Above-average sea-surface temperatures could mean more powerful hurricanes this year, experts warn. Can Gulf Coast hospitals handle an influx of injured storm victims on top of a swelling Covid-19 patient load?

This photo of the impromptu shelter in Houston’s Astrodome for Hurricane Katrina evacuees in 2005 suggests how challenging any attempt to achieve infection-conscious social distancing would be in a mass hurricane evacuation during the Covid-19 pandemic. Thousands of New Orleans residents, many of whom had initially sheltered in that city’s Superdome, were evacuated to the Astrodome and other locations in Houston after Katrina flooded New Orleans.

No time is a good time for a hurricane or even a sub-hurricane cyclone, and a deadly pandemic is surely a worse time than most.

When Tropical Storm Cristobal struck the Louisiana coast on Sunday, earlier concerns about an intersection of the coronavirus and tropical weather moved from theoretical to here-and-now reality.

Cristobal’s arrival came after some slight uncertainty about whether it might drift toward Texas, so Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo held separate news briefings on storm preparation Friday.

Both Abbott and Hidalgo combined cautionary messages about Cristobal and Covid-19 in their briefings, reinforcing experts’ earlier warnings that coronavirus considerations such as maintaining social distancing in shelters and the availability of critical-care hospital beds will complicate storm planning and response during this year’s hurricane season.

A sharp spike in Covid-19 cases and hospitalizations in the Houston area last week reinforced concerns that the pandemic – especially if infections continue to increase in storm-vulnerable areas – will potentially mean even greater health and safety risks during storms.

Setting the stage for the 2020 hurricane season, which began June 1, scientists warned it could be an unusually severe one. Other researchers had cautionary messages in two studies that underscored the role of manmade climate change in heightening hurricane threats, particularly in the Gulf of Mexico.

As early as March, above-average sea-surface temperatures in the Gulf prompted warnings that warmer-than-usual sea water could intensify tropical cyclones this year. Scientists concluded that above-average temperatures amplified Hurricane Harvey’s catastrophic destructiveness in Texas in 2017.

Sea-surface temperatures in coastal waters along the Louisiana, Texas and upper Mexican coastlines continued at above-average levels in readings posted this week.

In addition to warm Gulf waters’ potential to intensify storms, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and researchers at Colorado State University have separately forecast above-average numbers of storms this year.

NOAA scientists last month forecast 13 to 19 named storms, of which six to 10 could become hurricanes (at least 74 mph winds) with three to six major hurricanes (at least 111 mph). Researchers at Colorado State, in their own yearly outlook report, forecast 19 named storms, nine hurricanes and four major hurricanes.

