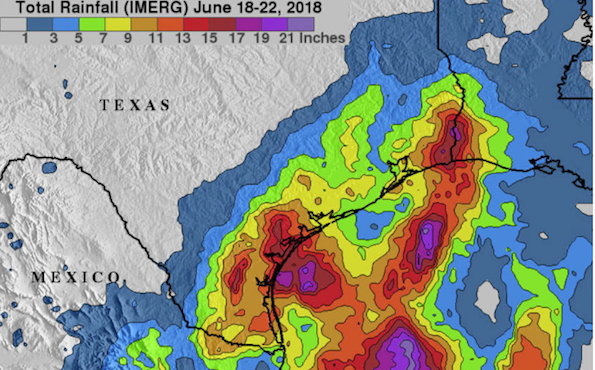

NASA’s rainfall estimates for June 18-22

By Bill Dawson and Ruth Sorelle

Texas Climate News

Texans have suffered repeatedly from flooding when slow-moving storm systems from the Gulf stalled instead of passing through rapidly. That happened in Tropical Storm Allison in 2001, Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and an unnamed tropical disturbance last month.

More such inundations appear to lie ahead as global warming progresses, according to a new study published in the journal Nature. The author, a federal scientist, calculated that as heat-trapping pollution warmed the planet by about 0.5 degree C, tropical cyclones slowed down worldwide by an average 10 percent from 1949-2016.

Scientists already have been warning that a warming climate is causing tropical cyclones (weather systems called disturbances, storms or hurricanes, depending on their strength) to carry more water vapor – and therefore pose greater flooding risks.

The study author, James P. Kossin of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, concluded that the slowdown in tropical cyclones he discovered had “very likely” boosted rainfall totals increased by higher temperatures.

A 10-percent slowdown in a storm’s pace could double the local rainfall and flooding caused by an average global temperature increase of 1 degree Celsius, he said.

Ten percent was the global average slowdown rate that Kossin calculated has occurred. Rate changes varied in different oceans. There was a 20-percent slowdown in the North Atlantic, which includes the Gulf of Mexico.

“These trends are almost certainly increasing local rainfall totals and freshwater flooding, which is associated with very high mortality risk,” Kossin wrote.

Hurricane Harvey’s “stall” over the Texas coast, which led to catastrophic flooding from rainfall of up to 50 inches, was “a notable example” of the relationship between local rainfall and a tropical cyclone’s speed of movement, he added.

Scientists generally expect global warming to change atmospheric circulations, including a weakening of the circulation that propels tropical cyclones. Still, “more study is needed to determine how much more slowing [of tropical cyclones] will occur with continued warming,” Kossin said.

Slow storms and Texas

Slow-moving Gulf storms have had significant impacts in Texas during the last two decades.

Allison lingered near Houston, flooding 70,000 homes and severely damaging major structures in the city’s downtown and Texas Medical Center areas. The storm killed 23 in Texas.

Far worse were the devastating floods from the laggardly Harvey – “the hurricane that refused to leave,” as one federal assessment dubbed it. More than 200,000 homes and businesses were destroyed or damaged in the record-setting deluge, while 89 lives were lost.

Last month, a tropical disturbance that wasn’t strong enough to qualify as a storm or hurricane “sat in place for almost a week” over Southeast Texas. Inching along, it brought flooding to locations along the entire Texas coast – the state’s worst flooding since Harvey. The impact was especially severe in Rio Grande Valley cities such as Harlingen, where the local newspaper reported “a shocking 72-hour rainfall total of 14.65 inches.”

NASA used information gathered in its IMERG project to create a space-based estimate of rainfall amounts over Texas and neighboring areas from June 18-22, pictured above.

“IMERG estimates showed extremely heavy precipitation fell over southern Texas and the northwestern Gulf of Mexico,” NASA said. “[They] indicated that the heaviest rainfall occurred in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico where over 21 inches of rain fell. IMERG data also indicated that more than 9 inches fell in large areas from south Texas to western Louisiana.”

Public-health implications

On June 19, while that weather system was lingering in place, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention marked the start of the 2018 hurricane season with a webinar briefing for journalists on the public-health hazards of tropical weather systems.

“Slow-moving or stalled tropical storms or other large rain events” generally pose greater risks in Texas than other hurricane features, said Bill Rich, emergency medicine specialist at the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health. “The rain is more dangerous, in my opinion, than the hurricane wave and wind impacts you see on TV.”

Those in particular jeopardy in slow-moving storms include people like kidney-failure patients who find their dialysis clinics closed when the power goes out or patients who breathe with the help of oxygen concentrators that also depend on electricity.

Hospitals can’t care for patients when the supplies of fuel for their generators runs out or their generators are swamped, as occurred when Allison struck Houston in 2001. Communication can go out as flood waters rise, and resupplies are hampered when trucks can’t get through.

Lack of communication may mean that communities don’t know their water is contaminated or that their clinics and hospitals are closed, said Vivi Siegal, associate director of communications for the environmental health center.

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founder and editor of Texas Climate News. Ruth SoRelle is a TCN contributing editor.