Calpine natural gas power plant near Richmond in Southeast Texas

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

Many energy experts see coal-fired electricity production, a major source of climate-changing pollution, as a dying industry. Even so, top Republican officials in Texas have been trying their best since the mid-2000s to bolster coal’s status.

Despite their efforts and the allied work of other coal boosters, notably including Donald Trump since he moved into the White House, coal’s decline has persisted in the U.S.

One recent indication that the downward trend for coal is continuing in Texas came in a report by ERCOT, the agency that manages the electric grid throughout most of the state.

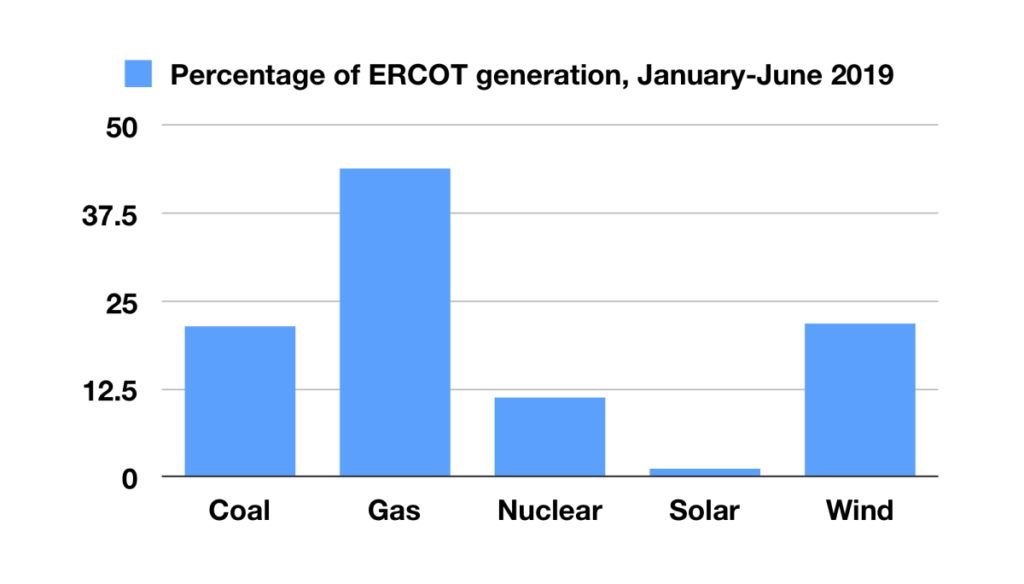

For the first time since ERCOT started tracking changes in its region’s power-production mix in 2003, Texas’ growing and nation-leading wind industry outpaced coal generation in electricity production – by just a smidgen – in the first six months of this year.

Natural gas continued to be the ERCOT region’s leading source of electricity with 43.97 percent of the total. Wind produced 21.78 percent, coal 21.37 percent, nuclear 11.35 percent and solar 1.12 percent, with other sources making up the small remainder.

Data: ERCOT

Coal’s slide at the expense of clean renewables and natural gas (pitched as the cleanest of the fossil fuels but fraught with controversy over its own climate-changing potential) has continued at U.S. locations beyond Texas.

Headwinds for coal nationally

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) announced in June that electricity from renewables (utility-scale hydro, wind, solar, geothermal and biomass) had exceeded coal-produced power nationwide for the first time in April. Renewables accounted for 23 percent versus coal’s 20 percent.

“This outcome reflects both seasonal factors as well as long-term increases in renewable generation and decreases in coal generation,” the agency said.

“Record generation from wind and near-record generation from solar contributed to the overall rise in renewable electricity generation this spring. Electricity generation from wind and solar has increased as more generating capacity has been installed.”

The EIA announced in December that coal consumption across the nation had declined to its lowest point in 39 years, despite a growing population and economy. U.S. coal use had grown until about 10 years ago.

Former Gov. Rick Perry, now Trump’s energy secretary in Washington, has a long record of trying to prop up the declining coal industry, both in Texas and nationally.

As governor, Perry failed to win court approval for a plan to “fast-track” state environmental permits for 11 new coal-burning power plants in Texas. New owners that bought the company behind the proposal canceled the eight plants that were opposed by a coalition of Texas cities, founded by Houston and Dallas, which had cited concerns about the plants’ smog-forming and climate-altering threat. Since that time, plans for other proposed plants were abandoned, and a number of operating plants were closed.

The Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, an effort in recent years to stop construction of new coal plants and advocate the closure of others, currently lists 12 operating or partially retired coal plants in Texas. The campaign had targeted another 20 once-proposed plants in the state that it now lists as “defeated.” (The Houston Chronicle last month reported that one of the state’s operating coal plants, near Bryan, would be closing in October.)

Perry has also tried, but so far has failed, in a bid as secretary of the Department of Energy to arrange a bailout, in the form of a cost-recovery program, for older coal and nuclear plants at risk of closing.

The effort had appeared to be dead, but reports in the spring indicated Perry and the White House might give the bailout idea another try. He told an energy conference in Houston the Trump administration had not abandoned the effort but also urged that states craft programs to keep old coal and nuclear plants operating. Ohio lawmakers did just that last month, passing a law to bail out two coal plants and two nuclear plants and gut the state’s standards for renewable energy and energy efficiency.

As in Perry’s push, issues surrounding the reliability of the electric power grid and renewables’ asserted role in jeopardizing that reliability figured in a recent battle at the Texas Legislature.

A failed anti-wind bid in the Legislature

Leading up to and including the 2019 session, a months-long effort by the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation attacked the wind industry and sought to persuade state lawmakers to end property-tax breaks that have boosted the growth of renewables, especially wind energy, in Texas.

The campaign by the foundation – an influential fossil-fuel supporter and critic of concerns about climate change – was not framed specifically as an effort to help coal compete more effectively in the Texas electricity market but might have had that effect if it had succeeded, along with helping natural gas.

It was a pricey project. The Austin American-Statesman reported that the foundation, enjoying annual revenue near $20 million, employed more than 20 staff members as lobbyists during this year’s legislative session, “paying them as much as $395,000, to target renewable energy subsidies, among a range of bills that align with the group’s small government focus.”

The American-Statesman offered details of the foundation’s “deep ties with fossil fuels,” including the influential and controversial Koch brothers’ Koch Industries (involved in oil and petrochemicals) and Koch family foundations, but the foundation refused to discuss sources of its donations with the newspaper.

Whoever paid for it, the foundation’s anti-renewables drive failed. Two key losses during the legislative session for the anti-wind effort stand out: A pair of bills targeting federal tax incentives used for wind and solar projects both died in committee. And legislators extended for 10 years an expiring state property-tax abatement program that also benefits renewables projects.

Trump’s big coal-friendly move

Coal and its friends did score a major and expected victory in June when the Trump administration finalized its replacement of Barack Obama’s coal-diminishing Clean Power Plan with a replacement set of regulations, much friendlier to the coal industry, called the Affordable Clean Energy rule.

Those friends of coal and of the Trump plan included the state of Texas, which had joined a coalition of states suing to block the Clean Power Plan. The now-replaced Obama regulations would have compelled states to devise plans to reduce climate-disrupting greenhouse pollution in the production of electricity. The requirement was designed to result in replacement of most coal-fired electricity with renewables, natural gas and efficiency measures, with different mixes in different states.

The New York Times’ summary of Trump’s replacement called it the president’s “most direct effort to protect the coal industry” and said it “would keep [coal] plants open longer and undercut progress on reducing carbon emissions” while largely affording states “the authority to decide how far to scale back emissions, or not to do it at all, and significantly reduces the federal government’s role in setting standards.”

The regulatory swap could delay closure of some aging coal plants but may not make a fundamental difference in Texas, however.

While the Obama plan was hung up in the courts, Texas refused even to begin work (as some states did) on the rules to comply with the plan’s mandate for an emission-reducing transition in electricity production. Even so, as the ERCOT report showed – and coal’s critics and competitors have been predicting – market forces have been hastening coal’s replacement by Texas-produced natural gas and wind energy in Texas anyway, without the Clean Power Plan’s added regulatory impetus.

