By Kelly Calagna

By Kelly Calagna

Texas Climate News

From barbecue to boots, cattle have been a cornerstone of Texas culture, history and identity since the Lone Star State pioneered American beef production in the 1800s. So it’s understandable that some Texans feel personally attacked when blame strikes the cattle industry for its sizable greenhouse-gas emissions – because in Texas, cows are personal.

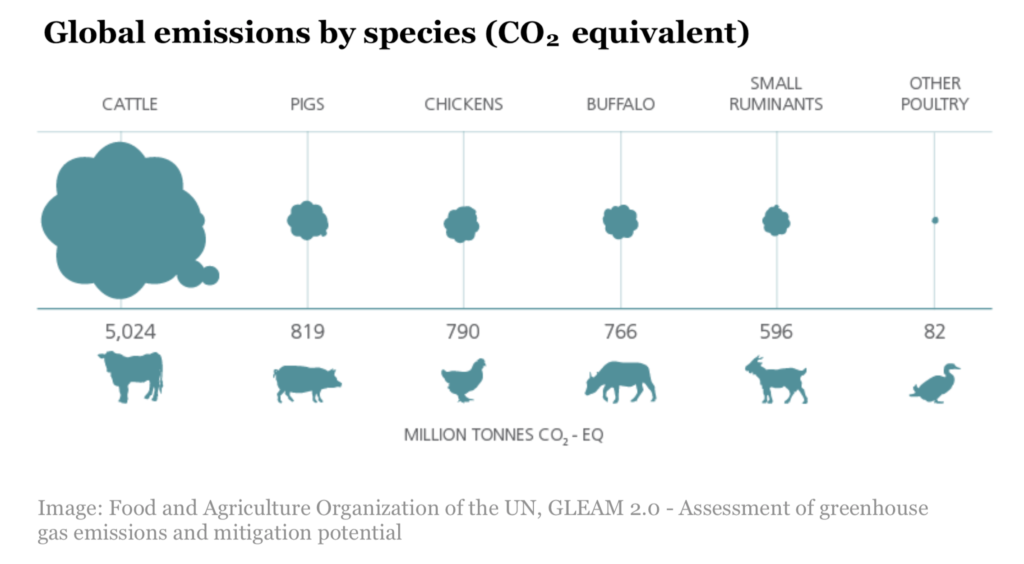

It’s a hard truth that livestock, mostly cattle, produce over a third of the U.S.’s emissions of methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas with an estimated 34 times greater warming effect than CO2. Despite the planetary impact, however, some people are not willing to give up their hamburgers.

Switching to a vegan or vegetarian diet has been shown to significantly reduce an individual’s carbon footprint, but it is not a feasible solution to the problem. Beyond the diehard burger-lover, people all over the globe rely on cattle for income and sustenance, and in some poorer regions there are often no viable alternatives. Farming livestock, mostly cattle, provides a living for about 59 percent of the poor people living in rural and marginal communities and offers poor farmers increased economic stability and opportunity.

The bottom line is that people are not ready to transition to sustaining themselves without carbon-intensive animal products. Luckily, scientists around the globe are aggressively working on ways to make cattle and other ruminants, such as sheep and goats, more sustainable in the near future.

Cattle are methane machines

Ruminants are grazing mammals that use multi-chamber stomachs to digest large quantities of foliage through a fermentation process involving microorganisms, called enteric fermentation. The microbial activity in the animal’s stomach is crucial for it to be able to break down complex carbohydrates and utilize them. Without help from the microbes, ruminants would not be able to sustain themselves on their rough foliage diets and would not have been able to become the 200-plus successful species thriving on Earth today.

However, it is also this magical microbial process that makes ruminants so greenhouse-gassy. Enteric fermentation causes these animals to belch up significant amounts of methane emissions as the microbes in their rumen break down their food. As much as 12 percent of an animal’s energy can be lost during this digestion process, requiring cattle to consume more energy than they utilize.

About 30 percent of global anthropogenic methane emissions are produced by ruminants, mostly cattle. Over the past 250 years, as humans bred more animals, ate more meat and developed large-scale ranching operations, the concentration of CH4 in the atmosphere has increased by 164 percent, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This is especially concerning because methane holds significantly more heat in the atmosphere than CO2, trapping 84 times more than CO2 over the first 20 years after it is released into the air.

