence (three).

Precipitation dangers

While storms like the intense but fast-moving Laura are feared mainly because of direct wind threats and wind-propelled storm surge, the influence of manmade climate change on hurricanes’ precipitation rates is another subject of keen interest, especially after Hurricane Harvey inundated wide areas of Texas.

The 11 scientists who assessed the overall body of scientific evidence about human influence expressed strong agreement on a couple of points of particular relevance to Texans and other Gulf Coast residents.

All 11 agreed the balance of evidence suggests that there already has been a “detectable long-term increase in the occurrence of Hurricane Harvey-like extreme precipitation events in the Texas region” and that manmade warming has added to that increase.

Six scientists assigned “high” confidence, and the other five gave “medium-to-high” confidence, to the future-looking statement, “Precipitation rates of tropical cyclones are projected to increase globally.”

Harvey’s catastrophic damage in the Houston region and well beyond was largely a result of it being the wettest hurricane on record in the U.S., with many areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain in the days-long deluge.

Hayhoe’s presentation to the Houston conference summarized some of the growing evidence that Harvey’s destructive precipitation was made worse by global warming:

- A 2017 study in Environmental Research Letters found global warming had made Harvey’s rainfall 15 percent more intense and made such extreme events three times more likely.

- Another study published in 2017, this one in Geophysical Research Letters, calculated that manmade climate change likely boosted the risk of Houston’s most hard-hit areas receiving so much rainfall by 3.5 times. The authors said global warming also increased the amount of precipitation there by at least 19 percent, and more likely by 38 percent.

- A study in 2018 in the journal Earth’s Future concluded that “record high ocean heat values not only increased the fuel available to sustain and intensify Harvey but also increased its flooding rains on land. Harvey could not have produced so much rain without human-induced climate change.”

- A study published in April in the journal Climate Change calculated the portion of Harvey’s economic damage (which totaled about $90 billion, averaging different assessments) was attributable to human influence on the climate system. The researchers produced a “best estimate” that $67 billion in damage (and at least $30 billion) was due to manmade warming.

With such findings about heavy precipitation in mind and with other research evidence that some strong hurricanes are “stalling” and growing more dangerous before landfall, NOAA and university scientists in March proposed a new tool to help alert the public to storms’ potential to bring havoc with heavy rainfall.

The new metric would complement the well-known Saffir-Simpson scale that ranks storms solely by wind speed (such as Laura’s Category 4) with an additional metric that the scientists called the extreme rain multiplier.

This new tool, they wrote in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, would help the public better understand an approaching storm’s potential for devastating rainfall in the context of “the magnitude of rain events that are more typically experienced in their area.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.

Katharine Hayhoe and John Nielsen-Gammon are members of TCN’s volunteer Advisory Board. Nielsen-Gammon serves solely in his capacity as regents professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University.