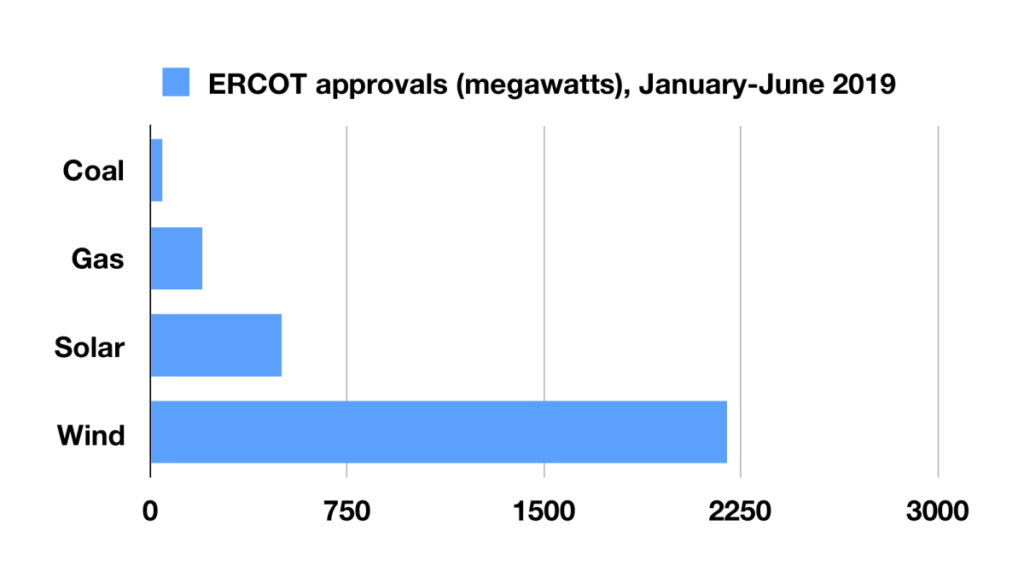

Renewables dominant in 2019 ERCOT approvals

That trend is continuing, according to an analysis by Texas Climate News of ERCOT’s recent actions on power producers’ applications to add electric-generating capacity to the grid the agency manages.

In the first six months of this year, renewables (especially wind) overwhelmingly dominated those approved applications. Interim or final approval was granted to wind projects totaling 2,198 megawatts, solar projects totaling 500 megawatts, natural gas projects adding 196 megawatts, and one coal plant adding 45 megawatts.

Data: ERCOT

Nearly a fourth of the natural gas addition (45 megawatts) and all of the coal addition (45 megawatts) were older plants coming back online. Only six of 2,198 wind megawatts and none of the solar energy represented repowering of older facilities.

Among other factors behind these trends, Felix Mormann, a law professor at Texas A&M University, told Houston’s NPR affiliate KUHF last year, natural gas is a better fit than coal with renewables’ inherently intermittent production:

“Natural gas-fired power plants have the ability to reduce and increase their output very quickly, and that’s what’s required in a grid where we have a lot of output coming from solar and wind that depends on weather conditions.”

Critics of renewables continue to press the argument that battery-storage technology is not yet advanced enough to offset wind and solar variability, which they say increases chances for electricity shortfalls like rolling blackouts without on-demand fossil-fuel generation.

Researchers at Houston’s Rice University, however, published a study earlier this year in which they concluded that by coordinating wind and solar output at different times of day and in different parts of Texas, grid operators could replace coal completely as a source of electricity in the state while offsetting the renewable sources’ variability.

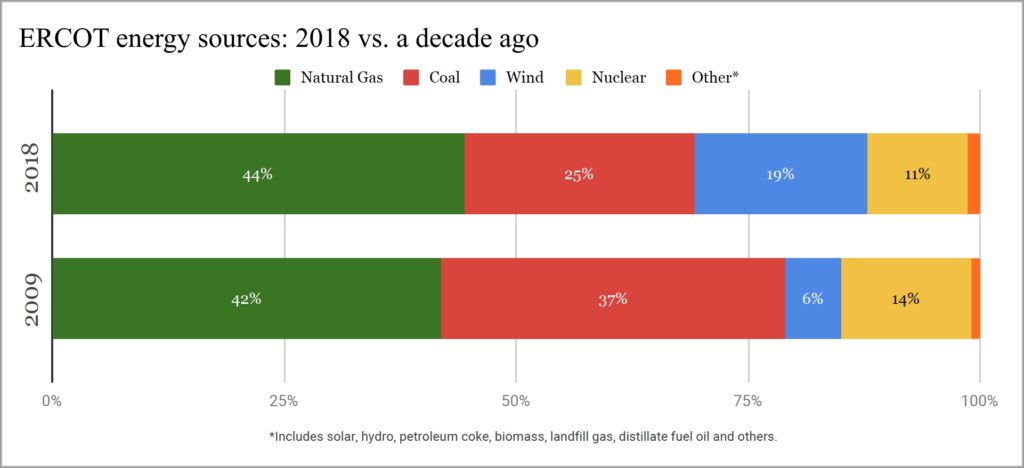

Coal, the biggest emitter of climate-warming CO2 among the major electricity sources in the ERCOT region of Texas, has declined while wind power has increased. (Data: ERCOT)

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founder and editor of Texas Climate News