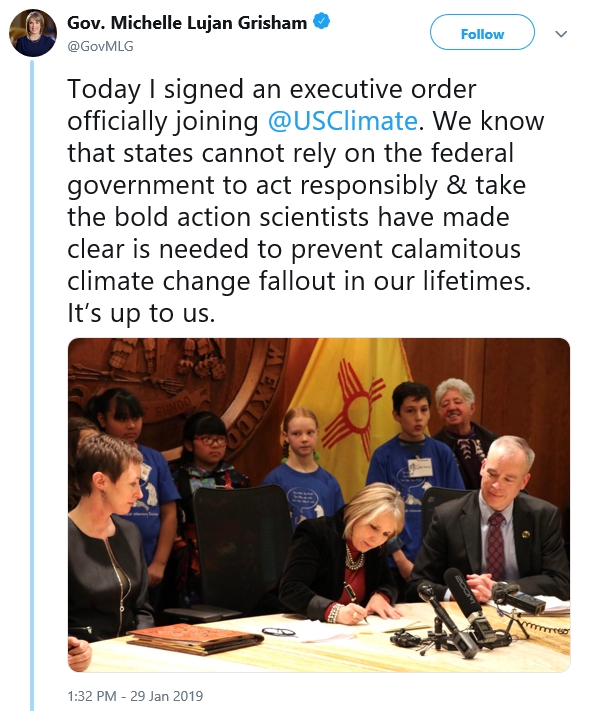

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham tweeted news of her executive order adding that state to the U.S. Climate Alliance. Members commit to cut greenhouse emissions and uphold the Paris Climate Agreement.

Texas Climate News is unmistakably and resolutely Texas-centric. Texas is the first word in our name, after all.

We also pay attention to goings-on beyond the state’s borders, of course, especially in our two sections at the bottom of the home page – Reports by Others, with complete articles, and On Other Sites, with linked headlines.

This article marks our introduction of a new, occasional offering – articles of our own, tagged “Elsewhere” – in which we present our selection of annotated and linked examples of climate-related actions and other news beyond Texas.

Most will focus on actions to acknowledge climate science and to fight and adapt to climate change. Many will represent contrasts to the action-averse records of many Texas leaders.

Even with an abundance of digital tools to keep up with news about climate change, we know it can sometimes be tough to do so. We hope our “Elsewhere” articles will help, while complementing our continuing concentration on Texas.

In this first installment, we outline recent state-government (and related) developments in several places. – Bill Dawson

New Mexico

New Mexico shares a number of features with adjoining West Texas – notably, for climate and other environmental considerations, a booming oil and gas industry.

In dramatic contrast to Texas, however, New Mexico now has official targets for cutting greenhouse-gas emissions – including those from oil and gas production.

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham issued an executive order last week laying out an array of actions. They include developing new regulations on climate-disrupting methane from oil and gas operations, encouraging renewable energy and improving energy efficiency.

Lujan Grisham, a Democrat, also said she would convene a climate change task force to devise a sweeping strategy for fighting climate change throughout New Mexico’s economy.

Texas has never launched such a state-level effort. In fact, a gubernatorial commission that studied how to protect against hurricanes like Harvey omitted any explicit reference to man-made climate change, which scientists say made Harvey more destructive.

Florida

Ron DeSantis, Florida’s new Republican governor, didn’t leave a record in Congress that gave climate-action advocates and other environmentally concerned voters much hope when he was elected last fall to head the state government.

From 2013-17, the national League of Conservation Voters gave DeSantis a “lifetime score” of just two percent, meaning he had cast what the group deemed 167 “anti-environment” votes and four “pro-environment” votes on 171 selected House actions.

In just a few weeks as governor, however, DeSantis has issued directives “aimed at cleaning up water and helping Florida adapt to the effects of global warming, including more intense hurricanes and sea level rise that threatens to swallow parts of the state in the coming decades,” InsideClimate News reported.

Though he hasn’t moved to limit greenhouse emissions, as Lujan Grisham did, DeSantis said he would appoint a “chief science officer,” encouraging some climate advocates to think he is “at least willing to listen to scientists on environmental and climate issues,” which would be “a sharp turn from the last eight years under the administration of Republican Rick Scott,” who was elected to the Senate in November.

North Carolina

Climate science – particularly studies linking climate change to stronger hurricanes – was clearly on North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper’s mind last fall when the Democrat committed his state to reduce greenhouse gases by certain percentages, as Lujan Grisham later did.

The Charlotte Observer reported that “Cooper prefaced his announcement by saying that powerful hurricanes and other consequences of climate change are forcing government to respond. He noted that Hurricane Florence, which soaked the state last month, was the third 500-year flooding event in the state in the past 19 years and the second in the past 23 months.”

InsideClimate News, reporting on Cooper’s action, noted that he “also instructed state agencies to incorporate climate science into their decision-making, a shift for a state where lawmakers just six years ago passed legislation to prevent North Carolina officials from basing coastal policies on projections of sea level rise.”

Michigan, Pennsylvania, Illinois

The announcements in New Mexico and North Carolina were connected to those governors’ decisions to join a bipartisan compact of states called the U.S. Climate Alliance.

On Feb. 4 Michigan became the latest state to join the group, whose members commit to implement policies to advance the Paris Climate Agreement’s emission-cutting agenda. Donald Trump is in the process of removing the U.S. from the agreement.

The governors of Pennsylvania and Illinois announced in January that they were joining the alliance, which now has 20 member states, mainly led by Democratic governors, collectively representing nearly half of the U.S. economy. (It probably goes without saying, Texas is not a member.)

Member states also commit to “accelerate new and existing policies to reduce carbon pollution and promote clean energy deployment at the state and federal level.”

But executive orders by governors can only go so far. Pennsylvania’s Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf acknowledged as much last month, noting that legislative action to meet his emission goals was not likely. Both houses of Pennsylvania’s legislature are in Republican hands.

Arkansas

Arkansas, another Texas neighbor and one of the reddest of states in the 2016 presidential election, is also Republican-controlled. The governor and lieutenant governor are Republicans, while that party holds essentially three-to-one margins in both houses of the General Assembly (26-9 in the Senate and 76-24 in the House).

Republicans, based on consistent polling in recent years, aren’t as likely to accept climate science or support climate action as Democrats and Independents. But polls show things are changing in that regard, and a recent opinion survey by the University of Arkansas’ respected Arkansas Poll suggested the state could be one more example of that trend.

Responses weren’t broken down according to political party. Whether they foretell greater political support for climate action in the state is anyone’s guess, but the results did capture a dramatic recent shift in Arkansans’ attitudes.

The university announced the finding last November:

“For the past four years, the Arkansas poll asked: ‘Do you think global warming, or climate change, will pose a serious threat to you or your way of life in your lifetime?’ This year, the number of people who answered ‘yes’ increased by more than 50 percent, from 30 percent to 47 percent. Forty-four percent of respondents answered ‘no,’ a decrease of 17 points from last year.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is Texas Climate News’ founding editor.