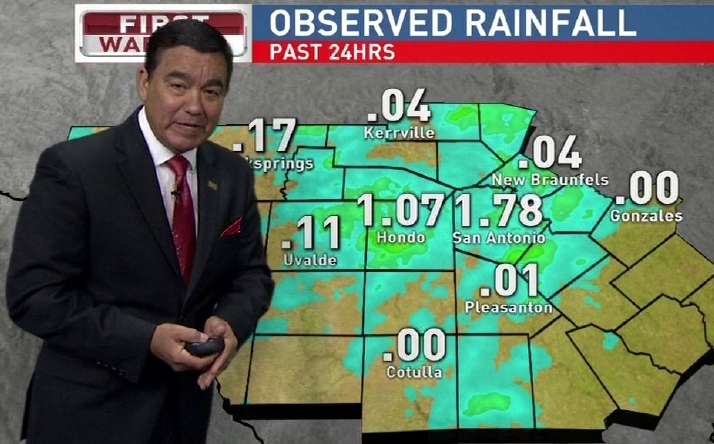

Alex Garcia, chief meteorologist at KABB in San Antonio

By Neil Strassman

Texas Climate News

Shel Winkley was more of a skeptic about global warming and climate change five years ago than today.

Winkley, the 32-year-old chief meteorologist at KBTX television in Bryan-College Station, said forecasting the weather every day makes it easier to see that the climate is changing.

Alex Garcia, 68, chief meteorologist at the KABB television station in San Antonio spotted warming trends as far back as 30 years ago.

“We could see pretty good numbers since ’85,” Garcia said. “After the ’90s, well, you could see the temperature rising.”

Many broadcast meteorologists were once openly doubtful that humans are causing climate change. But their views on that subject are evolving and so is the way they teach the public about climate science in their forecasts.

It is an intimate and trusting connection.

Who else do you invite into your house every morning and night while you may not even be dressed for the day?

Declining skepticism

Academic researchers and the meteorological community have tracked television weather forecasters’ views on climate change through studies that date from 2001 and more recently, through annual surveys.

The most recent survey, published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society last October, shows skepticism among meteorologists continuing to decline and an increasing acceptance of human-caused climate change.

More than 90 percent of weathercasters in the survey recognized that climate change is happening and about 80 percent recognized human-caused climate change is happening.

Slightly more than half say the climate changed in their communities over the last half-century, citing fluctuations in average temperature, heat waves, intensity of rainfall, total precipitation and length of the frost-free season, according to the survey.

About half have noted harmful local impacts on water resources and agriculture and one-third have seen such impacts on human health.

Nearly 60 percent are somewhat interested in reporting on air about possible impacts of climate change and most believe their viewers are at least slightly interested in learning about the local impacts of global climate change.

Many television meteorologists discuss climate change on social media, station websites, blogs, at school visits and in talks to civic and community groups.

“The public’s only daily connection to a scientist is usually their broadcast meteorologist,” said Garcia, who produces in-depth YouTube videos called Beyond the Forecast.

Help for forecasters

The American Meteorological Society, the national professional organization, supports the majority views of its members on climate change.

[See “American Meteorological Society: No more balancing act” below this article]

Climate Central, an independent nonprofit organization of scientists and journalists researching and reporting on climate change and its impact on the public, helps television meteorologists improve their presentations through its Climate Matters program.

“We work with broadcast meteorologists to help them make the weather and climate connection,” said Sean Sublette, a meteorologist with Climate Matters.

Shel Winkley, chief meteorologist at KBTX in Bryan-College Station

Winkley and Garcia use Climate Matters for both research and on-air graphics.

After last year’s February seemed like the warmest ever, Winkley asked Climate Matters to review the last 50 Februarys.

“It’s nice to be able to tie the forecast in locally and be able to say, “Here in College Station,” Winkley said. “I can say here’s the new world we are living in and this is the pattern we are living in.”