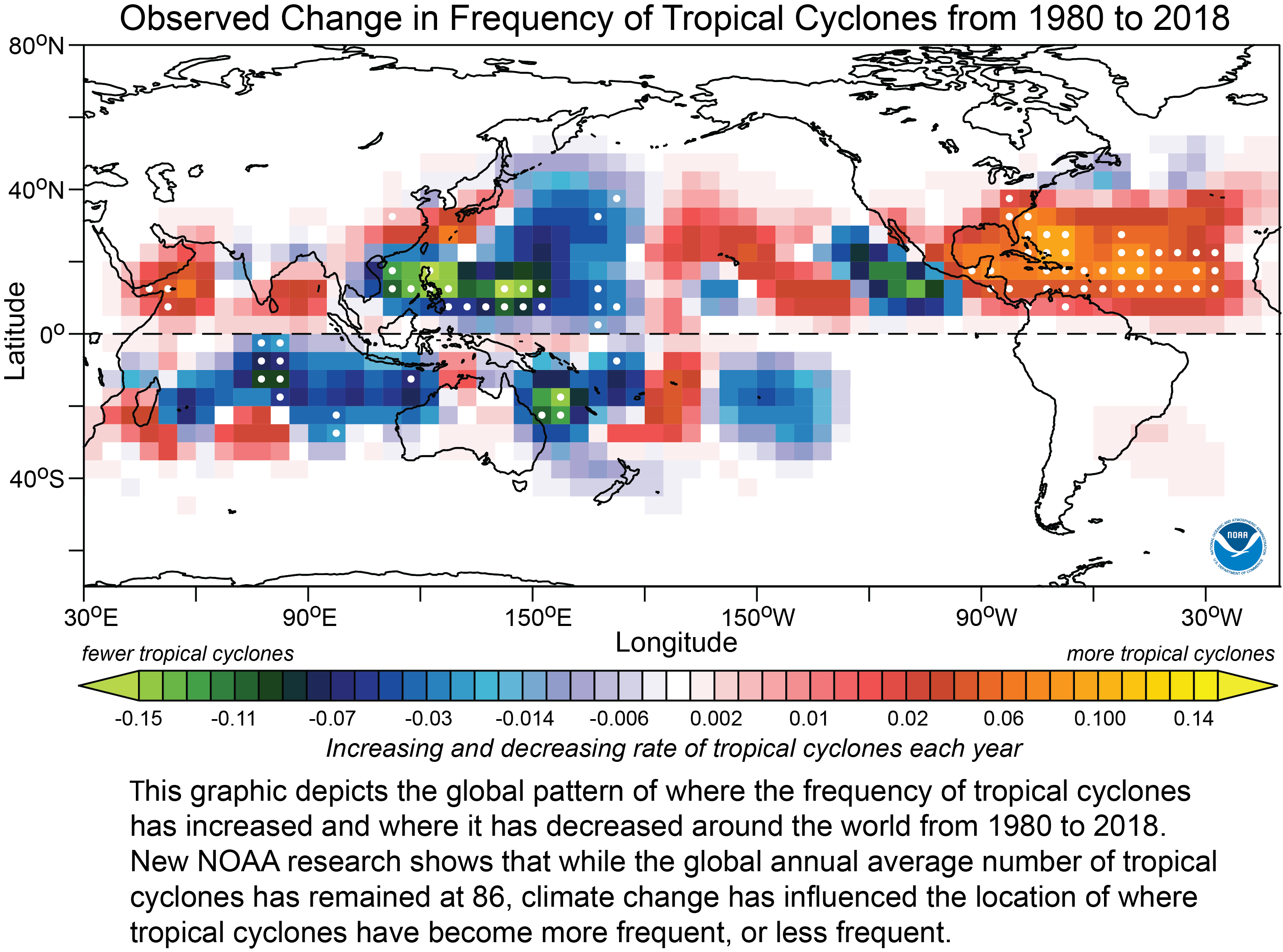

NOAA’s and Colorado State’s forecasts don’t include locations where storms might occur. However, a separate NOAA-led study, published in May, concluded that human-produced greenhouse gases have helped increase the frequency of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic, which includes the Gulf of Mexico, from 1980-2018.

Greenhouse gases, along with declining particle pollution and volcanic eruptions, have influenced increases in tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic and central Pacific and decreases in the western Pacific and southern Indian Ocean, according to the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

The researchers found that the global average number of tropical cyclones has stayed at 86 over the past four decades. Toward the end of the century, scientists have been projecting fewer but stronger tropical cyclones as a result of manmade climate change, with about 69 being the annual average.

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Another study published last month in the same journal, also led by a NOAA scientist, provided strong new evidence to support earlier research showing that global warming is producing hurricanes that are stronger and can do more damage.

The authors of this study analyzed satellite images dating back 41 years, determining that climate change has increased the worldwide chance of a hurricane reaching Category 3 status by about 8 percent every 10 years. A Category 3 hurricane is one with sustained winds of more than 110 mph.

NOAA describes a Category 3 storm on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale as one in which “devastating damage” can result: “Well-built framed homes may incur major damage or removal of roof decking and gable ends. Many trees will be snapped or uprooted, blocking numerous roads. Electricity and water will be unavailable for several days to weeks after the storm passes.”

A hurricane of any severity, or even a sub-hurricane tropical storm or depression, can stress a region’s ability to respond, and the coronavirus pandemic potentially could create conditions that would add to that stress.

One challenge could be the capacity and resilience of medical facilities that come under pressure to serve both a potentially booming population of Covid-19 patients and people injured by severe weather conditions.

Houston’s vast medical complex has held up well during the pandemic and has not been overrun with Covid-19 patients, but it’s too early to say whether last week’s surge in new cases might foretell demands larger than those that have been experienced so far by area hospitals’ intensive care facilities.

Saturday’s and Sunday’s rolling seven-day averages of new cases in Harris County (345 and 338), the heart of the Houston region, were its highest since the pandemic began, eclipsing the previous seven-day average of 325 posted on April 12.

The Houston Chronicle reported on Friday that the region’s spike in new cases had prompted Houston’s sprawling Texas Medical Center to warn that the increase in severe cases might exceed the region’s number of intensive care beds in just two weeks. A day later that estimate was changed to five weeks, which Medical Center officials called “a moderate concern.”

Statewide, Covid-19 hospitalizations are up 36 percent since Memorial Day, according to data released Tuesday by state health officials. On both Monday and Tuesday, Texas had more hospitalizations for the new coronavirus – 1,935 and 2,056, respectively – than on any day since the state’s previous high mark for hospitalizations on May 5, when hospitals received 1,888 patients.

Public health experts have warned that just such a surge in the pandemic was likely as the phased reopening of the Texas economy increased social contact. More recently, some health experts also have voiced concerns that large crowds protesting longtime Houston resident George Floyd’s killing and associated police tactics could help spread the virus. An estimated 60,000 people marched and rallied in a peaceful protest in Houston last week.

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.