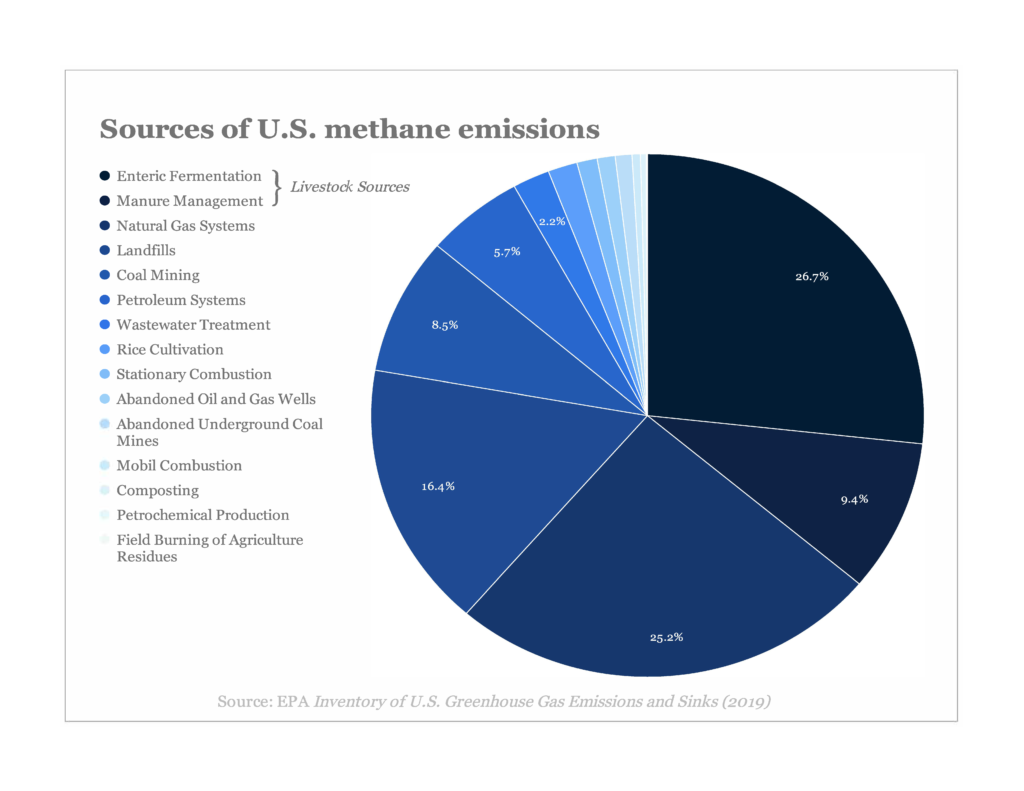

A recent EPA report found that methane accounted for about 10.2 percent of the United States’ total greenhouse gas emissions in 2017. Additionally, of all of the anthropogenic sources of CH4 over a third of the methane produced by the U.S. is attributed to livestock, with enteric fermentation and manure management accounting for 26.7 and 9.4 percent, respectively.

The report states that enteric fermentation has increased by about 6.9 percent from 1990 to 2017, which generally follows the rising trends in cattle population. This year, the number of cattle in the U.S. reached its highest point in the last decade, with Texas home to the most cattle by far – at 13 million head.

Making a high-efficiency cow

Reducing cattle populations is just part of the solution. Reducing ruminant livestock emissions is a complex global issue, requiring solutions with the dexterity to transcend geographic locations and socioeconomic systems. Mitigation depends on decreasing the number of animals while also increasing the efficiency and productivity of the individual animal.

Between 2 percent and 12 percent of a ruminant’s energy is lost through the process of enteric fermentation. In addition to cutting the animal’s GHG emissions, making a cow’s digestive process more efficient would reduce the amount of food required per animal, saving resources and offering producers a better bottom line.

Texas microbiologist Elizabeth Latham, co-founder of Bryan-based Bezoar Laboratories, is one of the scientists tackling the challenge of making a high-efficiency cow.

“I see climate change as a symptom to a bigger problem, which is either a misuse of resources or a lack of optimization/efficiency, and in terms of enteric methane, that represents a metabolic inefficiency,” Latham said.

It is this metabolic inefficiency that Latham set out to address as a Ph.D. candidate at Texas A&M University, where she began the development of a methane-reducing probiotic for cattle. In 2017, Latham co-founded Bezoar Laboratories with the goal of increasing the health and sustainability of the meat and dairy industries.

The probiotic, called Paenibacillus fortis, can be easily eaten by cattle, so it works in their rumen to block the processes that produce methane.

“You can think of it like carbon trapping,” Latham said, “because the [greenhouse gas] that would have been lost to the atmosphere can now be used metabolically by the animal, so that translates to more meat or more milk, or feeding them less.”

The cost-efficient probiotic has been shown to reduce enteric methane by up to 50 percent per animal, while also reducing common food-borne pathogens, such as e. coli, campylobacter and salmonella, by 300 percent. Paenibacillus fortis is now patent-pending and being tested for a pilot program that could begin at select dairy farms as early as next year.

“This is something that we kind of needed 5 years ago – or even sooner. I mean, 20 years ago we could have used something like this because sustainability has always been an issue for as long as human beings have been having as large of an impact as we are on the planet,” Latham said. “Really the sooner the better.”

As of today, 186 parties have ratified the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, pledging to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and to support efforts for developing new avenues for mitigating climate change. Although President Trump announced in 2017 that the U.S. would be withdrawing from the agreement by late 2020, 23 states and Puerto Rico have come together to form the U.S. Climate Alliance, committing to the agreement’s objectives. In one form or another, countries, cities, businesses and individuals around the globe are forging programs and partnerships to address the many threats to our climate, including enteric fermentation.

In New Zealand, where recent data indicate that sheep outnumber human citizens by 5.5 to 1, the government has dedicated the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre’s Methane Research Programme (NZAGRC) to researching advanced ways to reduce enteric methane production. The program is experimenting with genetic and genomic selection technologies to breed low-emission sheep, methane inhibiters that can be used in ruminants’ digestive systems and a vaccine that targets methanogen, a methane-producing bacterium within rumen.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has partnered with the New Zealand research effort to develop additional projects in low- and middle-income nations. Researchers in South America, Africa and Asia are exploring ways to improve the quality and sustainability of animal feed by improving grazing and grassland management. These and other methods can optimize food digestibility, reducing resources required per animal and increasing profits for producers.

“Even if you don’t care about climate change, nobody can deny that efficiency is a good thing,” Latham said. “And efficiency, the vast majority of the time, is going to lead to environmental sustainability.”

+++++

Kelly Calagna is a contributing editor for Texas Climate News. She is an independent journalist based in Houston, covering topics related to climate, science and the environment.