Garcia noticed that recent winter cold spells in the San Antonio area seemed to last only a few days instead of a couple of weeks and he asked Climate Matters to dig into the temperature records.

“They take data and they provide data,” Garcia said. The graphics and maps made for television really do help to tell the climate-change story, he said.

In 2016, at the American Meteorological Society’s 44th Conference on Broadcast Meteorology, Garcia moderated a panel on how broadcast meteorologists can convey the science and impacts of climate change.

“Just look around the world”

It is difficult to describe a cause-and-effect relationship between climate change and a single significant weather event like the great storm Hurricane Harvey, last August’s deluge on the Texas coast, the meteorologists say.

“Is Harvey the new normal? You can’t judge it off one storm, but just look around the world at what is happening,” said Winkley.

From San Antonio to North Carolina, weather forecasters talk about the amount of moisture in the air and the above-average warmth of the Caribbean Sea that provides additional fuel to the recent storms.

Studying and conveying climate science seems to have brought a much broader understanding of what goes into the local weather forecast.

“It rains where it shouldn’t and there is drought in new places,” Garcia said. “It doesn’t just involve the atmosphere. It is the oceans, too.”

Both Garcia and Winkley believe that Millennials and folks who are younger are more receptive to science in a forecast and learning about the impacts of climate change.

“It is a bit generational,” Winkley said. “They grew up with the concepts of global warming and climate change and the book [and film], “An Inconvenient Truth.”

Garcia, a former elementary school educator who now teaches college courses, said young people are eager to learn.

“They are ready. They want information,” he said.

American Meteorological Society: No more balancing act

By Neil Strassman

Texas Climate News

Convinced and unconvinced about climate change is the way Keith Seitter, executive director of the American Meteorological Society, framed the debate to his organization’s members eight years ago.

Those days of walking the tightrope are over in the group, whose members include many broadcast meteorologists along with researchers, educators, weather-forecasting enthusiasts and others.

“What’s changed over the last couple of decades is the confidence in the scientific evidence that humans are responsible for warming,” Seitter said in an interview with Texas Climate News. “It’s unequivocal.”

“What’s changed over the last couple of decades is the confidence in the scientific evidence that humans are responsible for warming,” Seitter said in an interview with Texas Climate News. “It’s unequivocal.”

In a Jan. 30 letter to President Trump regarding comments he made belittling climate change in a televised interview two days earlier, Seitter took the president to task for ignoring scientific conclusions from his own executive branch agencies, like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA, and from university researchers.

“Unfortunately, these and other climate-related comments [by Trump] in the interview are not consistent with scientific observations from around the globe, nor with scientific conclusions based on these observations,” he wrote.

There is “credible and scientifically validated information” available to help navigate the difficult policy areas impacted by Earth’s changing climate, Seitter told the president.

Some American Meteorological Society members are not happy with the organization’s stance, Seitter said, but that is the position of the Boston-based group, self-described as “the nation’s premier scientific and professional organization promoting and disseminating information about the atmospheric, oceanic, and hydrologic sciences.”

Seitter said he continues to be frustrated by people who attack the science of climate change rather than seek solutions.

“What do we do in the future? That is where the focus needs to be,” Seitter said. “What are the trade-offs and what needs to be done?”

He is also concerned about the Trump administration’s 2019 budget request that cuts funding for a NASA space observatory and a handful of Earth-science projects.

Funding for some satellites and specialized instruments on orbiting observatories would be cut in the proposed budget.

“If you are trying to figure out what is going on [about climate change] and you take away your eyes, you can’t make progress,” Seitter said.

Some of these observational platforms also help to predict freezing rain and weather forecasts, he said.

+++++

Neil Strassman, an independent journalist in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, is a Texas Climate News contributing editor. Among his past positions in newspaper journalism, broadcasting and local government, he worked for 20 years as an environment, science and political reporter at the Long Beach (California) Press-Telegram and Fort Worth Star-Telegram.