As today, participants five decades ago linked environmental issues with social and economic concerns. Then, as now, public health was one subject in the spotlight – witness the attention to Covid-19 today.

An Earth Day gathering at the University of Michigan in 1970 was one of thousands across the country.

It has been 50 years since the first Earth Day was observed on April 22, 1970, with an estimated 20 million Americans participating in “teach-ins” at thousands of colleges, high schools and elementary schools, rallies, marches and other calls-to-action to understand and fight environmental degradation.

In keeping with the symbolic political stagecraft of many protests in that turbulent era, participants at some Earth Day events wore surgical and gas masks to symbolize public-health worries about the far worse air pollution of that time. Seen today, in the midst of an airborne viral pandemic, the photos from a half-century ago can seem prophetic.

Walter Cronkite told his CBS News audience in a special report that night that the participants were “predominantly young, predominantly white,” and an image of exclusivity has often stuck to the modern environmental movement that the first Earth Day helped launch.

In many ways, charges that environmental concern is the province of an affluent elite, to the extent that they still have any traction in today’s political arena, seem simplistic and unfair in light of numerous developments over the past half-century.

Since the initial Earth Day in 1970, environmentalists have a long record of acknowledging and acting to remedy a shortage of economic and ethnic diversity in their movement. With much public soul-searching, they have worked to highlight the ways that pollution and climate change and other environmental woes disproportionately affect people of color and poor and working class communities.

At the same time, movements for “environmental justice” and “climate justice” have grown among minority and less-affluent groups. Polls have found, in fact, that environmental causes often earn the strongest support from those segments of the American population.

This is not a particularly new phenomenon. As early as 2008, researchers at Yale and George Mason universities detected it in a national opinion survey that they jointly conducted:

Hispanics, African Americans and people of other races and ethnicities were often the strongest supporters of climate and energy policies [to counter climate change] and were also more likely to support these policies even if they incurred greater costs.

The finding came as no surprise to the researchers, who wrote in a 2010 report:

The impacts of climate change are likely to be felt disproportionately by those who face socioeconomic inequalities. In the United States this includes many Hispanics, African Americans and other racial and ethnic groups who are likely to be more vulnerable to heat waves, extreme weather events, environmental degradation, and subsequent labor market dislocations.

Forty years before that report, on the first Earth Day connections were being explicitly and forcefully drawn between environmental issues and broader social and economic concerns.

One person to do so was Gaylord Nelson, a U.S. senator from Wisconsin, who had conceived Earth Day as an April event to educate about, call attention to, and organize for political and personal action against environmental problems.

In a Denver speech on April 22, 1970, one of hundreds of Earth Day observances around the country on that date and other days during the month, Nelson made clear that he didn’t want the event he had thought up to be just about reducing pollution and natural conservation.

Unmistakable echoes of his remarks on that first Earth Day can be discerned in the environmental justice movement of later years and proposals today for a Green New Deal to fight climate change while creating new jobs. Here’s part of what Nelson told his Denver audience:

Earth Day can – and it must – lend a new urgency and a new support to solving the problems that still threaten to tear the fabric of this society, the problems of race, of war, of poverty, of modern-day institutions.

Ecology is a big science, a big concept – not a copout. It is concerned with the total ecosystem – not just with how we dispose of our tin cans, bottles and sewage.

Environment is all of America and its problems. It is rats in the ghetto. It is a hungry child in a land of affluence. It is housing that is not worthy of the name, neighborhoods not fit to inhabit.

[…]

Our goal is not just an environment of clean air and water and scenic beauty. The objective is an environment of decency, quality and mutual respect for all other human beings and all other living creatures.

Just as Nelson sought to link environmental concerns to 1970’s debates about race, war and poverty, some of this year’s Earth Day participants have been highlighting linkages between environmental and other issues – particularly public health, and even more especially, the Covid-19 pandemic that dominates global worry and attention.

Earth Day Network, a nonprofit long chaired by Denis Hayes, who organized the first Earth Day when he was a graduate student, has been drawing attention, for example, to the connections between deforestation, climate change and the unleashing of animal-to-human diseases like the new coronavirus.

In keeping with this year’s socially distanced Earth Day celebration, activities that had been planned as massive outdoor gatherings, many aimed at building on recent momentum for climate action, are being held online instead. Dallas’ EarthX, for instance, which bills itself as “the world’s largest environmental experience,” is offering virtual conferences and events and an online film festival in place of its originally planned gatherings at the city’s Fair Park.

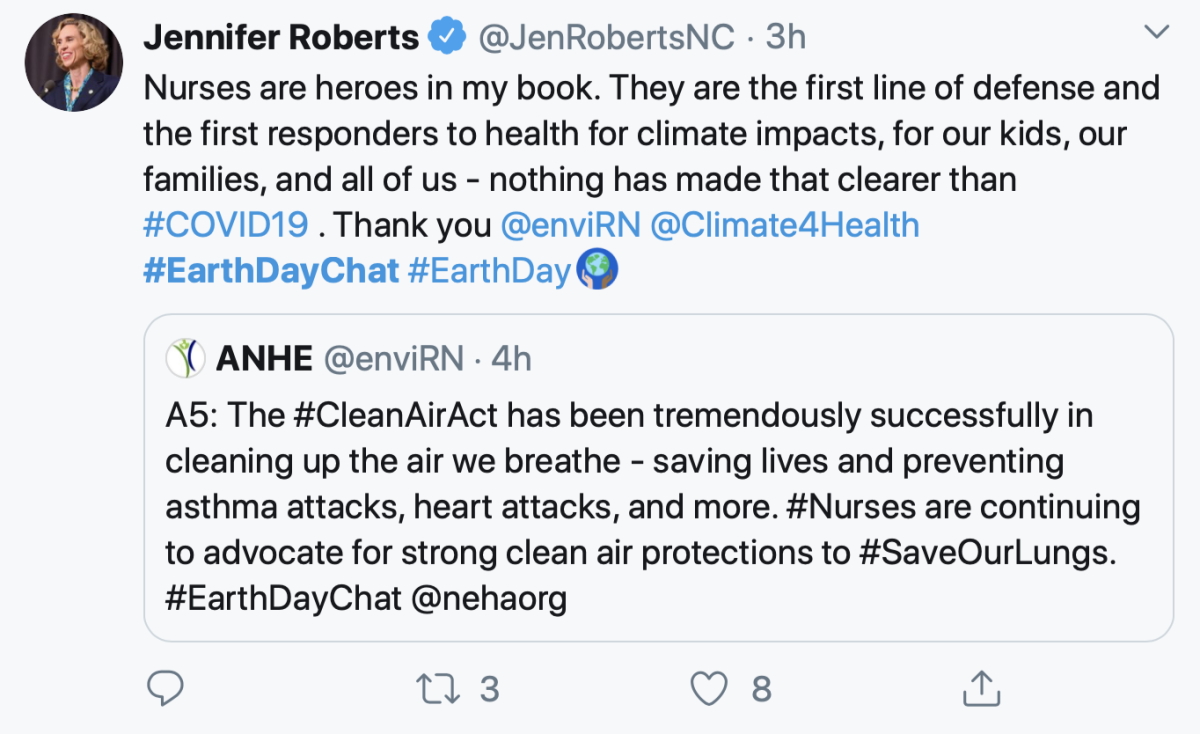

Among other virtual observances, the National Environmental Health Association staged an #EarthDayChat on Twitter this week, posing a number of questions about environment-health connections to spur discussion.

In one exchange, the former mayor of Charlotte, N.C., Jennifer Roberts, replied to a tweet from the Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments:

The Children’s Environmental Health Network explained one connection between climate change and Covid-19:

And in the spirit of professorial lectures and panel discussions at the first Earth Day’s teach-ins, Harvard University’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment drew attention to a Q&A on its website by its director, “Coronavirus, Climate Change and the Environment:”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.